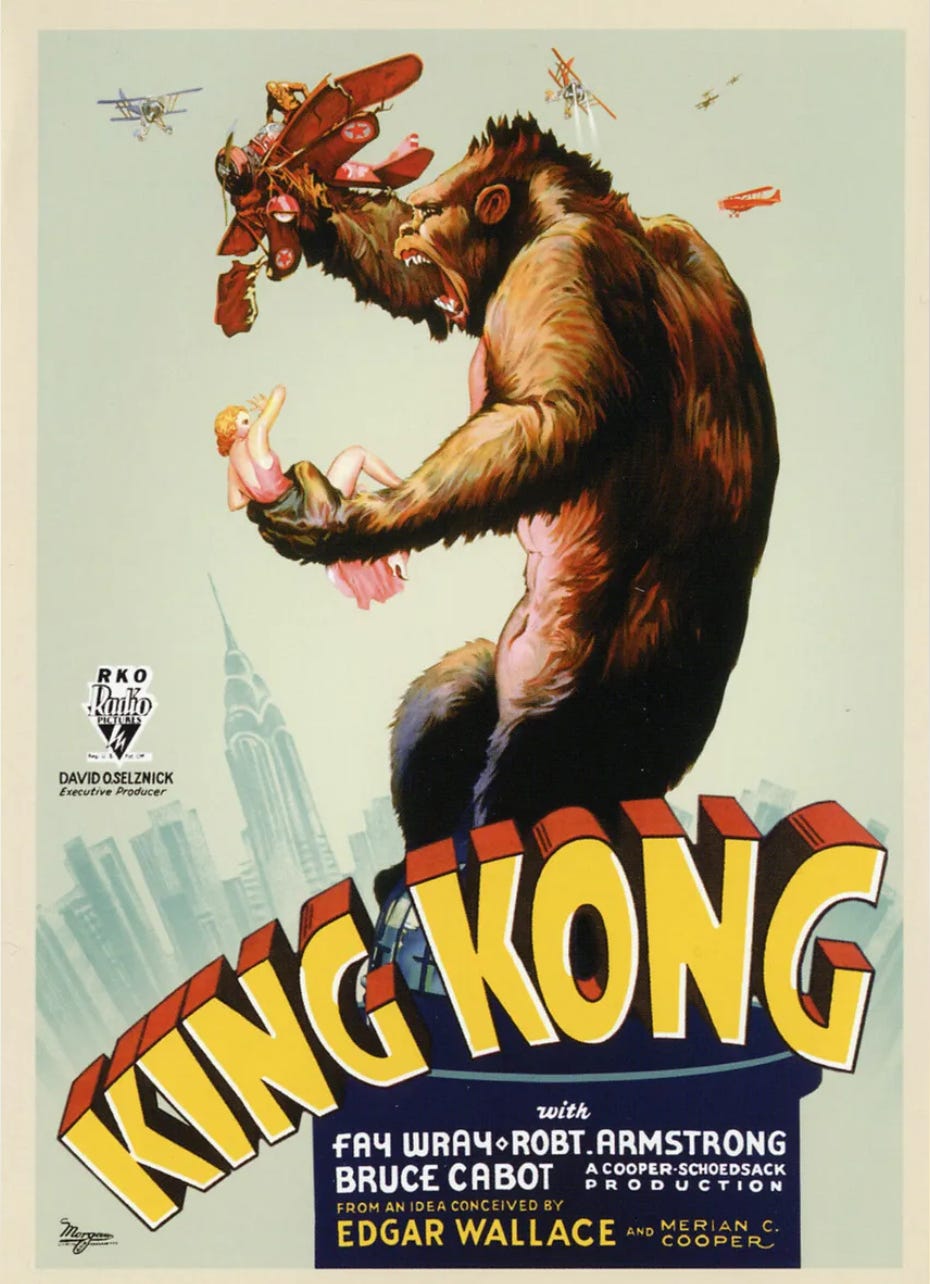

Classic Horror Behind the Scenes: KING KONG Turns 90!

The venerable fantasy/monster movie has been captivating audiences for years. But the stories regarding the people who made the film are just as fascinating…and, sometimes, just as tragic.

By Bill Fleck, author of the Rondo Classic Horror Awards-nominated CHANEY’S BABY, available here.

I was begrudgingly painting the front of my house last week, and as I reluctantly ascended the extension ladder, I hummed some of the background music from KING KONG (1933).

As I always do.

You know, Max Steiner’s magnificent score as Kong climbs the Empire State Building.

I laughed, and found my thoughts drifting back to the first time I encountered the film.

How many years ago? Well, I was in third grade, so more than fifty. One afternoon, I found myself idly twisting the dial on the Fleck family TV in the living room in search of something decent to quell my boredom.

Suddenly, the image of a giant gorilla prowling around high on a cliff caught my eye. I don’t know how, but I just knew this was KING KONG.

[Above: Though this image does not appear in KING KONG per se, Kong prowling around on Skull Mountain was my first exposure to him.]

To this day, I can’t explain if-and-when I’d been made aware of the film. Had my dad mentioned it? Had I seen a poster somewhere? Had Kong come to me in a dream? Honestly, I don’t know. But I just knew this was KING KONG.

“Mom?” I called to my mother who was working in the kitchen. “Can I watch KING KONG?”

There was an ominous pause before she answered.

“Alright,” came the reluctant reply. “But I don’t want you drawing any pictures of it!”

I guess I couldn’t blame her for making that stipulation. I’d recently seen ABBOTT AND COSTELLO MEET FRANKENSTEIN (1948), and my teacher sternly reported that my school work had suffered while I cranked out endless action portraits of The Wolf Man. [1]

“Okay!” I agreed…although, of course, I knew I wouldn’t comply.

I’d obviously missed a lot of the film by the time I’d accidentally stumbled across it. But I still got to see Kong’s battle with a pterodactyl.

And his deadly rampage through a native village.

His capture and eventual exploitation in New York City.

His escape and destructive antics in the city.

And finally, his triumphant—but ultimately tragic—climb up the Empire State Building…accompanied by the distinct music that I now hum going up a ladder.

I’m not going to lie—I cried when he died.

It was probably a year or more after that when I finally got to see the entire film [2]—back then, we were at the mercy of TV stations randomly deciding to air our obsessions.

Well, my fourth-grade self was fascinated by the build-up.

By Carl Denham.

And, of course, I fell in love with Fay Wray…and I was jealous as all get-out of Jack Driscoll!

But, of course, Kong was the star. I still consider his epic battle against the Tyrannosaurus Rex [3] to be among the single most awe-inspiring action sequences ever made.

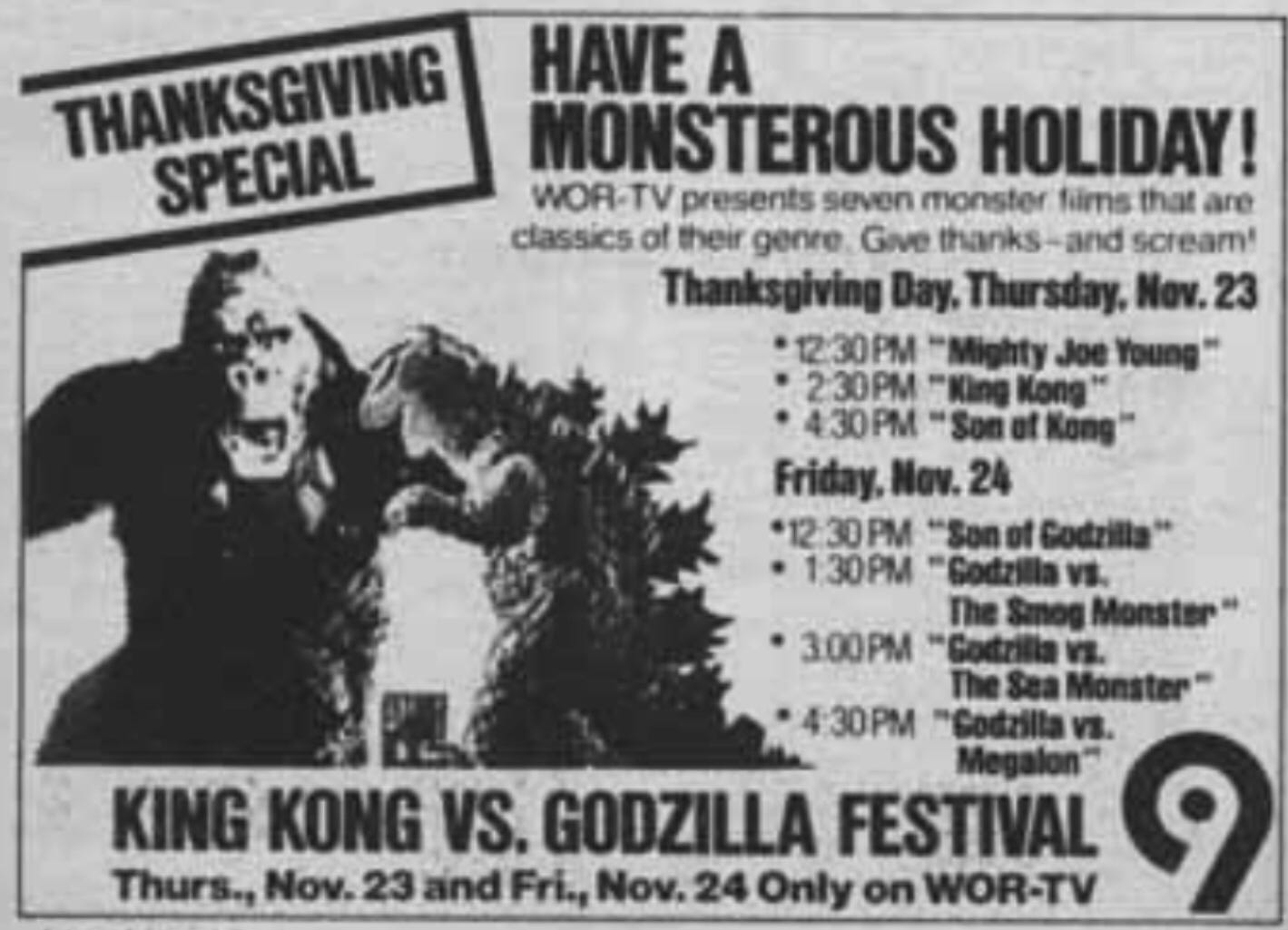

Since then—thanks to yearly Thanksgiving runs on TV, The Nostalgia Merchant Super-8 release, the advent of cable, Betamax, VHS, DVD, Blu-Ray, showing it twice a year in my high school Cinema elective class, and streaming—I’m sure I’ve seen KING KONG more than one-hundred times. [4]

[Above: KING KONG was a staple on Thanksgiving Day on TV for years when I was a kid. And I’d be lying if I didn’t admit that it was more important to me than was the turkey dinner.]

Of course, like anything else that’s 90-years old, KING KONG has some springs that hang out.

To begin with, Kong’s first appearance—in spite of expert lighting, a clever combination of miniatures with live action, and Steiner’s blaring brass—is a bit of a letdown thanks to the ‘jerks’ inherent in stop-motion animation.

“He looks like a cartoon,” my students would often comment. [5]

Then, too, the film is justifiably famous for its rapid pace and unrelenting action. But, in retrospect, it leaves me wondering—Does this kind of stuff happen every day to Kong? Or did we just happen to catch him at a time when everything goes haywire? [6]

And, of course, there are certain racial stereotypes and misogynist behaviors that were par for the course back in 1933, but certainly—and justifiably—raised concerns in classroom discussion eighty-odd years later.

That said, KING KONG is still a triumph of filmmaking and a testament to the creative geniuses behind it, including producer Merian C. Cooper, producer/director Ernest B. Schoedsack, screenwriter Ruth Rose, composer Max Steiner, and special effects genius Willis H. O’Brien.

Over the years, I’ve learned a great deal about KING KONG—the people who made it, how they did so, and what the film meant for their careers.

So, as KING KONG turns 90, here are some of those stories…

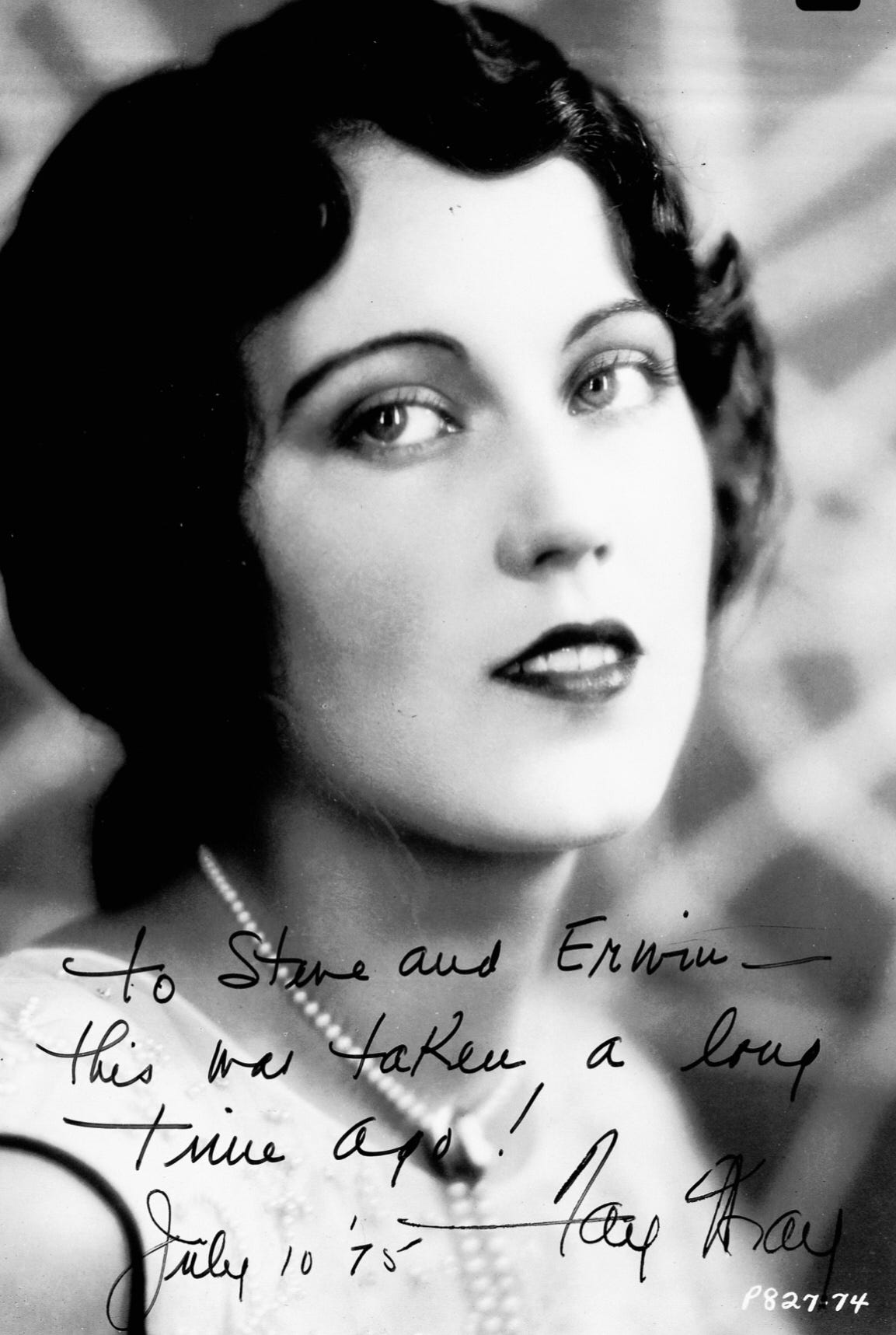

Fay Wray Disliked Horror Films

“Some of those were a little too gruesome. I wasn’t too comfortable all the time in those. I didn’t really care for them.” –Fay Wray

[Above: Actress Fay Wray, pictured with her naturally dark auburn hair. Thanks to KING KONG, the world would think of her as a blonde.]

June 1932. Actress Fay Wray is running ragged at RKO studios.

By night, with her natural dark auburn hair, she’s being chased furiously through the rugged jungle set by the crazed Cossack manhunter Count Zaroff, played with flair by British actor Leslie Banks. The film is THE MOST DANGEROUS GAME.

[Above: Fay Wray in THE MOST DANGEROUS GAME (1932), shot at the same time as KING KONG on many of the same sets.]

By day, in a flowing blonde wig, she’s being chased furiously through the same sets by a giant gorilla named Kong, who will be (mostly) played with flair by an 18-inch model built by Marcel Delgado, and animated by Willis O’Brien. The film, of course, is KING KONG.

The blue-eyed, 24-year-old actress has been married to screenwriter John Monk Saunders (1927’s WINGS) for more than three years [7]. And she’s becoming no stranger to screen screams. [8] She’s already been menaced in DOCTOR X (1932), and will soon face off against Lionel Atwill in MYSTERY OF THE WAX MUSEUM as well as THE VAMPIRE BAT (both 1933).

This is certainly not the direction the Canadian-born, Mormon-raised Fay envisioned her career unfolding. After all, her favorite of the films she’s done so far is Erich von Stroheim’s THE WEDDING MARCH (1928).

She wasn’t even sure what KONG would entail when producer/director Merian C. Cooper—who had starred her in THE FOUR FEATHERS (1929), and whom she knows is something of a practical joker—first approached her.

“Mr. Cooper said to me that he had an idea for a film in mind. The only thing he’d tell me was that I was going to have the tallest, darkest leading man in Hollywood. Naturally, I thought of Clark Gable.” [9]

Instead, Cooper whips out sketches of Kong.

“My heart stopped, then sank…” she recalls later. “Cooper was delighted at my amazement, especially, I think, at the look of shock and apprehension on my face.”

To make matters more interesting, she has to pretend King is on set for most of the shoot.

“Sometimes I worked with just a background of a rock or a tree or black velvet, and just had to imagine the whole thing,” she explained.

Sure, Delgado has built some life-sized props…

There is a spectacular bust of Kong, made from rubber and wood, which features glass eyes and is covered in bear skin. Three technicians can fit inside, and—using a variety of levers and compressors—they create a wide range of expressions…

Then, there is a huge Kong foot which is used to step on his unfortunate victims…

There is Kong’s ramrod-like right hand, used to menace actor Bruce Cabot as Driscoll while he hides from Kong in a shallow cave…

But most importantly, there is Kong’s articulated right hand, which is built over a steel bar so that it can hold Wray.

[Above: (1) Special effects artist Willis O’Brien and producer/director Merian C. Cooper stand in front of the life-sized bust of Kong; (2) Brothers Marcel and Victor Delgado work on the articulated hand that will hold actress Fay Wray in the film.]

The resilient actress spends a lot of time in that hand, high in the air above the soundstage, the lever-powered fingers pressed around her body, a wind machine blowing her clothes. At times, thanks to the writhing of her character (Ann Darrow), Kong’s fingers begin to loosen…and she grips desperately at his wrist.

“Actually,” she’ll write years later, “the fear about falling out of the hand was a match for the imagined fear it would have been to be looking up at Kong himself.”

When gravity comes too close, the actress calls out to the techs for help.

“They were very considerate, I must say,” she comments later. “Every time I felt I was about to slip out of these fingers and would yell for help, they’d let me down and re-organize things.”

Since the film is shot over a period of about ten months, Wray and the rest of the cast are hired and laid off in shifts. When not working, they’re not getting paid, so the actress makes several other pictures in the interim.

Still, her experience performing in KONG is one she’ll fondly remember.

“Both of these men, Cooper and Schoedsack, gave me absolute freedom to make my own choices, and never made me feel that I was being directed,” she’ll explain. “There were often scenes that were done in one take.”

March 2, 1933. KING KONG opens in New York. It’s an immediate sensation, and the profits save RKO from bankruptcy.

Of course, Kong himself gets the most attention—he’s been brought brilliantly to life by special effects guru O’Brien and his merry band of animators, not to mention the amazing sound effects by Murray Spivack. [10]

But Wray gets the most attention of the live actors, and rightfully so. She will be associated with the film for the rest of her life.

However, when her streak of five horror flicks in a row comes to an end, she’s incredibly grateful.

“All she has to do in THE WOMAN I STOLE, showing today and Friday at the Fox theater…is be unfaithful to her husband,” The Californian notes on June 29, 1933.

“And what a relief it is…” Wray says. “And that is not a difficult thing to do after meeting monsters, mad men, octopi, and apes.” [11]

In her later years, Wray is able to make peace with her reputation as a Scream Queen. Unfailingly polite and charming, she embraces the fact that she will always be remembered for KONG with zeal.

“When I’m in New York,” she writes in 1989, “I look at the Empire State Building and feel as though it belongs to me ... or is it vice versa?”

Fay Wray died on August 8, 2004 at the ripe old age of 96.

Of course—like Kong—she died in New York.

[Above: Kong climbing the Empire State Building is one of the most iconic images in cinema history. Fay Wray often felt like she owned the building…and deservedly so.]

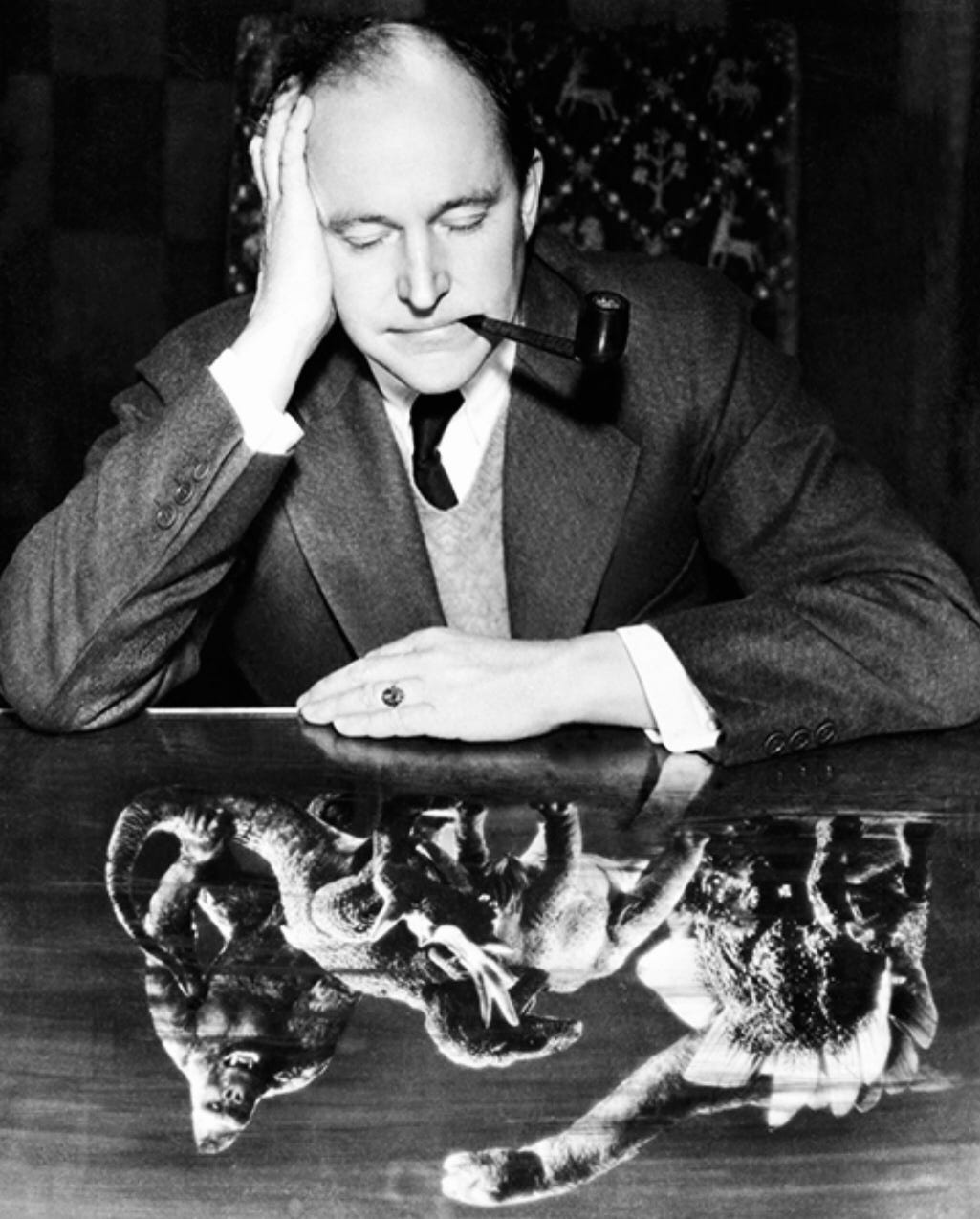

“I want…the fiercest, most brutal, monstrous damned thing that has ever been seen!”

Spring, 1932. Marcel Delgado finds himself between a rock and a hard place.

On his left, the rock: producer/director Merian C. Cooper, 39—five-eight, with a muscular build.

Nickname: Coop.

A fireball of energy with his mouth perennially stuffed with a pipe or his beloved cheese and crackers.

A combat pilot.

A former P.O.W.

A world traveler who—with his film partner Ernest B. Schoedsack—has made unique, natural-life pictures in some of the most dangerous places on the planet.

The inspiration for Carl Denham.

A politically conservative teetotaler.

(This only scratches the surface…)

On Delgado’s right, the hard place: Willis Harold O’Brien, 46.

Nickname: Obie.

One of three sons…his father, William, served as assistant city attorney in Oakland, CA, for fifteen years.

A former rancher, cowboy, fur trapper, boxer, and bartender.

A “man with a strong will and a thirst for adventure,” as described by writer Graham Edwards.

A pioneer in the art form that is three-dimensional animation, his biggest smash to date being THE LOST WORLD (1925).

The man who talked Delgado into working with him as a model-maker.

The issue dividing Cooper and Obie?

The physical appearance of Kong.

Delgado is 31. Born in Coahuila, Mexico, he’s lived in California since 1910. He meets Obie while taking art classes—Obie is attempting to step up his model-making for THE LOST WORLD at First National.

Impressed by Delgado’s work, Obie offers the younger man a job. Marcel turns him down…at first.

Then, one Saturday, Obie talks Marcel into visiting him at the studio. He shows Marcel a dedicated work space he’s set up.

“How do you like your studio?” Obie asks.

“What do you mean?”

“Well, this is your studio if you like it,” Obie explains. “If you want it, it’s yours.”

Delgado is blown away.

“Thanks,” he manages.

There’s an awkward pause.

“When are you going to start work?” Obie finally asks.

“Right now.”

His job? To make dinosaurs.

“I didn’t know just where to begin,” he recalled years later. “I just started.”

Using noted paleo-artist Charles R. Knight’s paintings as a guide, Delgado crafts realistic miniature prehistoric creatures out of metal, foam rubber, and liquid latex.

The results on screen are spectacular.

[Special effects pioneer Willis H. O’Brien animates prehistoric creatures constructed by Marcel Delgado in THE LOST WORLD (1925).]

And now, eight years later, Coop wants the Delgado treatment for his giant gorilla.

Kong is Cooper’s brainchild—several years earlier, he’d awakened from a dream and jotted it down: a giant gorilla terrorizes New York. He’d originally toyed with the idea of having a real gorilla battle Komodo dragons, but has since determined the plan is impractical.

[Above: Producer/director Merian C. Cooper, depicted in split screen dreaming up the concept for KING KONG.]

But test scenes for an RKO production called CREATION—featuring dinosaurs by Delgado and animated by Obie—fire his imagination.

Can he make his Kong picture this way?

He decides to find out. But he needs dynamite test reels to impress the suits in New York.

He cancels CREATION, which he describes as “a bunch of animals walking around.”

Obie and Delgado are crushed…at first.

But then, Coop meets with them and explains the concept for Kong. Do Obie and Delgado think they can pull it off?

Can they pull it off? Oh, absolutely!

Coop’s order is in:

Make a gorilla that will look as big as a dinosaur.

But after Coop leaves, Obie has another order:

“Make the ape almost human.”

Delgado follows Obie’s instructions. According to THE MAKING OF KING KONG, Delgado “designed a monstrosity combining the features of man and ape.”

The reveal does not go well.

“That’s the funniest-looking thing I’ve ever seen!” Coop explodes. “It looks like a cross between a monkey and a man with long hair. Damn it, I want to put a pure gorilla on that screen!”

Delgado goes back to the drawing board. His second effort looks more like an ape, but still features some very obvious human characteristics.

Again, Coop isn’t on board.

“I want…the fiercest, most brutal, monstrous damned thing that has ever been seen!” he insists.

“It’s going to be impossible to win over an audience with a monstrous ape lacking in human qualities,” Obie counters.

Coop is unmoved.

“I’ll have women crying over him before I’m through,” he declares, “and the more brutal he is, the more they’ll cry at the end.”

And so, for Delgado, it’s “rock, meet hard place.”

In the end, of course, Coop will win. After all, he is executive assistant to RKO V.P. David O. Selznick. And he controls the money.

Determined to get what he wants, Coop calls the American Museum of Natural History in New York. He asks for the exact dimensions of a bull gorilla.

He passes these on to Delgado, who constructs two Kongs.

And the Legend is born.

[Above: One of the two 18-inch models Delgado constructed of Kong. The models would deteriorate constantly, and Delgado often found himself stripping them down to the metal skeleton…only to build them back up again so shooting could proceed.]

“Under High Nervous Tension.”

This is a sad one. Be prepared.

It’s October of 1933. KING KONG is a major hit, and Willis H. O’Brien is a big reason for that. There will even be talk of awarding him an Oscar—talk he squelches himself when the Academy refuses to give everyone on his team a statuette.

He should be on top of the world.

But KONG’s success has put an unforeseen millstone around his neck: a sequel, called SON OF KONG.

This should be good news. But then, the budget is announced: $250,000. This is about a third of the budget for KING KONG.

Then, Obie hears the plot. He doesn’t like it at all. It dawns on him that RKO is rushing this one through on the cheap to mop up any spare bucks KONG may have left behind.

It doesn’t help that his salary is stalemated at $300 per week—roughly $7000 when adjusted for inflation at this writing. Good coin—especially in Depression-torn America—but don’t his contributions to RKO’s recent box office blockbuster warrant a raise?

[Above: SON OF KONG. In the opinion of Willis O’Brien, the film was a pathetic rush-job, cynically designed to mop up any bucks KING KONG had left behind.]

“O’Brien wasn’t a businessman,” Marcel Delgado will lament years later. “He was just a good, fine artist, and he knew what he was doing. But as far as having business ability, he didn’t have it.”

Unfortunately, even Obie’s undeniable artistic powers are being crowded on SON.

First, the budget will not allow for the spectacular prehistoric animal stampede at the climax that Obie has planned. This hurts.

Then, there’s Coop and Schoedsack. Both have always been forceful and opinionated, but on KONG, they pretty much left Obie alone to get done what they wanted.

But now, they’re acting like they’re special effects artists themselves. As such, they get under Obie’s skin by making suggestions regarding exactly how he should go about his work.

“[E]normous debates arose over matters that would formerly [have] been resolved simply and autonomously,” John Michlig will write for FAMOUS MONSTERS in 2013.

None of this is pleasant. Obie begins to withdraw. [12] He leaves most of the animation to Buzz Gibson, his assistant.

Sadly, as bad as things are for Obie on the set, it’s nothing compared to what’s happening in his private life.

It begins with Obie’s impulsive nature. After all, this is the guy who left home at the age of 11 to work on a cattle ranch.

Equally impulsive is his 1917 marriage to Hazel Ruth Collette.

[Above: Hazel Ruth Collette O’Brien, whom Willis O’Brien married c. 1917. Their story would end in tragedy.]

Hazel is 19 when she marries the 31-year-old Obie. According to Michlig, Hazel has a manipulative aunt who “fairly trapped” O’Brien into getting engaged.

“The marriage seemed doomed from the beginning,” Michlig observes. “Obie felt snared.”

Then there is Hazel herself, who is very much prone to major mood swings. According to Obie’s brothers, Douglas and Meredith, Hazel is “erratic.”

When Delgado first meets Hazel at the time of THE LOST WORLD, he observes that she seems to be constantly “under high nervous tension.”

Still, the couple has two sons—William, born in 1919, and Willis Jr., born in 1920. But when THE LOST WORLD improves Obie’s financial lot, he acts out in what Michlig terms “the cad troika: booze, the racetrack, and other women.”

By 1930, Hazel and Obie are separated. She retains custody of their sons, but Obie is still a major presence in their lives.

It’s a good thing he is.

By 1931, Hazel is suffering from both tuberculosis and cancer. She takes narcotics to numb the pain.

A lot of narcotics.

Then, William develops tuberculosis in both eyes. He’s blinded as a result.

Both parents are devastated, of course, but Obie continues to take the boys on outings…including football games, where Willis provides play-by-play commentary for William.

One such outing includes a visit to the SON OF KONG set, where William enjoys handling Delgado’s dinosaurs…even if he can’t see them.

When Obie drops them off at their home in Westwood Hills, he has a brief conversation with Hazel. She tells him that she’s thinking about studying the law to “occupy her mind.”

Willis O’Brien is mercifully unaware of what’s to come.

Saturday, October 7, 1933. Early morning. William is asleep in the front bedroom, and Willis Jr. is sacking on the sleeping porch.

But Hazel O’Brien is awake in her room.

Her mind is spinning. She can’t sleep. And there’s no one to leave the kids with.

What she does next is horrifying.

She takes a loaded .38-caliber pistol to William’s room and shoots her son twice in the chest.

The shots wake Willis up. By the time Hazel gets to him, he struggles with her and she has to fight him off.

Then she shoots him in the head. [13]

She makes her way back to her bedroom. There, intending to die herself, she shoots herself in the chest.

Meanwhile, the unmistakable sound of bullets being fired has aroused the neighbors. They make panicked calls to the police. When the cops arrive, they survey the tragic scene…and discover that Hazel is still alive. She’s rushed to Santa Monica Hospital.

When she’s able, she spills everything through agonized breaths.

“My husband is not to blame in any way,” she chokes out. “I just couldn’t sleep, and there was no one to leave the kids with.”

Informed of the tragedy, Obie bursts out in tears.

“This is the last thing I ever expected,” he says. “I saw my wife and the boys yesterday afternoon. She was in high spirits.”

What could possibly have motivated her to do such a thing? he’s asked.

“The only thing I can say is that I think she did it because of her illness,” Obie speculates. “She was very morbid at times. She always brooded because the older boy was blind, and because she thought the children would not get good care. But I always took good care of them.”

[Above: Sadly, the headlines say it all. And the life of Willis H. O’Brien is changed forever.]

Back at the hospital, Hazel is informed that there’s a slight chance she might live. [14]

“That’s the last thing in the world I want!” she exclaims.

As a result, she embarks on a hunger strike.

“I don’t want to live,” she declares to the press, “but I couldn’t go without my boys.”

She’s charged with murder. Her day in court is postponed until her health improves. She’s attended to in the prison ward of Los Angeles General Hospital. Later, she’s transferred to the Los Encinos Sanitarium near San Francisco.

She begins telling the authorities that she and her sons were “afflicted with an incurable ailment,” and that she wanted all three of them to die together.

October 12, 1933. Services for William and Willis O’Brien, Jr. are held at the Little Church of the Flowers, Forest Lawn Memorial Park. A devastated Obie watches as his sons are interred.

Shortly thereafter, a jaded Obie returns to work on SON OF KONG. A misguided photographer snaps a portrait of the grieving father at work. When he’s presented with a print, he tears it to shreds. [15]

Perhaps the pain he sees in his own eyes is too much for him?

[Above: A clueless photographer shoots a picture of a grieving Obie shortly after his sons have been buried. Presented with the print, Obie tears it up. His friend Marcel Delgado tapes it back together. At this writing, it is incorrectly described on Wikipedia as having been shot in 1931.]

November 16, 1934. Hazel O’Brien is dead.

“Death has defeated the law in the case of Mrs. Hazel Ruth O’Brien, brooding mother who killed her two sons and then tried to kill herself,” the AP reports.

Though she’s managed to live more than a year after shooting herself, she’s never been to court. [16]

And Obie has never visited her.

The very next day, Obie marries his girlfriend Darlyne Prenett. The ensuing 28 years will be a rollercoaster for the couple.

O’Brien will passionately propose projects that never get off the ground.

Money will forever be an issue.

The projects he is offered are often subpar.

But he’ll win an Oscar for MIGHTY JOE YOUNG (1949), and his marriage to Darlyne will be a happy one, lasting until his death on November 8, 1962 at the age of 76.

Today, among fans in the know, he’s justifiably honored as a pioneering special effects genius.

But he should also be honored as the survivor of one of the most terrible occurrences we human beings can imagine.

[Above: Obie earned an Oscar for his work on the Cooper-Schoedsack production of MIGHTY JOE YOUNG (1949).]

“He was like his name—Noble.”

February 18, 1915. D.W. Griffith’s THE BIRTH OF A NATION is released. It will eventually sweep the country, and earn more money than any other film up to that time.

It will also deeply—and justifiably—anger Black Americans thanks to its blatantly racist treatment of their ancestors.

One of these is Noble Mark Johnson.

And he will do something about it.

[Above: Noble Mark Johnson, actor and activist. He is often cited as being the first Black American star in motion pictures.]

Johnson is born in Marshall, Missouri on April 18, 1881. His family soon moves to Colorado Springs, Colorado. Noble’s dad becomes an in-demand horse trainer.

At school, Noble meets up with Leonidas Frank “Lon” Chaney. They become fast friends—a relationship that will be renewed when they both eventually end up working in Hollywood.

Meanwhile, Noble leaves school to work with his father.

Legend has it that Johnson scores his first acting role in his mid-thirties. [17] As the story goes, he’s working with horses on a film set when an actor playing a Native American gets sick and can’t go on. The powers-that-be shoot around worried glances, and happily notice the six-two, powerfully-muscled, lightly-complected trainer. They cast him on the spot.

If true, it’s certainly not the last time Johnson will portray a Native American. As writer Cassandra Geraghty notes, “Although African-American, his ambiguously light complexion allowed him to play a wide variety of roles and ethnicities (including Native American, Arabian, Asian, and other ‘exotic’ types) as a character actor.”

Johnson’s involvement in acting is a joy to him…except for the fact that the film industry isn’t inclined to produce films that properly represent Black culture. THE BIRTH OF A NATION is the most obvious—but certainly not the only—proof of that.

So, with the help of his brother—newspaper writer George Perry Johnson—and fellow thespian Clarence Brooks, Noble puts together the Lincoln Motion Picture Company in Omaha, Nebraska.

The mission? To make authentic, relevant films for Black audiences. Johnson is in charge, and the movies will be shown in schools and churches as well as movie theaters.

“He was like his name—Noble,” fellow KING KONG alumni Bruce Cabot will astutely comment later.

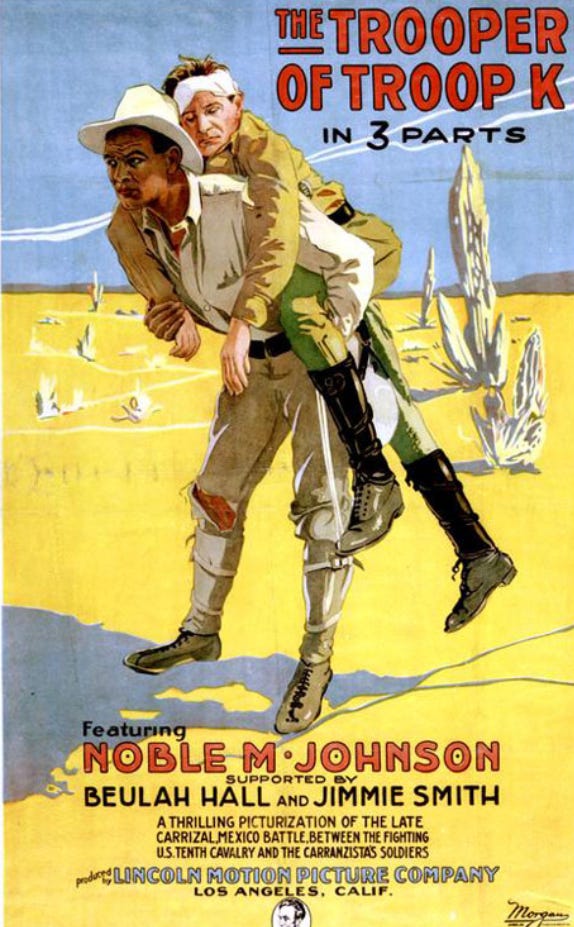

[Above: Noble Johnson founded the Lincoln Motion Picture Company to make films that depicted the authentic Black American experience.]

Johnson himself stars in the first three Lincoln offerings: THE REALIZATION OF A NEGRO’S AMBITION (1916)—described by a reviewer as “the business and social life of the Negro as it really is and not as our jealous contemporaries would have us appear”—THE TROOPER OF TROOP K (1916), and THE LAW OF NATURE (1917).

The films gain traction, and two are shown at the Tuskegee Institute in 1917. “[S]uch pictures as these are not only elevating and inspiring in themselves,” the Tuskegee Student points out, “but they are also calculated to instill principles of race pride and loyalty in the minds of colored people.”

Not only are the movies successful; Johnson himself becomes very popular. So, in addition to his work at Lincoln, he acts in films for other production companies as well, often pouring his salary back into his own company.

[Above: The Lincoln films made Johnson a very popular performer. Unfortunately, Universal Pictures saw Lincoln as a competitor, and forced Johnson to choose sides…]

Unfortunately, the situation is untenable for Universal Pictures, where Johnson is up for a contract. Fearing that splitting time between ventures would prove impossible—and disliking the competition the Lincoln Project represents—Universal demands the following:

1. Johnson must cut ties with Lincoln.

2. Lincoln must not use Johnson’s name or likeness in any new publicity, and any old publicity is not to be repurposed.

Johnson—no doubt agonized over having to make such an unreasonable choice—reluctantly sides with Universal. On September 3, 1918, Noble tenders his resignation from Lincoln, and Universal’s selfish demands are read into the record. [18]

As painful as this incident must be, Johnson’s career flourishes in Hollywood. He works in productions with Rudolph Valentino and Douglas Fairbanks (among others), and makes the transition from The Silent Era to Talkies look easy.

It’s at the beginning of the Talkie-era that he lands the roles he’s most remembered for today: Janos, the Black One in MURDERS OF THE RUE MORGUE (1932), Ivan in RKO’s THE MOST DANGEROUS GAME (1932), The Nubian—opposite Boris Karloff—in THE MUMMY (1932), and—of course—the Native Chief in both KING KONG and SON OF KONG (1933).

[Above: Noble Johnson in the roles for which—rightly or wrongly—he is best remembered for today: (1) Janos in MURDERS IN THE RUE MORGUE; (1932) (2) Ivan in THE MOST DANGEROUS GAME (1932); (3) The Nubian in THE MUMMY (1932); and (4) The Native Chief in KING KONG/SON OF KONG (1933).]

A soft-spoken gentle giant in real life, Johnson remained an in-demand character actor for years, making notable appearances in films like SHE WORE A YELLOW RIBBON (1949) for John Ford, opposite the likes of John Wayne. He essayed his last big-screen appearance in 1950, and—save for a brief role in a TV film called LOST ISLAND OF KIOGA in the 1960s—retired from performing to invest in properties in Nevada.

In all, he made nearly 150 pictures.

[Above: Johnson in one of his last big-screen pictures, John Ford’s SHE WORE A YELLOW RIBBON (1949). Johnson was often mistaken for a Native American in real life.]

Noble Johnson eventually moved to Yucaipa, California, and lived quietly until dying there at the age of 96—just like Fay Wray!—on January 9, 1978.

Along the way, he must have noted milestones like Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the Civil Rights movement, the Voting Rights Act (1965), the assassination of Malcolm X (1965), and the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. (1968). If he made any comments about any of it, they must have been private.

But—as his founding of the Lincoln Motion Picture Company demonstrates—Noble Johnson was a man of action, not of words.

[PS: Rondo-winning director Thomas Hamilton (BORIS KARLOFF: THE MAN BEHIND THE MONSTER) is seeking funds to make THE CHANEYS: HOLLYWOOD’S HORROR DYNASTY. Follow this link to see more about the project, and possibly make a donation: (click here).]

Notes

[1] Billed as “The Wolfman” in the film.

[2] Or, the entire film as it was before the notorious “cut” scenes were restored…not to mention the edit for TV so commercials could be fit in.

[3] Some insist that Kong fights an Allosaurus, citing the three digits on its forelegs. Cooper himself said the same thing (see Vaz, p. 216). Feel free to pick your favorite.

[4] I had the dialogue memorized as well, and often muttered the entire film to myself while dusting shelves at the community drug store where I worked starting at age 15.

[5] Of course, many of the same ones would be saying, “Oh, no—don’t kill him!” at the end.

[6] This is where I fault Peter Jackson’s remake in 2005. At three hours, it gave me time to think…something you shouldn’t really do while watching a Kong film.

[7] Saunders—though brilliant—is an unpredictable drinker and substance abuser. He and Wray separate in 1938 and divorce in December of 1939. Wray is awarded custody of their 3-year-old daughter, Susan Cary. Sadly, roughly three months later, Saunders hangs himself.

[8] That famous scream of hers will come in handy in real life on June 20, 1933 when the actress almost drowns while swimming in Plaza Del Ray. Caught in a riptide, Wray is about to be dragged out to sea when her screams alert director George Hill (1931’s THE SECRET SIX). Hill jumps into the water and gets Wray to safety minutes before lifeguards arrive.

[9] In other interviews over the years—and in her autobiography—she mentioned Cary Grant instead.

[10] Though it must be noted that, at least for me, it’s annoying that all of the screaming sailors in the film have the same voice—Spivack’s.

[11] The “octopi” she refers to is a reference to BELOW THE SEA (1933), in which her character is trapped in a deep-sea diving bell and menaced by a giant octopus.

[12] “Can there be any doubt why Denham bandages lil’ Kong’s middle finger in the film?” Michlig writes.

[13] According to Michlig, Willis barely survived the initial attack but died while being transported to the hospital.

[14] “In a cruel twist of fate,” Michlig writes, “Hazel’s self-inflicted bullet not only failed to kill her, but it actually drained her tubercular lung and extended her life.”

[15] Marcel Delgado retrieves the pieces and tapes them back together. The patched-up photo is eventually reproduced in THE MAKING OF KING KONG.

[16] Her case was set to begin on January 7, 1935.

[17] The story is alleged to have occurred in 1915, which would have made Johnson about 34. Interestingly, Johnson was often mistaken for a Native American in real life. The authors of THE MAKING OF KING KONG assert, “Johnson was technically a mulatto,” but I can’t find any evidence to support this.

[18] Noble’s brother George takes charge. Though the company had moved to California, George tries to run it from Nevada (where he has a day job as a U.S. Postmaster). Sadly, Lincoln produces only two more pictures. It folds in 1922.

Sources

“Divorce Won by Fay Wray.” THE LOS ANGELES TIMES. December 13, 1939, p. 27. Print.

Edwards, Graham. “Revisiting Cinefex (7): Willis O’Brien.

https://www.graham-edwards.com

. Web.

Fay Wray. (n.d.). AZQuotes.com. Retrieved March 20, 2023, from AZQuotes.com Web site: https://www.azquotes.com/author/15954-Fay_Wray

“Fay Wray Ends ‘Horror’ Role.” THE CALIFORNIAN. June 29, 1933, p. 10. Print.

“Fay Wray Saved from Drowning by Director.” THE SACRAMENTO BEE. June 21, 1933, p. 7. Print.

“Fay Wray Sobs as Tribute is Paid John Monk Saunders.” THE LOS ANGELES TIMES. March 17, 1940, p. 3. Print.

“Fay Wray Sobs Aloud at Saunders’ Funeral.” FORTH WORTH STAR-TELEGRAM. March 18, 1940, p. 7. Print.

“Film Man’s Wife Kills Two Sons, Shoots Self.” THE SACRAMENTO BEE. October 7, 1933, p. 1. Print.

Geraghty, Cassandra. “Noble Johnson: A Man Whose Body of Work is More Famous Than His Name.” NORMAN STUDIOS. July 20, 2020.

https://www.normanstudios.org

. Web.

Interview with Marcel Delgado. JIM LANE’S CINEDROME. https://jimlanescinedrome.com/series/marcel-delgado. Web.

Lupack, Barbara Tepa. “Noble and George Johnson: The Lincoln Motion Picture Company. NORMAN STUDIOS. 2023.

https://www.normanstudios.org

. Web.

KING KONG (1933). AFI CATALOG. catalog.afi.com. Web.

Michlig, John. “Every Picture Tells a Story.” FAMOUS MONSTERS OF FILMLAND. May/June 2013. Print.

MOST DANGEROUS GAME, THE (1933). AFI CATALOG. catalog.afi.com. Web.

“Mother Kills Two Sleeping Boys, Tries to End Own Life.” OAKLAND TRIBUNE. October 7, 1933, p. 2. Print.

“Slayer of Young Sons Improving.” THE LOS ANGELES TIMES. October 12, 1933, p. 7. Print.

“Trial Set, But Slayer Dies.” THE SAN FRANCISCO EXAMINER. November 20, 1934, p. 19. Print.

Turner, George E., Dr. Orville Goldner, and Michael H. Price. THE MAKING OF KING KONG. Pulp Hero Press, 2018. Ebook.

Vaz, Mark Cotta. LIVING DANGERUSLY: THE ADVENTURES OF MERIAN C. COOPER. New York: Villard, 2005. Print.

“Woman Who Killed Sons May Recover.” IMPERIAL VALLEY PRESS. October 9, 1933, p. 1. Print.

Wray, Fay. ON THE OTHER HAND. St. Martin’s Press, 1989. Print.

The pictures utilized herein are for educational purposes only. I do not own the copyrights.

Outstanding article with a ton of excellent information. Many things to learn here. Thank you!

I’m was digging the heck out of your piece when I suddenly saw my name!

Honest -- I was ready to recommend it even before your thoughtful attribution. Great stuff! You have a new fan.