Classic Horror Behind the Scenes: Monster Kid Trivia

Some trivia items designed to make you say, “What?” or “Wow!”

By Bill Fleck, author of the Rondo-nominated nonfiction book CHANEY’S BABY, available here.

(Check out the other articles on this Rondo-nominated website! You can access the homepage here.)

I’ve been a Monster Kid since I first saw ABBOTT AND COSTELLO MEET FRANKENSTEIN when I was in third grade. That’s fifty-two or fifty-three years ago. (I know what some of you are thinking: “Fleck, you’re just a kid.” Well, I certainly feel 18…until I look in the mirror and see a dead Allman Brother.)

In that time, I’ve really enjoyed seeing—and, yeah, re-seeing—the horror classics. A little while back, I was asked by a reporter why I enjoy the classic horror flicks so much.

“I think my favorite thing about classic horror films is the imagination they inspire,” I told her. “The best of them deal with issues we grapple with today. For example: does science go too far? Or: how can I save myself from this stalker? Or even: how can I free myself from this cursed situation I didn’t ask for and don’t want? When you couple these themes with stylized set design, makeup effects, direction, and clever dialogue delivered with flair, magic happens.” (For the entire article, click here.)

Many of the makers of the classic horror flicks really had fun making those films. Check out what Erle C. Kenton—director of ISLAND OF LOST SOULS and THE GHOST OF FRANKENSTEIN, among others—had to say on the subject.

“They give us a chance to let our imagination run wild,” he told columnist Erskine Johnson. “The art department can go to town on creepy sets. Prop men have fun with cob webs. The cameraman has fun with trick lighting and shadows. The director has fun. We have more fun making a horror picture than a comedy.”

Part of the fun for me is researching the actors, directors, producers, screenwriters, et al., who made the flicks we Monster Kids love…in spite of—or, maybe, sometimes because of—their flaws.

And once in a while, my research turns up some really cool trivia that maybe you’ve forgotten you knew…or maybe never did.

Things that make you scratch your head and go, “What!?”

Or things that make you smile and go, “Wow!”

I hope I have a few of those for you in this column.

We’ll go in no particular order. I’ll just throw random information against our figurative fourth cyber-wall and see what sticks. If you laugh, frown, or learn something new, then it’ll be worth it.

Ready? Let’s start with the multi-talented George Waggner.

[Above: George Waggner, actor, screenwriter, director, and producer most famous for THE WOLF MAN (1941). But did you know that he was also a talented songwriter?]

You probably know that Waggner directed and produced THE WOLF MAN (1941). And that he wrote and directed MAN MADE MONSTER, which put Lon Chaney, Jr. on the horror map.

You may have known that Waggner wrote songs—more than one hundred of them, in fact. His “Sweet Someone” (1927), co-written with Baron Keyes, became something of a standard, and was recorded over the years by Billy Vaughn, Vic Damone, Tennessee Ernie Ford, and Don Ho.

But what I’ve just learned is that Waggner dreamed up the story for—and was the screenwriter on—a Monogram comedy called GIRL O’ MY DREAMS (1934).

He and composer Edward Ward wrote three songs for the picture: “Lucky Star,” “Joe Senior,” and “Thou Art My Baby.”

And belting out “Thou Art My Baby” in GIRL O’ MY DREAMS—with a broad, impressive baritone and an equally broad grin—is none other than Creighton Chaney.

[Above: Creighton Chaney (far right) sings “Thou Art My Baby”—a song by George Waggner and Edward Ward in GIRL O’ MY DREAMS (1934). Waggner also conceived the story and wrote the screenplay for the film.]

That’s right—Lon Jr.

And he sounds good! He obviously took after his mother, singer Cleva Creighton. (You can check out the performance on YouTube here, at least as of this writing.)

Oh, and Lon Jr. wrote songs as well. [1]

And Edward Ward, Waggner’s co-writer? He’s responsible for no less than SEVEN Oscar nominations, including Best Music, Scoring of a Musical Picture for PHANTOM OF THE OPERA (1943). [2]

Now, who directed that one again?

[Above: Composer Edward Ward with actress Susanna Foster. A frequent songwriting collaborator of Waggner’s, Ward was nominated for an Oscar seven times.]

Here’s another cool story. It’s about Boris Karloff, who—if we’re doing that Kevin Bacon six-degrees-of separation thing (if that still is a thing)—George Waggner directed in THE CLIMAX (1944)…which also features a score by Ward.

But I digress.

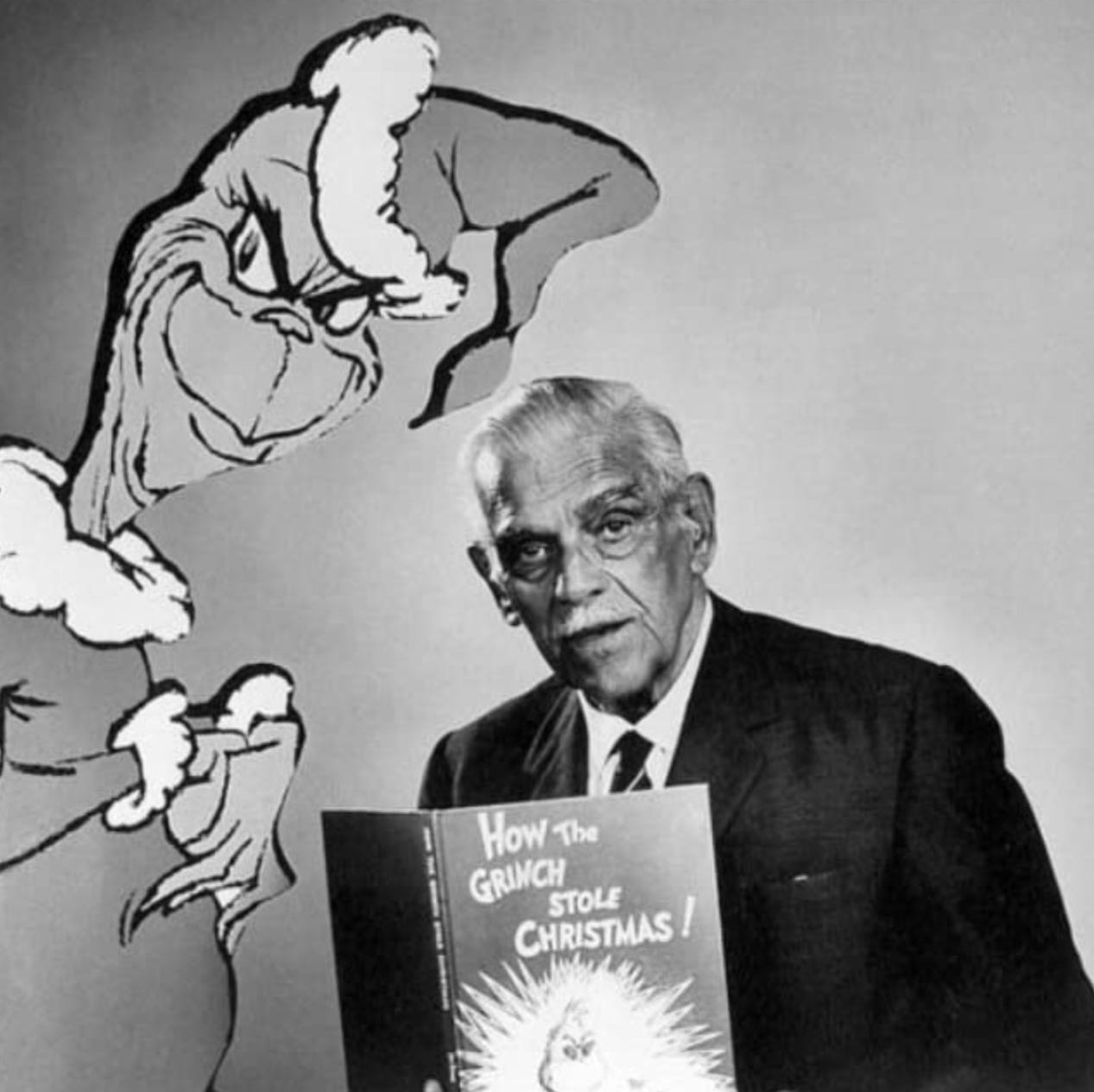

Let’s flash forward to 1966. Karloff provides the voice of the narrator and the titular character in the Chuck Jones-produced holiday cartoon HOW THE GRINCH STOLE CHRISTMAS, based upon the Dr. Suess book of the same name (click here to learn more about the creation of the show).

In spite of some mixed reviews, the special is a hit…such a hit, that Leo the Lion Records releases a children’s LP version of the soundtrack.

Which is a hit as well, and—of course—prominently features Karloff.

[Above: Boris Karloff and his animated counterpart in the TV Special HOW THE GRINCH STOLE CHRISTMAS (1966). An LP version of the show earned Karloff a Grammy.]

Early in 1967, Arthur Kennard—Karloff’s agent—gets a call from the Grammy Awards.

Karloff’s been nominated for a Grammy, he’s told, for Best Children’s Album. And he’s probably going to win it. Will he fly out to Hollywood for the ceremony?

Kennard isn’t sure. The soon-to-be 80-year-old Karloff is back in Britain, relaxing at his Sheffield Terrace home in London with his sixth wife, the former Evelyn “Evie” Hope Helmore, 63. A trip to Hollywood right now probably isn’t in the cards.

But Kennard knows Karloff likes to stay busy, so he decides to call and ask.

“Boris,” he says when he gets his client on the long-distance line, “I don’t have anything other than an awards ceremony for you to come to.”

“And what is that?” Karloff inquires.

“It’s the Grammy Awards.”

There’s a long pause. Karloff is, of course, familiar with the Oscars. And he’s been nominated for a Tony for best actor as Pierre Cauchon, the judge in the trial of Joan of Arc in THE LARK. [3] In addition, he’s been granted a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1960.

But this?

“A Granny?” he finally spits out.

“No, Boris,” Kennard responds. “Grammy—Grammy Awards.”

Karloff turns to Evie.

“It’s Arthur,” he’s likely to have said, “and he’s talking about something to do with grannies…?”

“What?” is Evie’s probable response. “Let me talk to him…”

“Hi, it’s Evie,” she says when she gets on the line. “I don’t understand at all.”

“It’s like an Oscar,” Kennard tries, “only it’s in the music business.”

This obviously doesn’t get through.

“Arthur wants you to come to some…Granny function,” Kennard hears her explain.

Boris isn’t interested. There’s no way he’s flying all the way out to L.A. for some “prize.”

Thursday, February 29, 1968. A Leap Year. The 10th Annual Grammy Awards ceremony is held, hosted by actor-comedian-radio personality Stan Freberg.

Of course, Karloff wins. Kennard accepts on his behalf.

“Keep it on your desk,” Karloff instructs Kennard when he hears.

Sometime thereafter, the Karloffs are back in L.A. of their own volition. Kennard picks them up at LAX and takes them to his office on Sunset Boulevard. Upon arrival, Kennard motions toward his desk.

“[T]here’s the Grammy,” he says.

Sure enough, the little statue that looks like a gramophone is right there in plain sight.

“Oh, a Granny,” Karloff jokes, obviously unimpressed. “It looks like a doorstop.”

Evie and Kennard’s secretary laugh out loud.

“It’s a marvelous prize,” Karloff cracks. “It looks like a doorstop.”

With that, he steps forward, snatches up the Grammy, opens Kennard’s office door…

…and keeps it propped open with his “prize.”

“It stayed there for a long time,” Kennard will relate in later years. [4]

[Above: Boris Karloff’s Grammy Award, accepted on his behalf by Arthur Kennard, Karloff’s agent. Karloff later used it to prop open Kennard’s office door.]

Speaking of prizes…

The Antoinette Perry Award for Excellence in Broadway Theatre—more popularly known as the Tony Awards—aren’t awarded until 1947.

Had they existed beforehand, Lionel Atwill would have undoubtedly been awarded at least one.

That’s right…the actor who graced the screen with marvelously wicked performances in such classics as MYSTERY OF THE WAX MUSEUM (1933), MURDERS IN THE ZOO (1933), THE HOUND OF THE BASKERVILLES (1939), SON OF FRANKENSTEIN (1939), and MAN MADE MONSTER (1941) was for years the toast of Broadway.

So much so, that THE WASHINGTON HERALD trumpets on June 16, 1918: “Lionel Atwill…has probably achieved a larger measure of success during the past season in New York than any other actor in the public eye today.”

Atwill reaches his pinnacle on Wednesday, December 23, 1920, when he stars with second-wife Elsie Mackay in DEBURAU.

His understudy is Frederic March.

Written by Sacha Guitry, Atwill stars as Deburau, a once-famous mime whose life is shattered when he discovers that the love-of-his-life Marie (Mackay) is actually a prostitute. His later attempts to become successful again on stage are rebuffed by cruel crowds. But he trains his son Charles in his art, and achieves a triumph of sorts when Charles becomes “a new and greater Deburau.”

“[I]t may well represent the greatest triumph of his entire career—on both stage and screen,” Neil Pettigrew, Atwill’s biographer, writes. “The play also deserves highlighting because it is almost completely forgotten today, yet in the 1920s it was a sensation. Atwill was acclaimed by the critics as one of the greatest stage actors of all time.”

What might have been had the Tony existed…

[Above: Lionel Atwill in DEBURAU (1920) on Broadway. Neil Pettigrew, Atwill’s biographer, considers the play to be Atwill’s greatest achievement.]

From there, with his wife often performing beside him, Atwill owned the boards in THE GRAND DUKE (1921). THE COMEDIAN (1922). THE OUTSIDER (1923). CAESAR AND CLEOPATRA (1924). Everything in life is going gangbusters.

It’s during the development of a play called DEEP IN THE WOODS in 1925 that troubles occur.

Elsie doesn’t come home one night after rehearsal. Atwill suspects that she’s having an affair with fellow DEEP IN THE WOODS actor Max Montesole. After all, she’d had an affair with Atwill himself when they’d first met, breaking up Lionel’s first marriage. So, he knows she’s not above such things…and neither is he.

Atwill’s friend, 32-year-old actor Claude Beerbohm, happens to be present that evening. He watches as a distraught Lionel nervously traverses the Long Island premises, retrieving two pistols.

I ought to shoot him, a furious Atwill spits out. I ought to throttle him!

But then—as the consequences obviously occur to him—Atwill begins to calm down.

He decides to hire two detectives. Together with his attorney, the detectives, and his chauffeur, Atwill pays a surprise visit to Elsie and Max at the Atwill’s Manhattan digs.

What he finds floors him.

Packing cases fill the room. Elsie and Max are obviously planning a secret midnight run. Then, a member of the staff swears that Elsie has been staying in the place as Mrs. Montesole.

It’s obvious that she’s been unfaithful. The marriage ends. DEEP IN THE WOODS never opens.

Years later, Atwill—while making MURDERS IN THE ZOO—takes a liking to a 15-foot-long python. He decides to take the critter home.

Oh, and the name of Atwill’s new, snaky companion? Elsie, of course. [5]

[Above: Atwill as villain Eric Gorman is dispatched by a python in MURDERS IN THE ZOO (1933). Atwill took a liking to the snake and brought it home…much to the consternation of his third wife, Louise.]

Here’s a funny one about Bela Lugosi, courtesy of the book NO TRAVELER RETURNS by Gary D. Rhodes and Bill Kaffenberger…which is highly recommended to anyone who’d like to learn more about Bela’s experiences in the theater in the mid-1940s.

This one takes place in July, 1948. ABBOTT AND COSTELLO MEET FRANKENSTEIN, which Bela had shot between February and March, is out nearly a month and is a sizable hit.

But none of that money is trickling down to Bela. He’s been paid his $8000 for the film—worth about $93,000 today—and that’s all Universal-International is obligated to do.

As it turns out, the film will be Bela’s last for a major studio.

But he doesn’t know this as he prepares to open yet another stage version of DRACULA, this time in Denver Colorado for the Artists Repertory Theatre.

The play will run here from July 8 to July 13. Bela’s longtime friend, actor Dan Durston, is also featured in the production. [6]

“I’m going to take all of you out to dinner,” Bela announces one night. “There is a wonderful Hungarian restaurant here.”

This raises Durston’s eyebrows a little.

Sure, Bela loves a good time with close friends, fine food, drinks, and cigars.

But Durston also knows that Bela is bad with money…and is often in danger of going broke.

So taking six people out to dinner at a fine restaurant is probably something Bela should not—or maybe could not?—do.

[Above: One of the great joys in Bela Lugosi’s life is to go out to dinner with friends. He’s pictured here—with Mickey Mouse!—in an unknown restaurant in 1933.]

But this doesn’t stop Lugosi. He enters the restaurant like royalty. The owner rushes over and embraces him. The musicians break out in what Durston describes as “a Hungarian rhapsody.”

“[Y]ou’d have thought he was President of the United States,” Durston marvels.

“Order whatever you want,” Bela announces when everyone gets seated.

What did they eat? Goulash? Stuffed peppers? Schnitzel? Cholent? The exact nature of the feast has been lost to history, but we can be certain that the dishes piled up a-plenty and that the alcohol generously flowed. Bela would insist on no less.

Throughout the banquet, the owner—obviously a bit star-struck and over-the-moon happy that Bela is here—keeps coming over and breaking into the conversation. Durston knows that, in general, Bela is very happy to converse with fans. However, Durston finds these constant interruptions to be a bit annoying.

Is Bela getting aggravated too?

If he is, he certainly isn’t showing it—Durston actually admires how graciously Bela is handling the situation.

Then, the after-dinner drinks—including Napoleon brandy—arrive.

“Bela really can’t afford this,” Durston finds himself thinking yet again.

Meanwhile, the owner—like clockwork—returns to the party.

“Is everything okay?” he wants to know.

It’s at this point that Bela dramatically rises from his chair and embraces the owner warmly.

“How wonderful of you to compliment this meal,” he intones in his one-of-a-kind voice….loudly, so everyone in the restaurant can hear. “I shall never forget it! I shall speak about your restaurant everywhere I go!”

The owner stands in stunned silence. He’s just been thanked in public by Bela Lugosi for providing a free meal. What choice does he have now but to comply?

“And so we walked out without paying a dime,” Durston will tell Gary Rhodes with a laugh in 1996, “all six of us.”

Later, Lugosi explains to Durston exactly how his stunt will actually benefit the restaurant owner.

“He got his money’s worth,” Bela notes, no doubt with a twinkle in his eye. “All of his regular customers got to see a famous actor. And he’ll have stories to repeat year after year.”

From where I sit, I’m guessing this wasn’t the first time Bela Lugosi had ever pulled a trick like this. Nor was it likely to be the last…

This next bit of trivia is tenuously tied to Bela…and to Lionel Atwill as well.

Let’s flash back to October 20, 1942, Bela’s 60th birthday.

It’s also the day Universal releases NIGHT MONSTER, the last time Bela is top-billed in a picture for a major studio.

[Above: Bela Lugosi—far left—in NIGHT MONSTER (1942). This is the last time Bela will be top-billed in a film for a major studio.]

Directed by Ford Beebe, NIGHT MONSTER is—as several film critics have pointed out—basically a rehash of DOCTOR X. (Atwill even plays a doctor in it.) A series of grisly murders are happening in a swamp surrounding the estate of one Kurt Ingston (played by Ralph Morgan). An investigation results, and after a few supporting characters are mysteriously killed, the unlikely culprit is captured and neutralized.

For those who have yet to see the film, I’ll say no more here…except that The Wolf Man’s feet make a cameo appearance during the climactic scenes.

That’s right, The Wolf Man’s feet…without Lon Chaney, Jr. in them.

As it turns out, those feet—featured so prominently in THE WOLF MAN (1941) when Larry Talbot walks his thorny way—were actually a pair of boots [7]. And in a time before we Monster Kids were able to stop and study every frame of our favorite films, it would be a no-brainer for somebody on the production to say, “Oh, you need to show some monster feet? Well, we’ve got The Wolf Man’s in storage over in the prop department. That’ll save you a few bucks making new ones.”

As for top-billed Bela? He serves as a red herring.

[Above: The Wolf Man’s feet—without Lon Chaney, Jr. in them—make a cameo appearance in the climactic scene of NIGHT MONSTER (1942).]

Okay, here’s our last bit of trivia for now. Again, we can we can tenuously tie it to Bela Lugosi, since it involves ABBOTT AND COSTELLO MEET FRANKENSTEIN (1948).

But it’s not really about Bela this time, either.

As every Monster Kid knows, the Frankenstein Monster throws Dr. Sandra Mornay—Dracula’s evil scientist sidekick in the film—through a huge plate glass laboratory window during the climactic scenes.

And, as most Monster Kids know, Glenn Strange—playing the Monster—badly injured his foot on the first try. Strange’s friend Lon Chaney, Jr. stepped up the next day, donning the Monster’s makeup and costume and throwing Mornay through the breakaway glass himself.

But who, exactly, did Chaney chuck?

Most Monster Kids are aware that Lenore Aubert plays Sandra in the film. But Ms. Aubert is not hanging on the wire rigging for the stunt with Chaney. [8]

Rather, it’s stunt performer and sometime actress Helen Thurston.

[Above: Stunt performer Helen Thurston carries 200-pound comic Lou Costello on her back behind the scenes of RIDE ‘EM COWBOY (1942). Thurston firmly believed that anything a male stunt man could do, a stunt woman could replicate.]

Born in Oregon, Thurston is soon to turn 39. And she’s certainly packed a lot into those years.

She starts out as an acrobat. Her training program is epic. The daily three-hour routine includes golf, tennis, riding a unicycle, cracking a sizable whip, and throwing knives.

“I think that sometimes I leave the neighbors a trifle aghast,” she’ll relate later to writer Ronald Hayes.

Aghast neighbors or no, her dedication to physical fitness pays off. The blonde-haired, blue-eyed Thurston carries 122 muscular pounds on her five-six frame.

A phone call from RKO in 1937 changes the then 29-year-old Helen’s life. Someone at the studio has mixed her up with a stunt performer. When Helen arrives, she assesses the situation and agrees to the job.

Her first assignment is to double Katherine Hepburn in BRINGING UP BABY (1938). Her first stunt is a daring tumble down a flight of stairs.

She’s hooked.

“That started me off on a career I thoroughly enjoy,” she’ll remark.

She grabs a trampoline and sets it up outside her house to practice falls…something else, perhaps, for the neighbors to be aghast over.

She also notices something at the studios that she doesn’t like: male stunt performers are often dolled up in dresses and wigs to perform gags for featured actresses.

As her credits rack up—DESTRY RIDES AGAIN (1939), JUNGLE GIRL (1941), RIDE ‘EM COWBOY (1942) with Abbott and Costello—so does her determination to change this practice.

“There’s no stunt that a man can do that a woman can’t duplicate,” she’ll say with fire. “Believe me, I know. I’ve done them all.”

So, in addition to exercising, Helen eats like a maniac to build even more muscle.

“I am a very heavy eater,” she’ll note, “a meat, potatoes, and gravy girl, so to speak. I have to eat lots of meat to keep up my strength.”

Along the way, she marries former vaudevillian and fellow stunt performer Charles J. “James” Fawcett. Fawcett hails from San Francisco and has come to Hollywood for work in movies. Together, Helen and James have a son, also named James. They settle in at 2435 North Beachwood Drive in Hollywood.

Meanwhile, Helen crashes cars into telephone poles.

Jumps off cliffs.

Falls out of windows.

Gets knocked around by explosions.

And she hangs a sign on her wall: “You’re only as good as your last stunt.”

“I try to make every one letter perfect,” she vows

Sadly, tragedy strikes on Tuesday, June 9, 1942.

James Fawcett has finished work for the day on Republic’s chapter serial KING OF THE MOUNTIES and is heading home. He’s speeding west on Ventura Boulevard on his motorcycle when he attempts to pass a car driven by one Ralph Harolde, 38. [9]

Things go seriously wrong when Harolde turns into his driveway at 17211 on Ventura. Fawcett crashes his bike into the side of Harolde’s car. The impact sends Fawcett flying through the air. He then slams onto the pavement.

Hard.

He’s raced as quickly as possible to Van Nuys Receiving Hospital, then moved to Wilshire Hospital.

He’s suffered a skull fracture, a busted jaw, numerous other broken bones, various dislocations, and serious cuts.

Reporting on the incident, the SAN FERNANDO VALLEY TIMES somewhat cruelly adds, “he may not be around for a long, long time.”

Sadly, the paper is correct. Fawcett soon dies at Wilshire—aged only 35—leaving Helen, young James, and his mother Helen Howatt behind. He’s buried at Forest Lawn after a service at the Wee Kirk o’ the Heather.

True to her character, Helen Thurston soldiers on. Though she pretty much takes 1943 off from films—appearing only in a small part as a carhop in PILOT #5—she’s back full-time doing stunts by 1944 in movies such as SAN FERNANDO VALLEY (1944), THE STRANGE LOVE OF MARTHA IVERS (1946), and DAUGHTER OF DON Q (1946).

By 1948, writer Ronald Hayes is comfortable claiming in print that Helen’s “feats have become legendary in Hollywood,” and that she’s “filmland’s most celebrated stunt girl.”

So, when the makers of ABBOTT AND COSTELLO MEET FRANKENSTEIN need her to get tossed out of a huge window by the Frankenstein Monster, it’s no sweat for Thurston.

And she’ll be paid $55.00…worth a little more than $680.00 at this writing.

Tuesday, March 16, 1948. Lon Chaney, Jr. is suited up as the Frankenstein Monster. Helen Thurston is doubling Lenore Aubert. It helps that she’s wrapped in surgical garb, complete with cap and facemask.

Director Charles Barton yells, “Action!”

Chaney—with the help of the wire rigging, and the fact that Helen’s stiff right arm on his left shoulder strategically braces her—hoists Thurston over his head and flings her through the prop laboratory window.

The take is a good one—and is still very effective when seen today—so everyone concerned is happy.

Everyone, that is, except Thurston.

Because, during the course of the stunt, some shards of the breakaway glass—a concoction made up of sugar, corn syrup, and water—get caught in her eyes.

She has to be rushed to the hospital.

Universal-International—perhaps attempting to ward off a lawsuit?—ups her pay to $300…worth a bit more than $3700.00 at this writing.

[Above: Lon Chaney, Jr.—doubling Glenn Strange—throws Helen Thurston—doubling Lenore Aubert—through a laboratory window in ABBOTT AND COSTELLO MEET FRANKENSTEIN (1948).]

If the studio execs are worried that Helen Thurston is coming after them, they needn’t be. She recovers, and when she’s asked later in the year what her most serious injury has been, the ‘phony glass in the eyes’ incident isn’t even on her radar.

Rather, she cites two dislocated vertebrae.

Thurston continues to work steadily throughout the 1950s and 1960s. A PLACE IN THE SUN (1951). THE MAN WITH THE GOLDEN ARM (1955). IT’S A MAD MAD MAD MAD WORLD (1963). MARY POPPINS (1964).

Her last screen credit is HILLBILLYS IN A HAUNTED HOUSE (1967). She dies on April 23, 1979, in Costa Meza, California.

I wonder how many folks in her Costa Meza neighborhood knew that she’d once been flung out a window by the most famous monster in films?

Did you know? Rondo-Award winning filmmaker Thomas Hamilton is in the process of making THE CHANEYS: HOLLYWOOD’S HORROR DYNASTY, which is inspired by my book, CHANEY’S BABY. (I’m also a producer on the film.) If you’d like to support the project, click here and see what’s going on. Thanks!

NOTES

[1] See Beck, p. 228.

[2] Ward’s other nominations include Best Original Song (“Always and Always”) MANNEQUIN (1937); Best Music, Musical, ALL-AMERICAN CO-ED (1941); Best Music, Drama, TANKS A MILLION (1941); Best Music, Drama, CHEERS FOR MISS BISHOP (1941); Best Music, Musical, FLYING WITH THE MUSIC (1942); and Best Original Song (“Pennies for Peppino”), FLYING WITH THE MUSIC (1942).

[3] He loses to Paul Muni as Henry Drummond in INHERIT THE WIND.

[4] Account drawn from Nollen, pp. 243-244.

[5] Anger, p. 94. Of course, Anger’s credibility has been attacked over the years, so readers are free to draw their own conclusions. What is true is that the snake kills Eric Gorman—Atwill’s character—in the film. Interestingly, Atwill’s affection for the creature is supposedly the first crack in his marriage to Louise Cromwell Brooks MacArthur, Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s ex-wife. As for Elsie and Max? They get married in 1933. They are still together when Max dies in Australia in 1942, at the age of 54. Elsie marries James Stanley Smith in 1957. She dies in Hawthorn, Victoria, Australia in 1963 at the age of 69.

[6] Durston tells Rhodes in 1996 that he’s known Lugosi since he was a kid, and that his father had known Lugosi back in Europe.

[7] Probably fashioned by Ellis Burman, the special effects technician, who—according to makeup artist Rick Baker—was responsible for whipping up the studio’s rubber props (which included the wolf’s head on Larry Talbot’s cane). Pierce would have taken over from there, fashioning the claws and attaching the yak hair.

[8] Aubert may have been in the rig the first time, when Strange hurt himself; imdb.com makes this claim, and Greg Mank supports it…at least in 1981 (see Mank, IT’S ALIVE, p. 161).

[9] Apparently not the actor by the same name, though coincidentally actor Harolde was involved in a fatal crash in 1937. Also, actor Harolde had just turned 43 when this crash occurred in 1942…though the papers could have gotten his age wrong.

SOURCES

Anger, Kenneth. HOLLYWOOD BABYLON II. New York: E.P. Dutton, Inc., 1984. Print.

Beck, Calvin Thomas. HEROES OF THE HORRORS. New York: Collier Books, 1975. Print.

“Charles J. Fawcett.” THE LOS ANGELES TIMES. June 11, 1942, p. 14. Print.

Fleck, Bill. CHANEY’S BABY. Wurtsboro, NY: Just Pay the Ransom Music, 2021. Print.

Hayes, Ronald. “Clever Stunt Girl.” THE OAKLAND POST ENQUIRER. October 21, 1948, p. 36. Print.

Johnson, Erskine. “Johnson in Hollywood: Into the ‘Mush.’” THE LONG BEACH SUN. May 13, 1944, p. 8. Print.

Mank, Gregory William. HOLLYWOOD’S MADDEST DOCTORS. Baltimore: Luminary Press, 1998. Print.

Mank, Gregory William. IT’S ALIVE! New York: A.S. Barnes & Company, Inc., 1981. Print.

“Movie Stunt Man Injured in Auto Smash.” SAN FERNANDO VALLEY TIMES. June 12, 1942, p. 35. Print.

Nollen, Scott Allen. BORIS KARLOFF: A GENTLEMAN’S LIFE. Baltimore: Marquee Press, Inc., 1999. Print.

Pettigrew, Neil. LIONEL ATWILL: THE EXQUISITE VILLAIN. Baltimore: Midnight Marquee Press, Inc., 2014. Print.

Rhodes, Gary D. and Bill Kaffenberger. NO TRAVELER RETURNS: THE LOST YEARS OF BELA LUGOSI. Albany, Georgia: BearManor Media, 2016. Ebook.

Note: The photos utilized herein are intended for educational purposes only. I do not own the copyrights.