CLASSIC HORROR BEHIND THE SCENES: Lon Jr. and ABBOTT AND COSTELLO MEET FRANKENSTEIN

A&C MEET FRANK is the gateway film for many Monster Kids. But one of the stars grew to hate it.

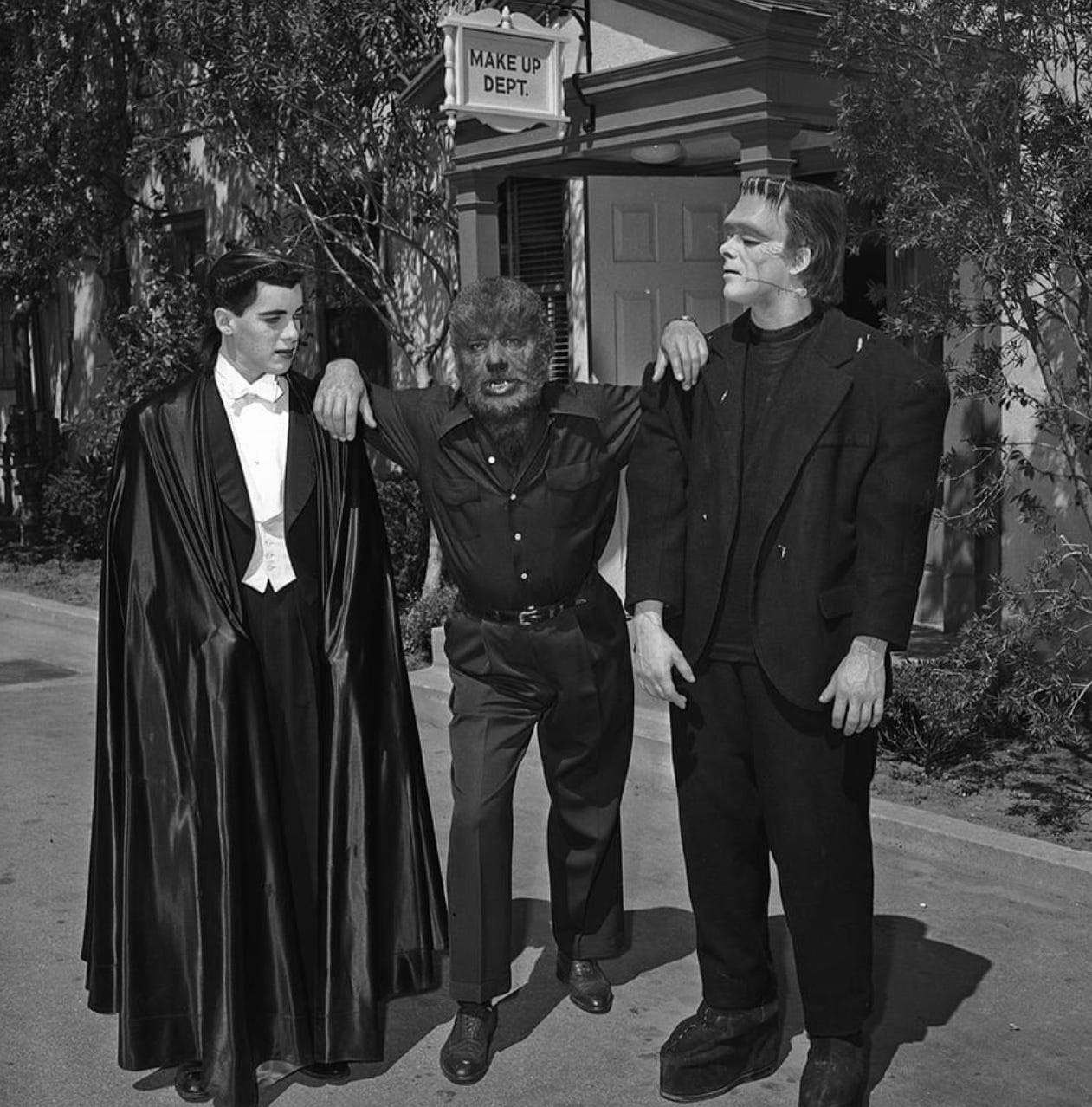

[Above: Ron Chaney, Lon Chaney, Jr., and Lon Ralph Chaney on the set of ABBOTT AND COSTELLO MEET FRANKENSTEIN. Chaney, Jr.’s sons were made up by makeup artist Jack Kevan upon visiting the set.]

By Bill Fleck, author of the Rondo-nominated book CHANEY’S BABY, available here.

Did you know? Two-time Rondo-Award winning filmmaker Thomas Hamilton is in the process of making VINCENT PRICE AND THE ART OF LIVING. If you’d like to support the project, click here and see what’s going on. Thanks!

Check out other articles on this Rondo-nominated blog by clicking here.

Much of this article is drawn from my book CHANEY’S BABY, with some updates.

February 5, 1948 is a wet Thursday morning in Los Angeles, but nobody’s complaining. Overnight, soaking rains have finally broken what The Los Angeles Times describes as “Southern California’s worst drouth in 70 years.”

Lon Chaney, Jr. has suffered a drought as well. From 1941 through 1945, he’d averaged six-to-seven screen appearances per year. But that’s when he was with Universal.

Since then, his proposed career as a comedian at Paramount hasn’t worked out. As a result, he’s subsequently appeared in only three films.

The fact that he’s recently been featured in a syndicated, comic-book style newspaper ad for Trim Hair Tonic—tied to his appearance in ALBUQUERQUE—is small comfort. [1]

Given the limited offers, it’s no surprise that he and WOLF MAN writer Curt Siodmak are forging a plan for their own production company—one that will focus on horror films.

“The Valleyite, who will also star in the pictures, hopes to develop several new monsters that will top even Frankenstein,” The Valley Times reports.

One potential character? The Lizard Man.

[Above: Chaney with Bob Hope in MY FAVORITE BRUNETTE (1947). After being released by Universal, Chaney planned to reinvent himself as a comic. The plan ultimately didn’t work out. Interestingly, Chaney preferred Hope’s style of comedy to that of Abbott and Costello.]

With production beginning on THE BRAIN OF FRANKENSTEIN, Chaney can’t help having mixed feelings. On the plus side, he’ll be playing Larry Talbot—billed this time as The Wolfman—again. And the $10,000 he’s getting—worth a bit less than $129,000 at this writing—is certainly better than he’ll pull down for stage plays like BORN YESTERDAY or OF MICE AND MEN revivals.

There’s also the fact that Jack Pierce—never a Chaney favorite—has been canned. Bud Westmore runs the makeup department now, and he’s cut Chaney’s time in the chair to only an hour by supervising the creation of foam rubber Wolfman appliances that his assistant Emile LaVigne will apply.

But there are downsides, too. Chaney is still angry at Universal for cutting him loose late in 1945. He can only take pleasure in the fact that new production chief William Goetz—Louis B. Mayer’s son-in-law—has nearly bankrupted Universal-International by insisting on making highbrow pictures.

At home, things are hectic as well. Chaney and his second wife Patsy, apparently unable to have children of their own, have been desperate to adopt. But those plans continually fall through.

Too, there are Lon’s teen sons with his first wife Dorothy Hinckley: Lon Ralph, 19, and Ronald Creighton, who’ll soon be 18. True, Chaney and Dorothy’s contentious divorce is nearly twelve years in the past. But since then, Dorothy has remarried twice—first to Edgar H. Mohan in October of 1940, and then to her current husband Loren G. Symons in October of 1945. Lon Ralph and Ron have taken up residence with their father and stepmother, perhaps as a result. No one in the famously private Chaney family has ever specifically said so, but events soon to unfold indicate that Lon and Patsy aren’t immune to the tensions that invariably emerge in blended families.

And then there’s Abbott and Costello.

Chaney knows the boys. He’d done a supporting role in HERE COME THE CO-EDS with them back in 1945, and he’d enjoyed the experience. But he’s not a fan of slapstick in general, preferring Bob Hope’s comic stylings. So even though the script as written treats his character straight, he’s not sure how The Wolfman will fare going up against Costello’s penchant for outrageous improvisation.

“We monsters should get together and form a union,” he’d said back in 1944. “The public comes to see us in a fantastic ghost, or mummy, or zombie, or Frankenstein, or Wolf Man picture, and we expect the audience to take us seriously. Thus far, they have. But now what can we expect when we let ourselves be cast in roles where the horror pictures are spoofed?”

He’s not the only one who’s wary.

Goetz, for example, absolutely hates Abbott and Costello. And some of his animosity toward them is well deserved.

[Above: Chaney and Lou Costello share a laugh on the set. Chaney liked Costello, but didn’t like how The Wolfman was treated like a clown in the film…due in many ways to Costello’s penchant for ad-lib.]

Bud Abbott and Lou Costello have been a team since 1936. Massive success on stage and in radio results in a movie contract with Universal. Their first starring film, BUCK PRIVATES, is made for $180,000 in 1941—the exact same cost as THE WOLF MAN.

Studio suits were beside themselves with joy when THE WOLF MAN made its first million.

BUCK PRIVATES rakes in $10 million.

Perplexed but giddy, Universal squeezes as many movies out of the team as it can. By the time they start THE BRAIN OF FRANKENSTEIN, they’ve got 21 features behind them.

Only Costello’s 1943 battle with rheumatic heart fever—and the accidental drowning of his infant son, Butch, in November of that year—puts the brakes on their whirlwind schedule.

“It’s slow in Hollywood,” goes the joke. “Abbott and Costello haven’t made a picture all day!”

By 1948, however, the team isn’t the cash machine it once was.

Plus, there are the boys themselves. Universal executives view them as a big-time pain in the ass.

William “Bud” Abbott, 52, comes from a long line of theatrical folks. Offscreen, he’s a quiet man but a sharp dresser. He smokes his cigarettes out of a holder. He gambles habitually and loses stacks of cash. He can’t remember anybody’s name, so he calls everybody “Neighbor.”

He also lives in deathly fear of his epilepsy.

His fits are terrible when they hit. He starts drinking by late afternoon to help him cope. This ensures that he’s done working when the evening comes.

“Nothing’s funny after five o’clock,” is his mantra.

Costello, born Louis Francis Cristillo, will turn 42 on March 6. Offscreen, he’s a five-foot-four, 200-pound, cigar-chomping ball of fire. While he’s basically a kind and generous guy, his temper tantrums are legendary. The death of his son has made them even worse.

Like Abbott, Costello is native of New Jersey. Also like Abbott, Costello is a habitual gambler. Unlike Abbott, Costello is a poor loser. In spite of the fact that the team makes more than $100 grand per film—and Costello gets sixty percent of it [2]—Lou is constantly broke and hungry for money.

Add the fact that Abbott and Costello’s film sets are like a zoo. When they aren’t fighting with each other, they’re wreaking havoc on their co-stars, Evelyn Ankers among them. While shooting HOLD THAT GHOST (1941), they decree that Ankers is “stuffy”—and gift her with a suitcase filled with Kotex.

“I was always glad to find a wall to stand against, or a chair to sit in between takes,” she’ll recall years later.

THE BRAIN OF FRANKENSTEIN is developed by producer Robert Arthur. The 38-year-old former screenwriter has already worked with the comedy team on BUCK PRIVATES COME HOME (1947) and THE WISTFUL WIDOW OF WAGON GAP (1947). He’s witnessed the wars between Abbott, Costello, and Goetz. The current skirmish involves bigger budgets for their films. There’s no way in Hell that Goetz and his associate Leo Spitz are going to approve. When Costello demands that he and Abbott be paid $25,000 more per film, Goetz suspends them.

[Above: Universal-International studio chief William Goetz with actress Joan Fontaine in 1947. In spite of Abbott and Costello’s obvious box office success, Goetz hated the duo and had little faith in THE BRAIN OF FRANKENSTEIN project.]

Meanwhile, the budget for their new project is locked at $750,000.

But what, exactly, will that new project be?

While chatting with a couple of writers, Arthur has a brainwave: what about pairing up Abbott and Costello with the Frankenstein Monster?

“That’s the greatest idea for a comedy that ever was!” says screenwriter Robert Lees.

Arthur, Lees, and Frederic Rinaldo eventually develop the hook: The Monster is getting too smart. A mad scientist decides he needs to dumb the creature down. Costello’s screen persona—that of a naïve child-man—makes his brain the perfect solution!

What about Dracula? adds one of the writers, probably remembering monster rallies like HOUSE OF DRACULA. What if he had possession of The Monster?

“And why not have The Wolfman to warn the boys?” suggests another.

They decide to toss in The Mummy, The Son of Dracula, and The Invisible Man as well.

The plan is set. Screenwriter Oscar Brodney (MEXICAN HAYRIDE, HARVEY) does up a draft, followed by Bertram Millhauser (SHERLOCK HOLMES FACES DEATH). Finally, Lees and Rinaldo, who have been writing Abbott and Costello pictures off and on since HOLD THAT GHOST, team up. They pass their draft on to John Grant, A&C’s longtime joke-meister. [3]

Meanwhile, Arthur assembles the cast. He gets Chaney as The Wolfman. He secures Glenn Strange once again for The Monster. And he brings Bela Lugosi back to Universal for the first time since FRANKENSTEIN MEETS THE WOLF MAN as Dracula.

Rounding out the cast are Lenore Aubert, 34, and CAT PEOPLE’S Jane Randolph, 33, both of whom are playing women who fake romantic interest in Costello’s character to achieve their (opposite) ends.

But problems occur almost immediately.

To begin with, Goetz doesn’t want to read the finished script.

“I don’t think those guys are funny,” he tells Arthur. “If I read the script, I might not think that it was funny, and anything I say might harm your picture. Good luck and God bless you.”

Costello, on the other hand, does read the script.

He hates it.

“You don’t think I’ll do that crap, do you?” he explodes. “My five-year old daughter can write something better than that!”

Arthur is taken aback. First of all, he’s never known Costello to have ever read a script before. Secondly, he’s sure he has a hit on his hands…if he can get the comic to play in it.

“You do the picture,” Arthur responds, “and I’ll pay you fifty thousand dollars cash for your share of the profits.”

“Fifty G’s right now?”

“Right now.”

Costello is on board…temporarily.

Saturday, February 14, 1948. Bela Lugosi, 65, is on set at Universal-International as Dracula.

Lugosi’s hair is darkened, his lips are painted, and his face is caked with powder. He’s just postponed a London stage revival of DRACULA to be here because the $8000 he’ll be paid by the studio is much better money (it’s the equivalent of $103,000 at this writing). And he desperately needs money. To that end, he’s hoping to convince the producers to make at least two more Dracula films.

“There is enough material in the original novel for half a dozen pictures,” he asserts.

“He was quite a gentleman,” co-star Jane Randolph will say. “He really liked doing Dracula. He did not hint that he felt trapped by the character. He seemed proud of it.”

He’s about to deliver one of his greatest performances. But subsequent Lugosi/Dracula films will never materialize.

[Above: Bela George Lugosi with Chaney on the set. Bela’s father arguably stole the film as Dracula.]

Directing the picture is Charles T. Barton. The five-foot-two, 45-year-old Sacramento native is working on his fifth Abbott and Costello production. His main appeal for Universal-International is that he gets along with Costello.

“A lot of people showed fear, and that’s what he loved, so he’d walk all over them,” Barton will tell Greg Mank about Costello years later. “But for some reason, with me—and I don’t know why in the hell it was—we got along even better than brothers.”

Barton is no stranger to Chaney, either. He had directed Chaney in Rose Bowl back in 1936. Conceding that Chaney was “a Frankenstein when he was on the bottle,” he’ll describe the actor’s behavior on THE BRAIN OF FRANKENSTEIN in this manner:

“Lon junior was as gentle as a little lamb—now I’m talking about with me. He was so kind—he’d do anything. He was really cooperative. Of course, he had that drinking problem…oh God, awful. By late afternoon, he didn’t know where he was. He had the problem all through his life, even when he was very young. I don’t know why. I guess he knew.”

This being an Abbott and Costello set, things are typically chaotic.

There’s Abbott and Costello’s paid jester Bobby Barber, bringing in pies to throw and getting eggs cracked on his bald head. The diminutive, shifty-eyed actor even scores a bit part in the film as a waiter.

Then, there’s Costello’s refusal to learn his lines from a script he still dislikes.

“He just wanted to stand up and do routines,” Barton explains.

Several bits of business from Grant ameliorate Costello’s concerns a little, though Lees and Rinaldo feel such things don’t belong in the script.

“Grant was a problem for us,” Lees will remember in 2008. “After we’d work very hard to get a story together, Grant would come in with something and they’d put it in just because it was from Grant.”

These fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants antics don’t sit well with Lugosi. Initially amused, Lugosi’s tolerance erodes as takes are blown and time is wasted.

“There were times when I thought Bela was going to have a stroke on the set,” Barton remembers. “You have to understand that working with two zanies like Abbott and Costello was not the normal Hollywood set. They never went by the script.”

Lugosi handles the situation by glaring at the offenders in his inimitable way.

“We should not be playing while we are working,” he’ll intone more than once.

Not that it does any good.

Abbott—who generally takes his cues from Costello—isn’t in a good mood, either. Arriving on the set from vacation with three broken ribs—he’s been tossed by a horse in Phoenix—Bud’s more than happy to participate in card games that eat up two or three production days.

“Be there in a minute, Neighbor,” he’ll respond when called to work, though he has absolutely no intention of following through.

Lou is typically less polite: “Get lost.”

There are moments of levity. Strange can’t help but laugh while shooting scenes with Costello, encouraging more ad-libs from the already off-script comic. And one fine day, the exotic Aubert puts Strange—in full makeup—on a leash for a walk outside, accompanied by Abbott, Costello, and Chaney…also in full makeup, much to the shock and delight of tourists.

“It was fun,” Randolph remembers. “Abbott and Costello were very funny every day, and they were always nice to me…A lot of the crew worked with them before, so they were used to them.”

But more typical are the times when the comics go home for the night…and don’t return until what feels like days later. As a result, the film will take a week longer than scheduled, costing $33,000 more.

“All three of the ‘monsters’ were the nicest,” Barton will say. “The real monsters were Abbott and Costello!”

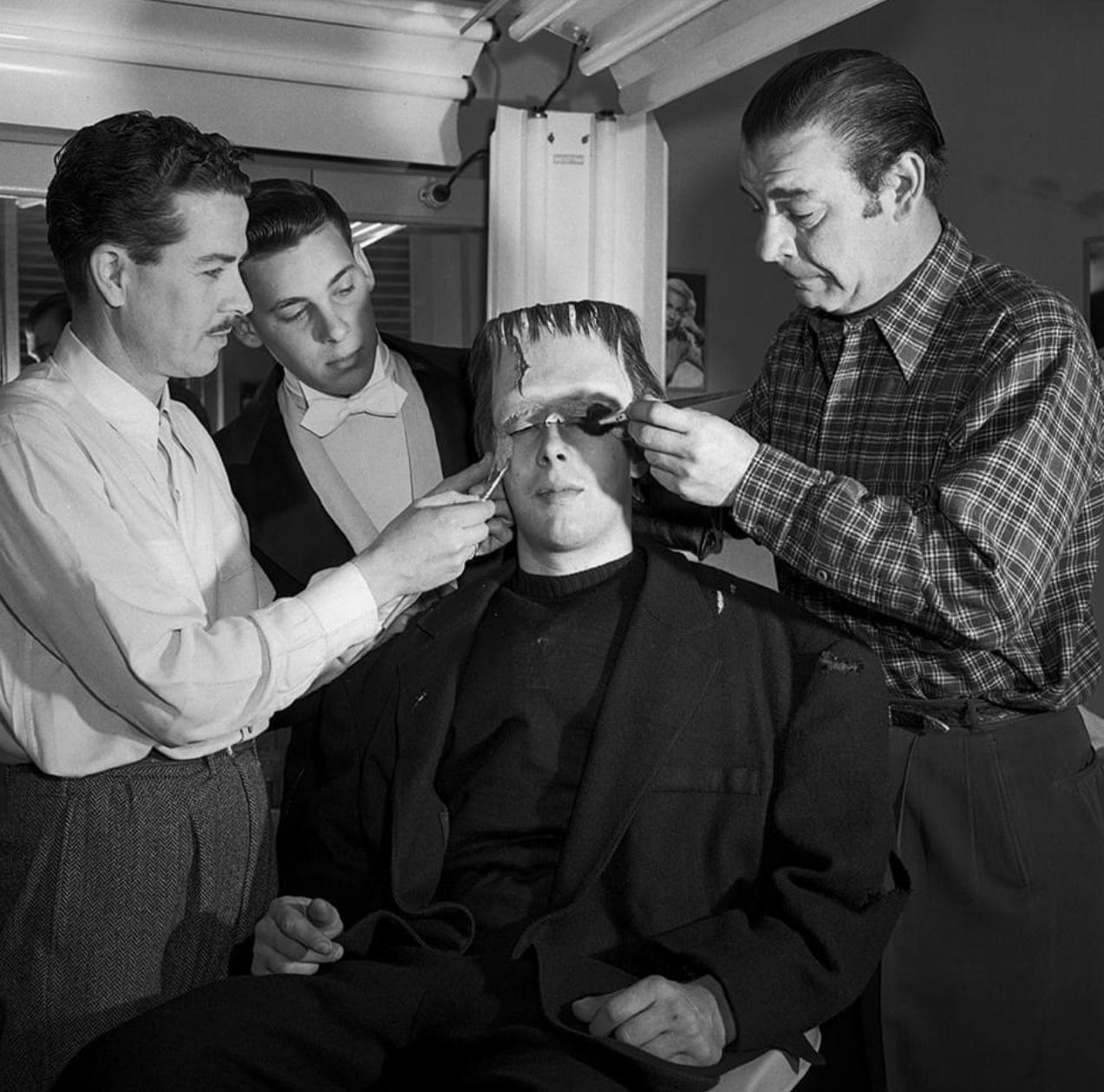

For his part, Chaney is mostly enjoying the shoot. Bud Abbott’s niece Betty remembers him lurking in his dressing room, hoping to pounce on some unsuspecting victim in the same way he tormented Evelyn Ankers. He also takes photos with Lugosi’s son, Bela George. And then, there’s the day Chaney brings Lon and Ron to work with him…only to pop them into the makeup chair, helping Westmore’s assistant Jack Kevan turn Ron into Dracula and Lon into Frankenstein’s monster.

[Above: Chaney helps Jack Kevan apply the Frankenstein Monster makeup to Chaney’s son, Lon Ralph. Lon, Jr., was a talented makeup artist in his own right, but chose to act because he said it was more fun.]

Sure, Lugosi is cool to him, decreeing that Chaney’s drinking on the set is unprofessional, and still nursing a grudge over Lon’s casting as the vampire in SON OF DRACULA. [4] But Chaney gets even with him by sarcastically calling him “Pop.”

Then, LaVigne’s Wolfman makeup is certainly more comfortable to wear—a definite improvement over Pierce’s approach, which Chaney claims has scarred his face. The streamlined process and added comfort are especially important, given that there are four Wolfman scenes in the script—the most ever.

True, Chaney complains to the press that he loses eight pounds a day because he can’t eat with the makeup on, but acknowledges that he gains most of it back at dinner. But the transformation sequences still take forever; a full-on barefaced-to-hirsute scene requires six makeup changes and 14 hours—mercifully done over two shooting days on Stage Six. [5] When not in full Wolfman mode, Lon is free to join the pie fights and the other antics.

Monday, March 15, 1948. Glenn Strange breaks his ankle.

Like Chaney, Strange has benefitted from Westmore’s simplified makeup approach. Getting full-on Frankenstein Monster now takes only about an hour. Jack Kevan has even made the footwear more palatable—the Monster’s former 13-pound asphalt spreader boots have been replaced by 4-inch elevators made of cork. While the actor is grateful for the comfort, the new boots are awkward—he’s tripped over cables more than once.

He’s tossing Aubert’s stunt double Helen Thurston out of a laboratory window when Thurston’s safety wire malfunctions; she suddenly comes swinging right back at him. Attempting to catch her, Strange trips in his cork boots…and just like that, the production is about to lose three more days.

That is, until Chaney hears.

“I’ll put the makeup on,” he offers. “I’ll do it.”

“Just as happy as he could be to do it,” Barton beams.

Chaney suits up the very next day, throws Thurston through the window, and earns the gratitude of everyone concerned. [6]

[Above: Chaney, subbing for Glenn Strange, tosses stunt legend Helen Thurston out the prop window in Dr. Mornay’s laboratory.]

Still, he has nagging doubts about how the film is utilizing The Wolfman.

To begin with, Chaney notices that Strange’s Monster is generally treated with dignity. Aside from it bit or two during the climax, any laughs Strange generates are generally due to the comic reactions surrounding him.

And Dracula, too, is treated with care. The script includes ripe lines that are delivered by Lugosi with just the right ironic touch.

“There is no burlesque for me,” Lugosi will explain. “All I have to do is frighten the boys, a perfectly appropriate activity. My trademark will be unblemished.”

But there is burlesque for The Wolfman.

As previously noted, there are four Wolfman sequences in the picture. The first—wherein The Wolfman rips up an armchair—is decently handled, effectively expanding the action as written in the script for the better.

In the next, however, The Wolfman attempts to attack Costello while they’re locked together in a hotel room. Typically, Costello goes off script. As a result, The Wolfman is so inept that he can’t get the job done.

The third scene is the worst. As written, The Wolfman’s menace isn’t truly diminished:

132 CLOSE SHOT – WILBUR

ON SOUNDTRACK we can hear Talbot’s heavy breathing.

WILBUR

(still looking o.s.)

Quiet……

132 CONTINUED

With his hand he reaches back to push Chick. He comes in contact with the Wolf Man’s face.

WILBUR

(as he turns)

What’d you put your mask on for? No wonder you can’t breathe.

But at this moment the moon has risen sufficiently to cast its light fully on Talbot who is now completely the Wolf Man.

133 CLOSEUP – THE WOLF MAN

He bares his fangs.

134 MED. SHOT – WILBUR AND THE WOLF MAN

WILBUR

(wide-eyed – pointing)

Why, Chick – what big teeth you have!

With a vicious snarl and a snap like a steel trap, the Wolf Man lunges towards Wilbur. Wilbur yanks back his hand, turns, and runs like mad, with the Wolf Man in hot pursuit.

135 CLOSE PAN SHOT – WILBUR

He dashes right into a heavy bush, picks it up and carries it along with him.

136 MED. SHOT – WOLF MAN

As he rages through the forest. [SCENE ENDS].

The action in the finished film, however, is much different.

Wildly expanding on the mild slapstick in the screenplay, Costello repeatedly punches and kicks the hairy, inexplicably clumsy beast stalking him in the woods, believing it to be Abbott in a mask; this completely destroys any fear Chaney might generate.

And though his final scenes—which involve chasing Dracula—are handled more realistically [7], the overall impression the film makes is that The Wolfman is a clown.

[Above: Wild ad-libs by Costello turned The Wolfman into a clown, at least as far as Chaney was concerned. The scene in the woods where Wilbur gets away with kicking the heretofore vicious monster in the butt was the nadir for Lon.]

“Abbott and Costello ruined the horror films,” Chaney will lament years later. “They made buffoons out of the monsters.”

They certainly messed with Chaney’s baby.

Tuesday, March 2, 1948. Barton is shooting at the concrete tank beyond the Phantom Stage. Chaney, Abbott, Costello, and Randolph are working.

Meanwhile, young Ron Chaney is causing trouble during rush hour.

Ron is a dark-haired, blue-eyed charmer, six-feet tall, with a devilishly compelling smile. But he also has a tendency to live on the edge.

Traffic is horribly backed up for blocks on the Hollywood Freeway. Police are about to arrest 17-year-old Ron and his buddy Jack A. Arbuckle, 21.

The charge? Assault with a deadly weapon.

The full story of Ron and Jack’s beer-fueled joyride is told in my book CHANEY’S BABY, but suffice it to say here that Ron and Arbuckle are taken into custody. They deny any wrongdoing. When questioned at the station, Ron gives his address as 12750 Hortense Street, North Hollywood—Chaney’s house.

Arbuckle ends up in jail. Ron is sent to juvenile hall.

On Wednesday, March 3, The Los Angeles Times reports that Ron is Chaney’s son. Chaney is back at work—they’re shooting at the concrete tank again—but he can’t be happy. This is a personal crisis. And no actor—or family—needs this kind of publicity.

[Above: Emile LaVigne makes up Chaney, Jr. with the help—at least for the picture—of Lon Ralph and Ron. Ron, a handsome free spirit with a wild side, will soon be causing his dad and stepmom a great deal of angst.]

Chaney and Patsy’s reaction to Ron’s behavior—as well as Dorothy’s—is characteristically kept private. But it doesn’t take a genius to guess that things can’t be good over at the homestead. And Universal execs in the know will later describe Chaney as being “preoccupied” during shooting.

When his father attempts suicide less than two months later, Ron tells the cops it was triggered by a “family argument.” Can Ron’s continued misbehavior—and perhaps his very presence in their house—be the source of tension between Chaney and Patsy?

No one has ever been able to confirm it. Patsy, Chaney’s agent, and his attorney will all attempt to walk back Ron’s comments. Under the circumstances, this is understandable.

It’s also possible that the mistreatment of Chaney’s trademark character in the film adds to his despair.

Whatever the case may be, there is no denying that on the night of April 22, 1948, Lon Chaney Jr. decides that life is no longer worth living. He comes very close to never seeing the film…or anything else ever again. [8]

Monday, March 22, 1948. Chaney—no doubt, still brooding over his son’s legal troubles—endures an almost 12-hour shoot wherein Talbot transforms into The Wolfman in the woods. When he leaves at 7:50 PM, he’s done with the film.

Friday, March 26. Production wraps up on what will be released as BUD ABBOTT LOU COSTELLO MEET FRANKENSTEIN. [9] The movie will rake in $3.2 million, which is a bit more than $412 million at this writing—a sizable hit.

Chaney gets third billing as “Lon Chaney.”

Publicly, according to The Oakland Tribune, Chaney has made peace with the dropping of “Jr.” by now:

“Sons and daughters of filmdom’s great have made a name of their own—and all but a few have now dropped the ‘Jr.’ after their names. The latest to do this is the son of Lon Chaney. From now on he will be known as plain Lon Chaney. The son of one of the screen’s all-time great artists, Lon’s late father died in 1930.”

Privately—though he’s no longer known as Creighton—he’ll never fully embrace the idea.

“I am most proud of the name Lon Chaney, because it was my father’s, and he was something to be proud of,” he’ll say in 1969. “I am not so proud of Lon Chaney, Jr. because they had to starve me to make me take this name. Any ability that I might have had is there. The name didn’t change it, but it certainly changed the income. So, Junior is a thing like a stick on my shoulder that I’d like to knock off, and I’d be happier without.”

ABBOTT AND COSTELLO MEET FRANKENSTEIN is a classic film that holds up marvelously today. But for Chaney, it was certainly another stick he would have liked to knock off.

NOTES

[1] The ad, entitled “He Ruled a Raw Frontier,” features a cartoon version of Chaney on the set of ALBUQUERQUE endorsing the product: “Trim Hair Tonic gives you the best looking hair by far!” It can be found in the archives of The San Francisco Examiner.

[2] According to Bob Thomas, Costello had resented Abbott since 1937 because he’d had to bribe Abbott with a bigger salary cut in order to convince him to play Atlantic City. As it turned out, the Atlantic City gigs really broke the act. In 1942—never one to forget a slight—Costello demanded a sixty-forty split in his favor, plus a change in billing to “Costello and Abbott.” An enraged Abbott agreed to the split, but not the billing. Universal backed him, and, supposedly, Costello never forgave either of them.

[3] In the final draft, The Mummy and The Son of Dracula are axed, and The Invisible Man is reduced to a bit.

[4] “I think the only person Lugosi ever disliked was Lon Chaney Jr.,” Don Marlowe, Lugosi’s agent, said (Lenning, p. 363). Yet Lugosi is a heavy drinker himself, as Gregory William Mank explains in It’s Alive: “Lugosi, whose professional ethics were far too high for him to even consider sipping his beloved brew of Scotch and beer during soundstage hours, consequently had strong feelings about his flask-brandishing co-star.” Sadly, Lugosi is also addicted to narcotics, due to “a medical gaffe in 1944” (Mank). Regarding his resentment of Chaney’s casting in Son of Dracula, Arthur Lennig in The Immortal Count states, “Lugosi was astounded to hear that Universal did not even consider him for what had been for fifteen years his most noteworthy role, but instead chose the painfully miscast Chaney. He was not only hurt; he was enraged.”

[5] Unfortunately for Chaney, the entire transformation will have to be reshot on March 13, resulting in a more than 12-hour day for him; LaVigne notes that he was a little wary of applying glue all over Chaney after the actor had been drinking.

[6] Unfortunately, Thurston catches some shards of fake glass in her eyes and has to go to the hospital. Universal ups her pay for the job to $300 (from $55).

[7] The scenes are partially handled by doubles: Walter DePalma for Chaney, Bud Wolfe for Lugosi.

[8] I cover his suicide attempt in detail in CHANEY’S BABY.

[9] This is actually the title as it appears onscreen. Of course, the film will come to be known as ABBOTT AND COSTELLO MEET FRANKENSTEIN—the title Universal announces on March 1.

SOURCES

“Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein File, The. Part 1.” Abbott and Costello Quarterly, #53. 2008. Print.

“Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein File, The. Part 4.” Abbott and Costello Quarterly, #56. 2008. Print.

Brunas, Michael, John Brunas, and Tom Weaver. Universal Horrors: The Studio’s Classic Films, 1931-1946. Jefferson NC: McFarland & Company Inc., 1990. Print.

“Bud Abbott Lou Costello Meet Frankenstein.” AFI Catalog. www.afi.com. Web.

“California, County Marriages, 1850-1952 Database.” www.familysearch.org. Web.

Churchill, Reba and Bonnie. “Hollywood Diary.” Valley Times. Feb. 21, 1948, p. 13. Print.

Fleck, Bill. CHANEY’S BABY. Wurtsboro, NY: Just Pay the Ransom Publishing, 2021. Print.

“Freeway Free-For-All Jams Cars for Blocks.” Los Angeles Times, The. March 3, 1948, p. 2. Print.

Gourley, Jack and Gary Dorst. “A Man, A Myth, and Many Monsters.” Filmfax. May 1990. Print.

“He Ruled a Raw Frontier.” San Francisco Examiner, The. Feb. 15, 1948, p. 26. Print.

Hopper, Hedda. “Looking at Hollywood.” Los Angeles Times, The. Jan. 10, 1948, p. 7. Print.

Lennig, Arthur. The Immortal Count. University Press of Kentucky, 2003. Print.

Johnson, Erskine. “Bing Isn’t Bothered About Little Things Like Toupees.” Ventura County Star-Free Press. June 8, 1948, p. 8. Print.

“Juniors Make Good in Own Film Careers.” Oakland Tribune. March 18, 1948, p. 30. Print.

“Lenore Aubert Joins Dracula Entourage.” Los Angeles Times, The. Jan. 26, 1948, p. 11. Print.

Lompoc Record. July 8, 1948, p. 8. Print.

Mallory, Michael. Universal Studios Monsters: A Legacy of Horror. New York: Universe Publishing, 2009. Print.

Mank, Gregory William. It’s Alive. San Diego/New York: A.S. Barnes & Company, Inc, 1941.

McCelland, Doug. Golden Age of B Movies, The. Bonanza Books, 1978. Print.

Mulholland, Jim. Abbott and Costello Book, The. New York: Warner Books, 1975. Print.

Othman, Frederick C. “Hollywood Film Shop.” Chico Record. October 25, 1942, p. 2. Print.

Riley, Philip J., ed. Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein: The Original Shooting Script. Absecon, NJ: MagicImage Filmbooks, 1990. Print.

Smith, Don G. Lon Chaney, Jr.: Horror Film Star, 1906-1973. Jefferson, NC: MacFarland & Company, 1996. Print.

“Son of Actor Lon Chaney Being Held.” Wilmington Daily Press Journal. March 3, 1948, p. 10. Print.

“Steinbeck Play at Lobero Theater.” Santa Maria Times. July 12, 1948, p. 5. Print.

Thomas, Bob. Bud & Lou. Philadelphia/New York: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1977. Print.

Thomas, Bob. “Hollywood.” News-Pilot. March 3, 1948, p. 2. Print.

Thomas, Bob. “Hollywood.” Johnson City Press, March 5, 1948, p. 5. Print.

“Two Held After Fight on Cahuenga Freeway.” Valley Times. March 3, 1948, p. 1. Print.

“Weatherman Offers Hope for Downpour. Los Angeles Times, The. Feb. 5, 1948, p. 1. Print.

Note: The pictures used herein are intended for educational purposes only. I do not own the copyrights, nor do I make any money from this website.