Classic Horror Behind the Scenes: Roy William Neill: An Appreciation

Roy William Neill will never garner the accolades lauded upon James Whale or Tod Browning. But Neill’s contributions to horror and mystery films of the 1930s and 1940s deserve praise nonetheless.

By Bill Fleck, author of the Rondo-nominated book CHANEY’S BABY, available here.

Check out other articles on my Rondo-nominated website by clicking here.

Did you know? Two-time Rondo-Award winning filmmaker Thomas Hamilton is in the process of making THE CHANEYS: HOLLYWOOD’S HORROR DYNASTY, which is inspired by my book, CHANEY’S BABY. (I’m also a producer on the film.) If you’d like to support the project, click here and see what’s going on. Thanks!

Breaking news: This website has been nominated once again for a RONDO HATTON CLASSIC HORROR AWARD (Best Website)! Winners are decided by votes, so—if you have a second—please email “Best Website: Bill Fleck” to: taraco@aol.com by midnight on April 16, 2024. Please include your name. (Don’t worry; no information is shared or kept.) Thanks to readers like you for supporting my labors-of-love.

“It’s holding me!” Freddie Jolly gasps painfully. “Help me—help me!”

A taller, younger man wearing a shapeless black hat—and holding a lantern—stares incredulously into the darkness at the horrific scene before him, unable to believe own his eyes…

Freddie Jolly’s wrist is locked in the unbreakable iron grip…of a corpse.

“Alive!” the astonished younger man whispers, still not entirely comprehending exactly what’s happening…

It seemed like a great idea to Freddie Jolly when he’d first heard that Lawrence Stewart Talbot, heir to the Talbot estate overlooking Llanwelly Village in Wales, had been buried four years ago—after being killed in a tragic accident—with a watch, a ring, and money in his pockets.

“Everybody in the village knows about it!” Freddie crows to his latest partner in crime.

Freddie, 53, is no stranger to regional police agencies. A small-time hustler and ne’er-do-well, the scrubby, mustachioed Freddie has even seen the inside of a Llanwelly jail cell for vagrancy.

So, when Freddie lays out his plan to rob Talbot’s grave of what he’s sure will be easy—but profitable—pickings, he’s absolutely sure that nothing will go wrong.

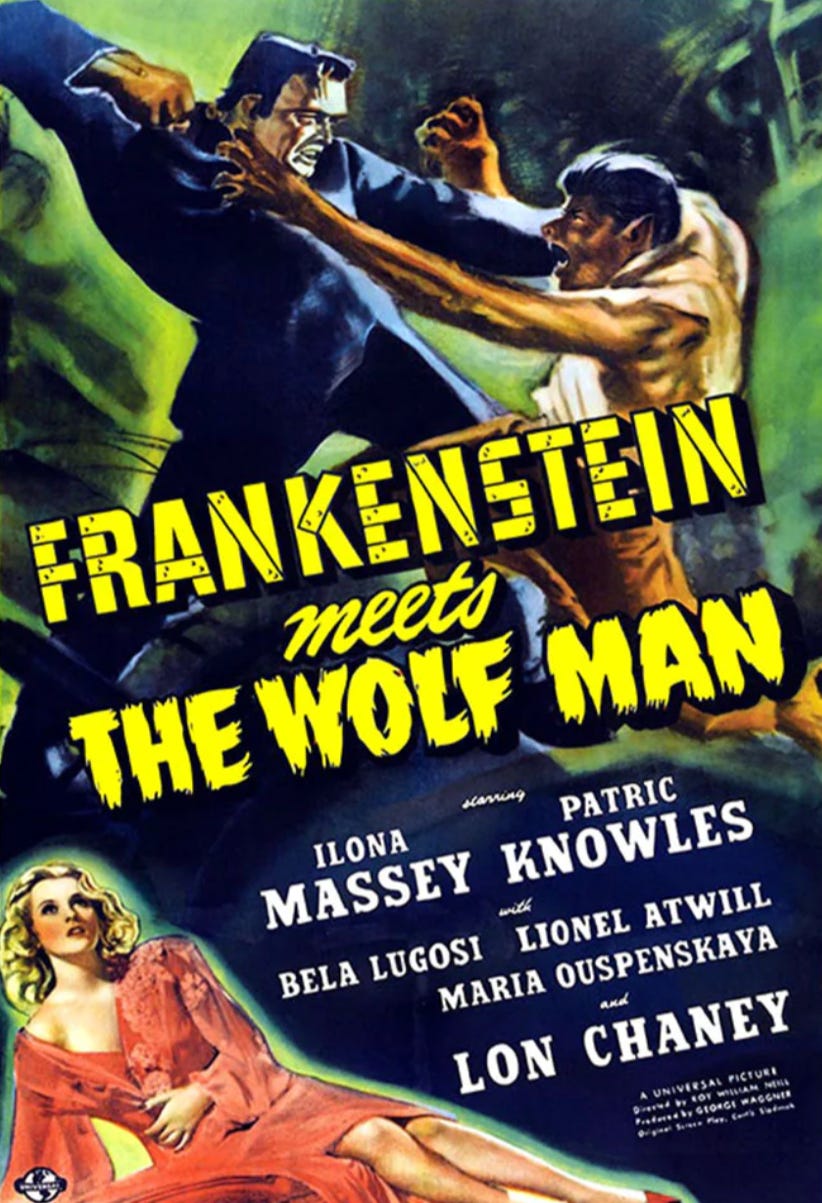

[Above: Freddie Jolly and his unnamed accomplice head toward the Talbot mausoleum, intending to steal the watch, ring, and money off of Lawrence Talbot’s corpse in the opening sequence of FRANKENSTEIN MEETS THE WOLF MAN (1943). The scene is often cited as being the best opening in Classic Horror.]

The night of the operation begins perfectly under the eerie glow of the full moon. Freddie knows that no one has died recently in Llanwelly, and that superstitious villagers are inclined to stay away from the graveyard under the best of circumstances. He’s certain that nobody will be present in that graveyard to foil his plans.

Coming around the bend in the blustery wind, and entering the cemetery gate, Freddie sees right away that he is correct: his only company is the younger man in the shapeless hat…and two crows that seemingly have nothing better to do than to caw at them.

Crossing the grounds, a suddenly annoyed Freddie notices that his partner seems to be hesitating.

Is he thinking of turning back?

Freddie knows that the man is scared—in spite of his relative youth and large size, he’s tightly clutching an iron pry bar, which is roughly as tall as Freddie himself.

Looking to redirect the situation, Freddie angrily grabs his partner’s sleeve and moves him forward to the Talbot mausoleum, where they handily hoist themselves up and wriggle in through a tight opening above the locked door.

The light of the moon streaming through the iron-laced window bathes the interior, but Freddie still needs a lantern to read the names of the interred.

John Talbot. Lawrence and Anne Talbot. Martin Talbot. Elizabeth Talbot. And then—at the center of the room—jackpot:

LAWRENCE STEWART TALBOT / WHO DIED AT THE YOUTHFUL AGE OF THIRTY ONE / R.I.P.

“That’s it!” Freddie declares. “Give me the chisel!”

“Suppose they didn’t bury him with the money on him…?” his nervous companion asks, handing over the tool.

Freddie reminds him—yet again—that everyone knows about the money, the watch, and the ring.

“It’s a sin to bury good money,” the taller man opines, “when it could help people.”

As he begins to pry up the lid, Freddie knows exactly who this money will help.

“What do you suppose it’ll look like, after so many years?” the tall thief stammers.

Crikey, is this guy is a bundle of nerves…

“Just bones,” Freddie tries in a reassuring tone, “and an empty skull. Watch the lantern!”

A raw, yawning creak in the shadows indicates that the seal on the coffin lid has finally been breached. Freddie and friend work the heavy cover off the top and let it crash to the floor. Immediately, Freddie’s animal brain tells him that something is off here…

“Get me the light…”

The lantern reveals a curious sight. Piled on top of the body—which, unexpectedly, is not “just bones and an empty skull”—are the dried remains of a peculiar plant. A plant that Freddie knows very well.

“Wolfbane…” [1]

“Wolfbane?” his companion asks, obviously confused.

“Yeah,” Freddie says.

And then—as if under a spell—he recites the ancient poem:

“Even a man who is pure at heart, and says his prayers by night, may become a wolf when the wolfbane blooms, and the moon is full and bright.”

It’s not lost on either of these thieves that the moon is full and bright this evening…

And then, as if by some terrible magic, the moon’s powerful rays shine on the corpse, revealing the dark-suited Talbot in repose…the skin shrunken back from his nails, his now-gaunt face allowing a short beard to poke through, his brows somehow expressing worry over his closed eyes…

“It looks like he’s asleep,” the tall thief says.

But Freddie is impatient.

“Let’s get on with it,” he snaps. “First, the ring.”

He reaches into the coffin, and quickly attempts to twist the ornament off of Talbot’s finger.

“We won’t have to worry for a long time,” he whispers.

But something about Talbot’s hand bothers the tall thief. The fingers seem to be, well, supple…

“I thought the dead were stiff—?” he blurts out.

“Shut up!”

And then the ring comes loose. Freddie triumphantly holds it up to the light, rapturously examining his new treasure with a gleam in his eye.

“Gold!” he exclaims with joy.

So distracted is Freddie by his ill-gotten riches that he doesn’t notice the slowly-moving left hand of the corpse impossibly inching towards him. By the time it clamps down on his wrist in a certain death-grip, there is nothing to be done…

Freddie drops the ring; it clacks on the concrete floor, no longer important. It’s not material wealth that Freddie wants now—he’s fighting for his life, and instantly, he realizes it. But so strong is the grip on this dead man that he knows he can’t break free by himself. It’s now that he begs the tall thief for help.

[Above: Revived by the moonlight, lycanthrope Larry Talbot traps Freddie in a death grip. The doomed Freddie begs his horrified partner in crime for help.]

That help will not be forthcoming.

Scared to within an inch of his life—and still unable to comprehend exactly what is happening before him—every fiber of his body tells the tall thief to run. He drops the lantern, which immediately bursts into flames. He’s scrambling out of the tomb, away from certain death, when the doomed Freddie desperately calls out to him:

“Don’t leave me!”

But there’s no going back. The tall thief is gone, plunging and stumbling through the graveyard with no intention of ever setting foot back there.

And he’ll never tell anyone anything about what has happened here tonight.

Freddie is left to face the growing fire—and the horror of whatever this impossibly powerful corpse has planned for him in that desolate graveyard—alone…

This is the wild beginning to FRANKENSTEIN MEETS THE WOLF MAN (1943)—a scene so riveting that many Universal Monster fans cite it as being the single most effective opening scene in Classic Horror history.

And there is no denying that it is extremely effective. Kudos are certainly due for art director John Goodman’s sets, George Robinson’s moody photography, the fine editing of Edward Curtiss, Hans J. Salter’s impressively mysterious music, plus the acting of Ceril Delevanti (Freddie) and Tom Stevenson (the Tall Thief).

But mixing these ingredients and making them into a perfect stew is none other than director Roy William Neill.

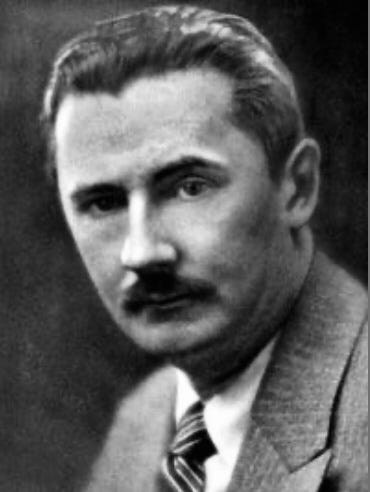

[Above: Director Roy William Neill, best known to Monster Kids for THE BLACK ROOM (1935), the Sherlock Holmes series with Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce, and FRANKENSTEIN MEETS THE WOLF MAN.]

Neill—as two-time Rondo-winning filmmaker Thomas Hamilton explains—was, “a fantastic director who went on to do those great Sherlock Holmes films. That’s another thing that comes up when you start looking at these films. There are a few directors who were really important. The obvious one, of course, is James Whale, and then you’ve got Tod Browning. But you also have people like Roy William Neill and Rowland V. Lee, who were really expert craftsmen—and they didn’t necessarily work constantly in horror. But everything they did in that field was well above normal.”

FRANKENSTEIN MEETS THE WOLF MAN is a special film to me. Thanks to ABBOTT AND COSTELLO MEET FRANKENSTEIN (1948), I’d been a Wolf Man fan since third grade. And thanks to Robert F. Moss’s book KARLOFF AND COMPANY, I was a pretty well-educated Monster Kid by fifth.

Or so I thought.

True, I knew that Lon Chaney, Jr. was never Moss’s favorite actor—his comments on Chaney in his book more than indicated that.

What I didn’t know was that Moss arbitrarily decided not to write about certain films in the Universal canon in that book. And when I say “decided not to write” about them, I don’t mean that he mentioned them and tossed off a line or two about why they weren’t worth examining. I mean “decided not to write” about them as in “pretending they didn’t exist.”

As such, Moss listed THE WOLF MAN, HOUSE OF FRANKENSTEIN, HOUSE OF DRACULA, and A&C MEET FRANK as the films in which Chaney played the Wolf Man.

He made no mention of FRANKENSTEIN MEETS THE WOLF MAN at all. None. Zero. Nada.

So…imagine my surprise when WWOR-TV (channel 9) ran the film instead of the Mummy opus I was expecting since it had been announced in TV GUIDE.

It was a random trade that had me over the moon.

Of course, over the years, my childhood monster obsession has become, well, a getting-to-geezer-age monster obsession. And part of the fun of writing this blog is researching the people who made the films we Monster Kids still love.

That’s why, this month, we’ll examine the somewhat mysterious but multi-talented Roy William Neill.

Mysterious, because much of the claims made about him are difficult, if not impossible, to verify.

And multi-talented for reasons that will become obvious.

Sunday, September 4, 1887. Roland de Gostrie (or de Gastrie)—later known as Roy William Neill—is born on board a ship anchored in Ireland’s Dublin Bay. His Irish father is also the captain of the ship, which is under an American registry.

“Under our laws,” columnist Virginia Wright will eventually report, “that makes him an American.”

Neill—who will always think of himself as an American—obviously agrees. Still, being considered a British subject under English law will eventually be of professional use to him, since he will later spend years in England working on films.

But before that happens, Neill graduates from St. Mary’s College of California, a private Catholic school located in Moraga. The authors of UNIVERSAL HORRORS say that he then serves “a stint as a war correspondent.” Bitten by the acting bug, he begins touring in stock companies. [2] He also dabbles in playwrighting.

By 1906, the 18-to-19-year-old Neill is back in California, where he is a director at the Alcazar Theater in San Francisco.

“It was at this theatre that he met Lon Chaney, Sr.,” Luis Rosado will allege, “that great artist whose successes in filmland were too numerous to mention, and who appeared in many of the productions that Neill directed for that theater.” [3]

By 1915, Neill is working for Thomas Ince in films.

“He was assistant cameraman and assistant director on CIVILIZATION,” Wright notes. “He was even an actor in that production, playing the boy who was shot by a firing squad—a squad, incidentally, which included John Gilbert and Jean Hersholt in its ranks.”

It’s alleged by the Associated Press that—somehow or other around this time—Neill serves as a pilot in World War I. [4] What’s certain is that, by November 1917, he’s directing films himself.

According to Wright, Neill moves up to “the executive class” when he invests in California Studios, “the studio which stood where Columbia stands today.” But it’s the feature film TOILERS OF THE SEA that really puts him on the map.

Originally intended for director Rex Evans, Neill ends up producing and directing the film on location in Italy. Based on a novel by Victor Hugo, the story is a melodrama filled with backstabbing and betrayal that literally ends in a shipwreck.

Neill initially intends to have that ship wrecked in spectacular fashion by a giant octopus. But the largest one in captivity—on display in a tank in Naples—turns out to be a disappointment.

“[N]o amount of faking could make it appear that the creature could wreck a ship,” Wright explains. “Neill was stumped for the moment…”

Then, on June 6, 1923, Mount Etna erupts. Neill and one of his cameramen—who supposedly also works for Pathe News—have a brainwave. They decide to rush over to the east coast of Sicily, shoot stunning footage of the eruption, and splice that in as the cause of the climatic shipwreck.

[Above: Mt. Etna in Sicily. Neill, shooting Victor Hugo’s TOILERS OF THE SEA in Italy, intended for a giant octopus to cause the film’s climatic shipwreck. When those plans fell through, Neill was stumped…until Mt. Etna erupted. Neill used dramatic footage from the eruption to complete the sequence.]

Shortly thereafter, Wright claims that Neill is back in the United States as “director-general for Technicolor, in charge of Metro’s ‘Great Events’ series.” This may or may not be true, but what is certain is that Neill makes THE VIKING (1929), the first feature film in Technicolor’s Process 3. Viewed today, THE VIKING is still strikingly gorgeous.

Neill soon lands at Columbia, where he makes an impression on then-sound man—and future director—Edward Bernds.

“In appearance, Neill was dark, had jet black hair and plenty of it,” Bernds is quoted in UNIVERSAL HORRORS. “Roy’s speech was that of an educated Irishman, somewhat British-sounding, but with just a hint of the Irish lilt or brogue. Roy had some fingers missing on one hand, I’m sure it was his right hand. Some of the crew called him ‘Rocking Chair’ Neill. The prop man had to have a rocking chair on the set for him when he directed. Eventually, they fixed up a director’s chair with rockers, with a big canvas pocket hanging onto one arm of the chair to hold the director’s script.”

By the time he makes THE BLACK ROOM (1935) with Boris Karloff, “Rocking Chair” has directed more than seventy films.

Of course, THE BLACK ROOM holds a special place in the hearts of Monster Kids. To begin with, Karloff is fantastic in the film where he performs—to paraphrase film historian Greg Mank—a triple role: the kind Anton, his evil twin Gregor who murders him, and then Gregor pretending to be Anton!

Neill handles the scenes wherein the twins appear together expertly, through the use of double exposure, stand-ins, and clever editing by Richard Cahoon. Moreover, the pace of the film—and the excellent use of light and shadow—go a long way toward selling the melodrama. THE BLACK ROOM is a film worth seeing to this day.

[Above: One of Neill’s triumphs at Columbia: Boris Karloff playing twins in THE BLACK ROOM (1935). Neill deftly handled the scenes wherein the evil Gregor (L) and the kindly Anton (R) interact through the use of double exposure, stand-ins, and clever editing.]

Shortly after, Neill, his wife Betty MacGlaglen, and their two daughters relocate to London. Once settled in, Neill begins work as a producer-director for Warner Brothers.

“The fact that he had been christened Roland de Gastrie in English water simplified matters for him there,” Wright asserts. “Being considered a British subject, he didn’t have to bother with working permits and visas.”

One of the films Neill is involved with over the pond is DOCTOR SYN (1937), the last to feature George Arliss. He also gets back into playwrighting.

But life in England is shattered by the onset of World War II. Figuring that it’s better to be safe than sorry, the Neill family returns to America. One of Roy’s stories—“Two Tickets to London”—catches the attention of Universal executives.

Friday, June 5, 1942. Virginia Wright has news.

“Hollywood, which used to be known as the land of ‘too many cooks,’ suddenly is beginning to value the gentleman of double and triple ‘threat’…” she writes. “The studio which seems to have been won over on a wholesale basis to this new idea is Universal. The names of Henry Koster, Roy William Neill, Howard Hawks and Oliver Drake have been added to its standing list of double and triple threaters, which includes Bruce Manning, Gregory LaCava, George Waggner, Charles Boyer, and Dwight Taylor.”

Neill’s first assignment? EYES OF THE UNDERWORLD, a crime drama/prototype film noir featuring Richard Dix, Wendy Barrie, and Lon Chaney, Jr. Shooting begins on March 23, 1942.

Meanwhile, the Neill family settles in at 7827 Woodrow Wilson Drive in Los Angeles. They begin preparations for their daughter Barbara’s wedding to Lt. Leslie L. Taylor—“stationed with an armored force division”—at the Church of the Blessed Sacrament on July 19.

It’s during this time that Neill receives one of the assignments for which he remains famous.

As all Monster Kids know, Universal has recently gotten the rights to Sherlock Holmes from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s estate for $300,000—the equivalent of about $5.7 million at this writing. The rights are granted for seven years, and include the use of 21 of Conan Doyle’s stories. The studio has wasted no time in securing Basil Rathbone (more on Basil here) and Nigel Bruce, who had starred as Holmes and Watson in two successful period pictures for 20th Century Fox in 1939.

Of course, as all Monster Kids know as well, Universal has made the decision to set the detective’s adventures in contemporary times, ostensibly because costume pictures aren’t doing well in the ugly grip of the war. As such, the first Universal Holmes film—SHERLOCK HOLMES AND THE VOICE OF TERROR—features Holmes and Watson battling the Nazis.

[Above: Roy “Mousey” Neill. Though it’s claimed that he had no sense of humor, he was still a nice guy with a vision for film and a lively style.]

VOICE OF TERROR is directed by John Rawlins, who—in the opinion of the authors of UNIVERSAL HORRORS—“does a polished job. Visually, the film is a distant cousin of the others in the series, mostly because of Rawlins’ fondness for long, intimate close-ups” (p. 315).

But the follow-up—initially titled SHERLOCK HOLMES FIGHTS BACK—is given to Neill.

The authors of UNIVERSAL MONSTERS think they know why:

“Neill, affectionally called ‘Mousey’ by his coworkers, was the ideal choice as director of the Holmes series with his sure eye for atmosphere and his crisp, straightforward style. He worked well with modest budgets and conveyed a convincingly British tone.”

Basil Rathbone, for one, agrees. For Basil, shooting the series—at least early on—is a pleasure.

“None of those pictures made at Universal took more than seventeen days,” he’ll explain in a lecture later on. “We never started shooting before nine—today it’s 8:30 or even 8 o’clock—and worked until six. No night work unless required by the script. At four o’clock there was half an hour for tea. This mood—the whole of the making of the pictures—they had a sense of ‘family.’ We all got along very well together. We had our little differences from time to time, but the one lovely character of them all was our dear friend, the director.

“We loved Roy Neill,” Rathbone continues. “He was mousey, a little guy. A little guy and as sweet as they come. But a damn good disciplinarian. We didn’t disobey orders on set. We were always on time and we always knew our lives. It was thoroughly professional.”

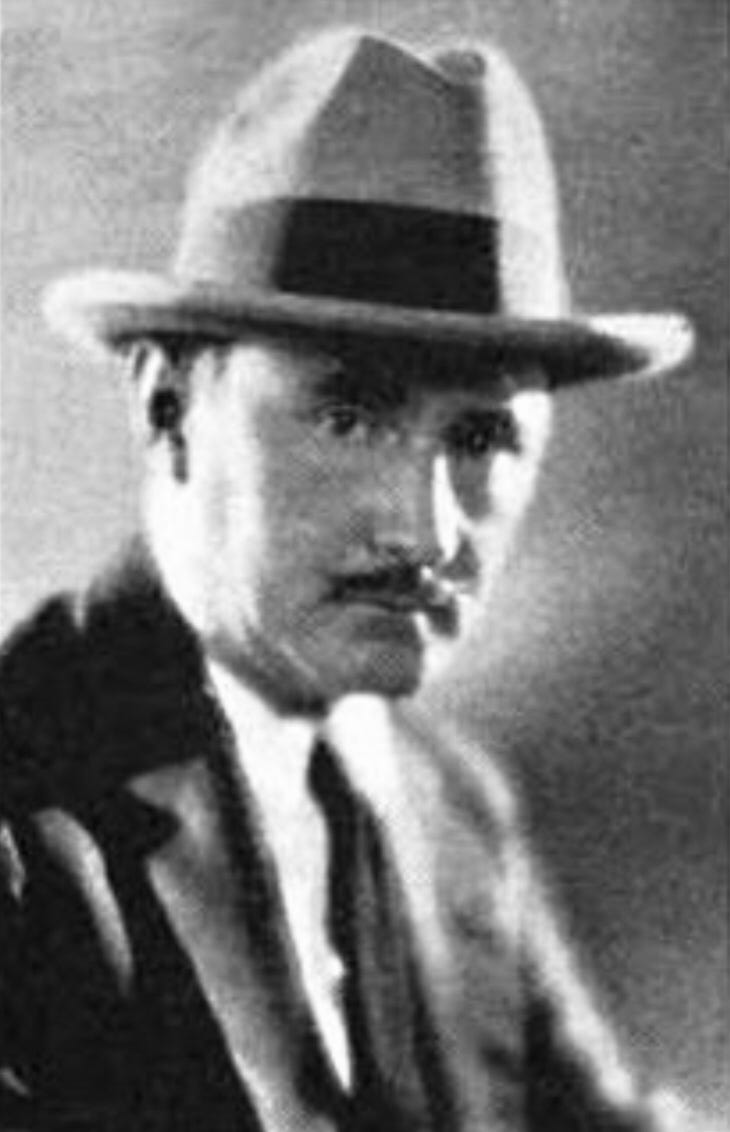

[Above: Neill’s first Holmes film, SHERLOCK HOLMES AND THE SECRET WEAPON, pits Holmes (Rathbone) against his arch-enemy Professor Moriarty (Lionel Atwill). Neill directed 11 of the 12 Universal Holmes series.]

By the time the film is premiered in New York, the title has been changed to SHERLOCK HOLMES AND THE SECRET WEAPON. And Neill has already shot the follow-up, SHERLOCK HOLMES IN WASHINGTON.

And then, he gets his next assignment…

“The latest adaptation of the ‘Boy Meets Girl’ idea is ‘Wolf Man Meets Frankenstein,’ a dainty little blood-curdler which Universal is whipping up,” columnist James Francis Crow announces on October 8, 1942.

“Lon Chaney Jr. will be the wolf man, of course. And today the Universal executives were studying a plan whereby Chaney also would play—in the same film—the role of the Frankenstein monster which he inherited from Boris Karloff.

“It is a problem for George Waggner the producer, for Roy William Neill the director, and especially for Jack Pierce the make-up man.

“If they succeed in solving it, one day you will see Lon Chaney Jr. strangling each other.”

The origins of the production are interesting.

As we’ve seen, the project actually starts as THE WOLF MAN MEETS FRANKENSTEIN, since the picture as conceived is a sequel to THE WOLF MAN (1941). WOLF MAN screenwriter Curt Siodmak is given the task of bringing the Titans of Terror together.

This isn’t going to be easy.

“The Wolf Man’s head had been bashed in by his own father in a Welsh forest,” notes THE SATURDAY EVENING POST on May 23. “Frankenstein’s monster had last been seen crushed under huge timbers in a burning house somewhere in the Balkans.”

Characteristically, Siodmak is frustrated by the assignment…at first.

“Whipped cream is good and herring is good,” he complains, “so they think they should be better together.”

But then, he gets a brainwave: the Wolf Man wants to die. The Monster wants to live. What if the secrets in Dr. Frankenstein’s notebook can help each of them get what they desire?

Add to this the fact that Chaney is the last guy to have played both parts. As we’ve seen, this gives producer George Waggner a brainwave of his own.

Why don’t we have Chaney play the Wolf Man and The Monster in this one? he asks Neill. We can use doubles and stunt men. Think of the publicity!

Neill begins planning. After all, he’s proven his expertise at handling such scenes in THE BLACK ROOM. But it turns out the trickery involved will cost too much. Plus, does anybody really want to deal with Chaney—who can be prickly—in two heavy makeups? The studio claims in the press that playing both parts in such uncomfortable get-ups would be “too excessive” on Chaney.

As such, The Monster is offered to Bela Lugosi…which makes some sense, in that Lugosi’s character’s brain was deposited into The Monster’s skull at the end of GHOST. The part as written for MEETS portrays The Monster as blind and weak, but able to speak, so Lugosi develops a variation of his Ygor voice for the dialogue.

Neill starts shooting on Monday, October 12, 1942.

Soon, the U.P.’s Frederick C. Othman catches up with Chaney (in full Wolf Man regalia), Ilona Massey (playing Elsa), and Neill on the set one fine October day. Hanging with Chaney is his beloved German Shephard Moose, who serves as The Wolf Man’s stand in.

“Some weeks ago, as you may have read, Universal Studios scheduled a motion picture entitled ‘The Wolf Man Meets Frankenstein,’” Othman writes. “Only the boys felt there was something wrong with that name. It did not quite put across the feel of the proceedings, they said. They thought, and they thought, and they came up today with a new and final title…”

Which is, of course, FRANKENSTEIN MEETS THE WOLF MAN.

“Honest!” Othman chides. “That’s it!”

The interior sets, including the Frankenstein castle—as we’ve noted above, designed by John Goodman (assisted by Martin Obzina)—have been built at the other end of the Phantom Stage, which had been famously constructed for THE PANTOM OF THE OPERA (1925). This isn’t lost on Luis Rosado when he pays a visit.

“Strange, we thought,” he’ll write. “For here was Lon Chaney’s son making his mark in the movies—on the same stage.”

“Arriving at the Phantom Stage, where the two playboys from horror-land were carrying on under the guidance of Director Roy William Neill, we found ourselves inside the remains of the Frankenstein castle,” Rosado observes. “The structure had been burned, later swept through by a flood. The set was cold, eerie, and the wind machine did its best howling for the mood and sound technicians.”

The scene being shot on this particular day involves Lugosi and Chaney attempting to unearth Dr. Frankenstein’s records. When they appear to be missing, Chaney—as Talbot—is decidedly unhappy.

But “unhappy” is not a word that can be applied to Lon Chaney, Jr. on this shoot. For, in spite of Waggner and Neill’s concerns, Chaney is on his best behavior…even though the Wolf Man makeup has been somewhat expanded. His colleagues take notice.

“Lon Chaney is one of the nicest, sweetest people in the world,” says Ilona Massey, the Hungarian-born actress who plays Dr. Frankenstein’s daughter. “I never had any difficulty with my co-stars, but Chaney was something special.”

Under Neill’s direction, he’s also giving a marvelous performance.

“Lon played the part of Larry Talbot with a sincerity that gave that film a value of fear and pity…” Siodmak will write years later. “I knew Lon until his premature death in 1973, a tragic character who couldn’t adjust himself to life. He was the Larry Talbot in FRANKENSTEIN MEETS THE WOLF MAN., who wanted to die. In that picture, Lon played himself, which made his part frighteningly believable.”

If Siodmak is right—that Lon wants to die—Chaney almost gets his wish one day when he and Maria Ouspenskaya, reprising her Maleva role from THE WOLF MAN, are violently thrown from a horse-drawn cart. One of the wheels hits a rut, and the cart capsizes, trapping the actors underneath. Luckily, the horse stops, and Moose leaps into action, guarding Ouspenskaya from the horse’s hooves until she can be rescued.

As it turns out, Ouspenskaya and Chaney aren’t the only accident victims on the production:

· Script handler Connie Earl gets hit by an ice machine, resulting in a gash on her head.

· Stagehand Jack Ross gets nailed by a falling prop tree.

· Gaffer Max Nippell is knocked unconscious by an improperly secured beam.

It’s worse for poor Bela Lugosi. The 35-to-40-pound Monster makeup and costume cause him no end of suffering. The 60-year-old actor’s energy has been sapped to the point that he’s collapsed twice on set already.

The nadir occurs while filming close-ups of the climactic battle with the Wolf Man. In the process, Lugosi goes crashing into a stone wall and is knocked out.

All of this leads gossip columnist Erskine Johnson to ask: is Universal’s Phantom Stage jinxed?

Waggner is having none of it, though he acknowledges such rumors “add to the mystery and horror of a horror picture…

“It all started the first week of production when Miss Massey packed her bags and left her husband, Alan Curtis,” Waggner concedes. “Next came a series of illnesses which gave us a headache for a few days, and then Lugosi weakened after losing 15 pounds in three weeks. He can’t stand more than a few hours now in makeup. If he can pull through this battle scene, we’ll all feel easier.”

Off the record, it soon becomes obvious that Bela won’t be able to pull through this battle scene. Or much of anything else.

But since stunt men Eddie Parker and Gil Perkins are doubling The Monster and the Wolf Man in long shots for the battle anyway, why not just let them take over for Lugosi in other scenes as well?

With this strategy in place, Neill wraps principal photography on November 11.

[Above: The climactic fight from FRANKENSTEIN MEETS THE WOLF MAN. It’s likely stuntman Eddie Parker for Chaney on the left, and probably Gil Perkins doubling Lugosi on the right. In spite of a butchered second half, the film has come down as a minor horror classic and one of Neill’s most famous films.]

Edward Curtiss (SABOTEUR) cuts the film. Hans J. Salter does the music, incorporating leitmotifs from both THE WOLF MAN and THE GHOST OF FRANKENSTEIN. A screening is soon set up for the production staff. [8]

“All were enjoying Neill’s superbly atmospheric direction and Chaney’s better-than-usual performance,” Greg Mank writes in 1981, “until there came a scene which originally followed Talbot’s rescuing of the Monster from the ice.”

It’s the first scene featuring the talking Lugosi Monster.

Exactly who is to blame for what happens next is uncertain. Siodmak blames Lugosi, whom he claims can’t act.

“Lugosi couldn’t talk…” Siodmak explains. “They had left the dialogue I wrote for the Monster in the picture when they shot it, but with Lugosi it sounded so Hungarian funny that they had to take it out!”

Others have blamed Siodmak for writing a bunch of overly-ripe, cringeworthy lines.

No matter. The folks in the screening room are laughing hysterically. Which begs the question…

Why didn’t anyone point this out during shooting?

Edward Bernds blames it on Neill. Neill, Bernds claims, has, “absolutely no sense of humor.” So anything funny about Lugosi’s delivery has just sailed over the director’s head.

Maybe so, but nobody else on the set caught on?

No matter. Panicked, Waggner orders Curtiss to cut all of Lugosi’s dialogue.

But that’s not all.

“To make matters even worse,” Mank says, “all references to the Monster’s blindness were expunged as well. Hence, Lugosi’s stretching and groping mannerisms no longer made any sense. The damage dealt to Lugosi’s sincere but weak performance was devastating.”

FRANKENSTEIN MEETS THE WOLF MAN—sliced-and-diced second half and all—debuts in Los Angeles on February 18, 1943. VARIETY likes it, THE HOLLYWOOD REPORTER makes fun of it, and THE NEW YORK TIMES trashes it.

Rightly or wrongly, the suits blame any problems with the film on Lugosi. He won’t make a picture at the studio again. [9]

Chaney, however, comes out of this one with an enhanced reputation. It’s one of his best performances, the Wolf Man story has been treated with respect, and the film makes money. If Bela Lugosi is the fall guy, well, there’s nothing Lon can really do about it.

As for Neill, next to the Sherlock Holmes series, FRANKENSTEIN MEETS THE WOLF MAN is the film for which he is best remembered. And with good reason.

“Of the three monster rally films, FRANKENSTEIN MEETS THE WOLF MAN is easily the best,” Brunas, et al. will write. “Taking a break from the Sherlock Holmes series, the talented Roy William Neill puts forth what seems a sincere effort, injecting some mood and style into a film whose badly exploitive title and premise set it down as routine even before a frame of film was exposed…Neill puts his familiar stamp on the film. It’s atmospheric, almost noir-ish in spots, and is enhanced by good performances as well as some excellent technical credits.”

And, of course, there is that marvelous opening scene…

Neill follows up by directing at least a dozen more films, which, of course, include some of the most impressive in the Sherlock Holmes series: THE SCARLET CLAW (1944). THE PEARL OF DEATH (1944). THE HOUSE OF FEAR (1945). THE WOMAN IN GREEN (1945).

The last will be DRESSED TO KILL (1946), after which Basil Rathbone washes his hands of Holmes and Hollywood—for a while, anyway—and heads back to the New York stage.

In all, Neill has directed eleven out of the so-called Baker Street Dozen. And his last film, BLACK ANGEL (1946) is considered to be a legitimate film noir.

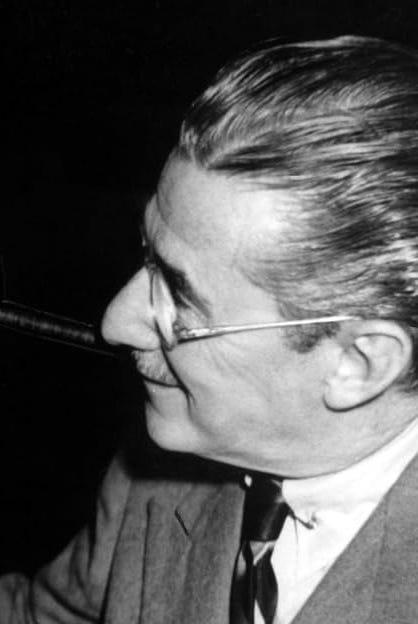

[Above: Neill late in life. Though he’s not as celebrated among Monster Kids as is James Whale, his contributions to Class Horror films are solid.]

Saturday, December 14, 1946. The end comes too soon for 59-year-old Roy William Neill.

While visiting the London home of Sidney Bracy—his nephew and associate—Neill is felled by a heart attack. Betty Neill and their two daughters are notified back in Hollywood. Services are held in London on Friday, December 20. Neill’s burial details are unknown.

If Rathbone’s reluctance isn’t enough, the death of Neill certainly puts a stop on any future plans for Sherlock Holmes at Universal. But still, those mostly excellent films remain the defining achievement of Roy William Neill’s long and varied career.

“I can see traces of the Roy Neill I knew in the Columbia days in the skillful composition and staging of his scenes, “Bernds will muse later. “I’m glad that he had a chance to exercise some of his skill, or artistry…”

So am I.

NOTES

[1] Though it’s pronounced “wolfbane” in the film (and Siodmak spells it “wolf-bane” in the script), the scientific name is Aconitum. A quick Google search reveals that, “Aconitum, also known as aconite, monkshood, wolfsbane, leopard’s bane, devil’s helmet, or blue rocket, is a genus of over 250 species of flowering plants belonging to the family Ranunculaceae.” It’s also poisonous, and exposure can cause “nausea, vomiting, severe headaches and a slowed heart beat.” Death can also result.

[2] Exactly which war is unknown. And getting into acting is perhaps the reason he changed his name, but I have no definite authority to cite on that, either. In fact, the online Encyclopedia Brittannica raises questions as to whether or not his birth story is actually true: “Sources provide conflicting information concerning Neill’s early life,” they state. “Most give his birth name as Roland de Gostrie and state that he was born on a ship—which was captained by his father—in Dublin Harbour. Others, however, claim that his birth name was Roy William Neill and that he was born in San Francisco.”

[3] This is probably a fabrication. Chaney spent most of 1906 into 1907 in Oklahoma City, OK, where his son Creighton was born on February 10, 1906. Michael F. Blake, Lon’s biographer, lists 10 theatrical appearances for Chaney in 1906-1907, all at the Delmar Gardens Theatre in Oklahoma City. The only credit Blake has for Lon at the Alcazar occurs in 1913, “Serving only as a choreographer.” Though Blake admits his list of “Chaney’s theatrical appearances is by no means a complete one,” due mostly to Chaney’s work being often uncredited at the time, I believe that the circumstances of Chaney’s life in 1906-1907 would disqualify the claim that Neill directed him at the Alcazar. See Blake, A THOUSAND FACES: LON CHANEY’S UNIQUE ARTISTRY IN MOTION PICTURES.

[4] See, for example, THE NASHUA TELEGRAPH, December 16, 1946, p. 5. Where he served—if he actually did—and for how long is a mystery. The U.S. voted to enter the war on April 6. The first troops arrived in June 1917, but the lion’s share didn’t get there until October of 1917. We know that Neill was back in California, directing LOVE LETTERS—his first film as a director—by November of 1917. Of course, it is possible that Neill served as a British pilot overseas during World War I, but his credit timeline in California makes this unlikely.

[5] Details regarding California Studios are hard to come by. Brent M. Christo, sales and marketing coordinator for Sunset Gower (as of 2012), will tell the LOS ANGELES TIMES that, “the history of Sunset Gower is a bit sketchy because the studio was once part of an area known in Hollywood lore as Poverty Row…‘There were a lot of little guys who started in this area. It was literally an office, a desk, a phone and a wastepaper basket. They sprung up overnight and folded just as fast.’” It’s 1918 when Harry and Jack Cohn—with Joe Brandt—form CBC Film Sales, which becomes Columbia in 1924.

[6] It’s unclear as to whether this was Carlos Edwin Corwin (credited as Carl Corwin) or Giovanni Ventimiglia, both of whom worked on the film. The eruption finally ends on June 29.

[7] This may be another fabrication. I can find no other source to verify it.

[8] Over the years, it has been alleged that actual, paying patrons in theaters watched the original cut of the film and laughed, forcing Universal to withdraw it and make changes. This is not actually the case.

[9] By the time he plays Dracula in ABBOTT AND COSTELLO MEET FRANKENSTEIN (1948), the studio has become Universal-International.

SOURCES

Brunas, Michael, John Brunas and Tom Weaver. UNIVERSAL HORRORS. Jefferson, NC: MacFarland & Co. Inc., 1990. Print.

Clayton, David. THE CURSE OF SHERLOCK HOLMES. Gloucestershire: The History Press, 2020. Print.

Crow, James Francis. “Kay Aldridge to Be ‘Hero’ of Western Pictures at Republic.” LOS ANGELES EVENING CITIZEN NEW. October 8, 1942, p. 4. Print.

“Eyes of the Underworld.” AFI CATALOG OF FEATURE FILMS. www.afi.com. Web.

Fleck, Bill. “A Chat with the Man Behind BORIS KARLOFF: THE MAN BEHIND THE MONSTER.” BILL FLECK’S CLASSIC HORROR BEHIND THE SCENES. www.billfleck.substack.com. Web.

“Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man.” AFI CATALOG OF FEATURE FILMS. www.afi.com. Web.

King, Susan. “Sunset Gower Studios, Former Home of Columbia, Marks 100 Years.” LOS ANGELES TIMES. October 15, 2012. Web.

Neill, Roy William. “Credits.” AFI CATALOG OF FEATURE FILMS. www.afi.com. Web.

“Noted Grad of St. Mary’s Dies.” THE OAKLAND POST ENQUIRER. December 16, 1946, p. 3. Print.

Riley, Philip J., ed. FRANKENSTEIN MEETS THE WOLF MAN: THE ORIGINAL SHOOTING SCRIPT. Absecon, NJ: MagicImage Filmbooks, 1990. Ebook.

Rosado, Luis. “On the Sets.” MONROVIA NEWS-POST. December 8, 1942, p. 4. Print.

“Roy William Neill.” THE NASHUA TELEGRAPH, December 16, 1946, p. 5. Print.

“Roy William Neill.” IMDb. www.imdb.com. Web.

“Sherlock Holmes and the Secret Weapon.” AFI CATALOG OF FEATURE FILMS. www.afi.com. Web.

“Sherlock Holmes in Washington.” AFI CATALOG OF FEATURE FILMS. www.afi.com. Web.

Siodmak, Curt. WOLF MAN’S MAKER. Lanham, MD: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2001. Print.

“Taylor-Neill Vows to Be Taken Today.” THE LOS ANGELES TIMES. July 19, 1942, p. 11. Print.

“Toilers of the Sea.” AFI CATALOG OF FEATURE FILMS. www.afi.com. Web.

Wright, Virginia. “Double Citizenship.” DAILY NEWS. July 20, 1943, pp. 21, 24. Print.

Wright, Virginia. “Entertainment.” DAILY NEWS. June 5, 1942, p. 31. Print.

Note: The pictures herein are used for educational purposes only. I do not own the copyrights.