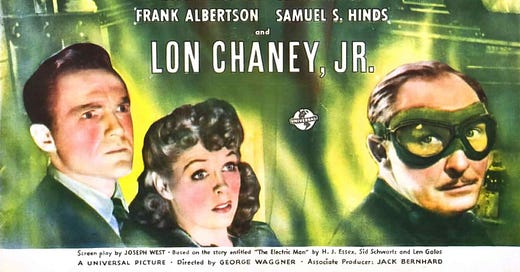

CLASSIC HORROR BEHIND THE SCENES: George Waggner And THE MYSTERIOUS DOCTOR R

Or, how George Waggner shaped an old Karloff-Lugosi script into the starring vehicle for Lon Chaney, Jr. that landed the actor a prized long-term contract with Universal.

By Bill Fleck, author of the Rondo-nominated book CHANEY’S BABY, available here.

Did you know? Two-time Rondo-Award winning filmmaker Thomas Hamilton is in the process of making VINCENT PRICE & THE ART OF LIVING. (I’m lucky enough to be a producer on the project.) Check out Tom’s project by clicking here. For information about possibly joining the Ignition Group and helping to get HORROR ICONS produced, click here. Thanks!

Check out other articles on this Rondo-nominated blog by clicking here.

What follows is adapted from CHANEY’S AUDITION: MAN MADE MONSTER AND THE THORNY ROAD TO THE WOLF MAN, my latest book…which I’m planning to release in the next several months. I hope you enjoy this preview!

August 1, 1935. Universal buys a story called “The Electric Man” from writers Harry J. Essex, Sidney Schwartz, and Len Golos.

“It’s based on a true story I read about,” Essex, who had been a reporter for THE NEW YORK DAILY MIRROR, will later explain. “A government organization was performing tests on electricity and the human body, how much we use up throughout the day and how we ‘recharge the battery’ by sleep at night…if there was some way to recharge the body’s electricity, we wouldn’t have to eat or sleep.”

Batting the idea around with fellow reporter Schwartz and press agent Golos at the MIRROR one day, Essex and Schwartz decide to get down to the actual writing—with Golos hitching what Essex describes as “a free ride.” Before long, the story is grabbed from their agency by Universal.

As Essex recalls, the studio—then under the control of Carl Laemmle, Jr. [1]—pays roughly $3300 for it, worth about $73,000 in today’s dollars.

[Above: Writer Harry J. Essex, the brain behind “The Electric Man.” Universal developed the story for Karloff and Lugosi, renaming the project THE MAN IN THE CAB.]

Junior Laemmle has the story turned into a screenplay called THE MAN IN THE CAB. He intends it to be another co-starring vehicle for actors Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi.

Karloff, penciled in as the Electric Man, apparently finds the idea to be amusing.

“I can shoot sparks in every direction, like the rays of the sun,” he’ll explain. Lugosi, meanwhile, is expected to play the evil scientist who comes up with all of this.

Lugosi and Karloff, meanwhile, begin shooting the somewhat similar THE INVISIBLE RAY (1936). [2]

But by March of 1936, Carl Laemmle Jr. is out as studio chief. He’s practically bankrupted the place by overspending on director James Whale’s SHOW BOAT (1936). By April, Junior is no longer welcome on the lot as a producer, either.

A deal is cobbled together and Universal is sold. J. Cheever Cowdin, a Wall Street loan specialist, snaps up the stock. Producer Charles Rogers lands the job as production chief. Rogers takes a quick look at THE MAN IN THE CAB and summarily dismisses it. The script goes into the dust bin to die.

In spite of the change in leadership, the company is still hemorrhaging money. Something needs to be done. Universal’s board of directors votes Nate Blumberg in as president, effective January 1, 1938. Blumberg—divisional manager of RKO theaters, among other things—blames Rogers for the financial havoc, and decides Rogers has to go. With Cowdin’s support, Blumberg begins to work the situation to that end.

By May 20, Blumberg has his cake and eats it, too. Rogers is out, and Cliff Work—who had once managed the Golden Gate Theater—is his replacement. Blumberg and Work are simpatico in that they believe in entertaining the public with product that doesn’t break the bank…often to the detriment of the contract players.

“Universal was an awful studio to work for,” Maxene Andrews of The Andrews Sisters will recall years later. “They never spent any money on our pictures. They expected you to work your tail off and we got nothing in return, not even a thank you.”

But the bruised egos of paid performers aren’t something that Blumberg and Work are concerned with. It’s the bottom line that counts.

And by 1939, the bottom line is swollen in part thanks to the very profitable SON OF FRANKENSTEIN. Which means horror films are in again. [3]

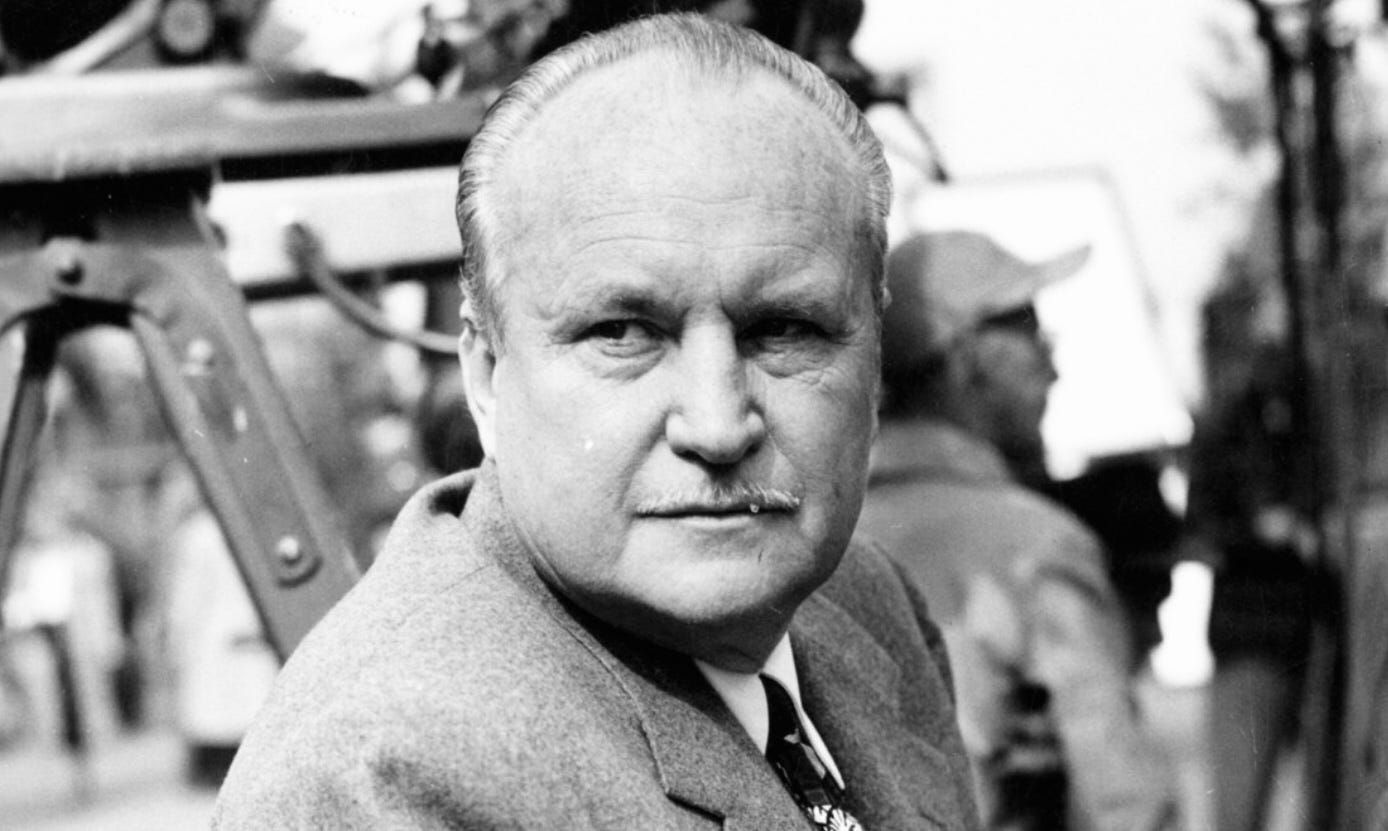

George Waggner is a man who understands this.

And Lon Chaney, Jr. will soon directly profit.

[Above: Writer-director-producer George Waggner. Universal charged him with the responsibility of dusting off THE MAN IN THE CAB and reshaping it for Lon Chaney, Jr., whom the studio was considering signing to a long-term contract.]

Of German ancestry, Waggner is born in New York City on September 7, 1894. He’s walked many roads before landing at Universal.

To begin with, he’s a graduate of the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy. His plan? To become a doctor. But the Great War puts the kibosh on that when the U.S. Army comes calling. From 1916 through 1920, Waggner serves as an officer.

When Waggner is discharged, he completely shifts gears by going into acting. He stumbles into THE SHIEK (1921)—which stars Rudolph Valentino—and plays Buffalo Bill Cody in THE IRON HORSE (1924). Columnist Harrison Carrol will later claim that Waggner “acted with the first Lon Chaney in TELL IT TO THE MARINES. He played a corporal, Chaney a sergeant.” However, no modern source verifies this.

Additionally, columnist Hubbard Keavy will later write that both Waggner and makeup artist Jack Pierce “often worked with Chaney, Sr.” during their acting days, though Keavy doesn’t cite any specific projects, and was likely just taking Waggner at his word.

What can be verified is that Waggner also gets into songwriting. He composes music for THE FLYING FOOL (1929). He’ll eventually write more than one hundred songs, including “Sweet Someone” (1927). Co-written with Baron Keyes, the tune becomes something of a standard, being recorded over the years by Billy Vaughn, Vic Damone, Tennessee Ernie Ford, and Don Ho (among others). [4]

Interestingly, three of Waggner’s songs—co-written with Edward Ward, who will write seven Oscar-nominated scores including Waggner’s PHANTOM OF THE OPERA (1943)—are featured in the Monogram comedy GIRL O’ MY DREAMS (1934). One of them, “Thou Art My Baby,” is sung—and well, in a ringing baritone—by none other than Creighton Chaney.

When acting and songwriting don’t cut it, Waggner tries his hand at screenwriting—sometimes under his own name (e.g., the story and screenplay for GIRL O’ MY DREAMS), and sometimes under his pseudonym, Joseph West—and also starts directing.

[Above: Mary Carlisle, Edward J. Nugent, Gigi Parrish, and Creighton Chaney in GIRL O’ MY DREAMS (1934). Not only did Waggner write the screenplay; he co-wrote several songs for the film as well…one of which was belted out by Chaney in an excellent, enthusiastic baritone voice. Waggner would later help Chaney land a long-term contract with Universal as Lon Chaney, Jr.]

“He was a commercial director, not like one of the gifted directors such as Huston, Wilder, King, LeRoy, who directed million-dollar blockbusters,” screenwriter Curt Siodmak—THE WOLF MAN (1941)—will write years later. “He had started as a writer, though there wasn’t any spark in his imagination. For him, I was the perfect complement to his craft, since he depended on a writer with original ideas.”

Married to Ruby Shannon with one daughter called Shy, Waggner has recently turned 46 when THE MAN IN THE CAB lands on his desk.

See what you can do with this, he’s told.

Waggner rewrites the script and changes the title to THE HUMAN ROBOT. He submits this version by November 15. Following a trip East—there’s talk that a musical based upon his 1925 song “Mary Lou” may be staged—he returns to Universal and begins to make revisions. Subsequent rewrites also feature title changes: THE MYSTERIOUS DOCTOR R (which will be the film’s working title), and then simply DOCTOR R.

A draft of DOCTOR R dated November 23, 1940—and presumably the shooting script, since Waggner is contracted to direct the film four days later—basically outlines the story as seen in the film.

But there are significant differences.

The action in the script begins with a truck driver trying to seduce a hitch-hiker he’s picked up. She’s not having it, and physically fights off his advances in the cab. The frustrated driver loses control and rolls the truck onto some railroad tracks…directly into the path of an on-coming electric train. A major crash results, during which a high-tension wire falls directly on the train.

It crackles with fatal current as sparks fly.

“CRASH FATAL TO TEN,” the headlines scream. “PASSENGERS DIE INSTANTLY—ONLY ONE SURVIVOR.”

The one survivor, of course, is Dan McCormick, described as “a giant of a man seated on the edge of the bed protesting to the nurse in attendance.”

As in the film, Dr. John Lawrence pays Dan a visit at the hospital, shows an interest in his story, and invites him over to his digs at 515 Forrest Drive, The Moors.

When Lawrence gets home, he’s greeted by his secretary, June Meredith—who, in the script, is not his niece as she is in the film. She is described as “about twenty-three, efficient yet attractive and between her and Dr. Lawrence is a warm regard.”

Lawrence then goes to the lab to check on his colleague, Dr. Ivan Rigas (Paul in the film). Interestingly, Rigas is described as “about thirty-five—an unusual man. [5] His head is large—almost too large for his body. His eyes are blazingly alive—perspiration stands out on his too white forehead from the effort of his concentration as he watches the effect of his experiment.”

Waggner’s intention to heighten the impact of Rigas’s menacing nature is evident in this aside: “(Note: This introduction of Dr. Rigas will be as photographically effective as is possible to make it.)”

As in the film, Lawrence and Rigas clash a bit over Rigas’s theories…which, of course, include the idea of creating a race of humans who are completely controlled by electricity. As in the film, Rigas declares that all of the geniuses in the world—Archimedes, Galileo, Newton, et al.—were thought to be mad, but have since been hailed as geniuses.

We’re then introduced to Mark Adams of The Globe Despatch [sic] as he waits with June the next day in an attempt to interview Dr. Lawrence.

“He is about twenty-eight,” Waggner writes, “a newspaper man—not ‘Scoop,’ the cub reporter. At no time does he say—‘Hold the presses—I got a story that’ll blow this town wide open—!’”

Lawrence, meanwhile, is in the lab with Dan, who’s playing with “Bullker, a mongrel dog.” [6]

Notably missing in the script is a warm exchange in the film, when Dr. Lawrence notices how quickly Dan has befriended the pooch.

“Hey you must be alright,” Lawrence says admiringly. “He doesn’t usually make friends very easily.”

“Sure, me and dogs always get along,” Dan explains with a smile. [7]

As in the film, Dan happily accepts Lawrence’s offer to work with him as a test subject, since—as he explains—the $18 bucks a week he’ll get as “compensation for the accident…don’t start for two weeks.” [8]

And then he’s introduced to Rigas.

[Above: Lionel Atwill as Paul Rigas in MAN MADE MONSTER. Called Ivan Rigas in the shooting script, it is obvious that Atwill helped Waggner shape the character on the set…much to the film’s benefit.]

In the film, a nicely-played scene between Ann Nagel (as June) and Chaney follows, while Dan horses around outside with the dog. But in the script, June is already in Lawrence’s library, half-heartedly resisting Mark’s efforts to date her.

With Dr. Lawrence away at a conference, it’s Rigas who is now in charge. The film closely follows the script here, except that Pete—a lab rabbit whose disappearance concerns Dan—isn’t mentioned. (Might Dan’s concern about a rabbit be an insider nod to the character of Lennie? Whatever the case may be, Rigas’s response in the film to Dan’s inquiry is classic Lionel Atwill…a humorous but menacingly dismissive, “Oh, he worked yesterday.”)

Of course, Rigas gradually turns Dan into an electricity-dependent automaton, described in the script on page 45 as “superhuman. His face is glowing; his eyes are deep in their sockets; his strength is prodigious…His makeup is fearsome; his strength is enormous.”

Rigas decks Dan out in the rubber suit, which—unlike the film—includes a helmet…an element that is wisely eliminated from the celluloid version.

Waggner’s proposed visual is designed to inspire awe.

“[Dan] in rubber suit and gloves,” he writes. “He is really a fearsome sight. His face glows brightly. He has gained in stature.” [9]

[Above: As depicted in the script, Dan McCormick becomes a fear-inspiring, soulless beast. This transfers effectively into the film…aided by Chaney’s presence and the fact that the script’s proposed helmet for McCormick has been eliminated.]

Of course, John Lawrence stumbles in during the pinnacle of Rigas’s triumph, and is killed for his trouble. As in the film, Rigas uses mind control to get Dan to take the blame.

In an effective scene that doesn’t appear in the film, Dan is questioned by the district attorney and an assistant at the D.A.’s office. Dan, guarded by two detectives, is unresponsive until the D.A. calls him on his attitude.

“It is also my duty to warn you,” the D.A. says, “that your sullenness and general lack of co-operation can’t help but influence this office in the prosecution of your trial…and while you admit that you killed Dr. Lawrence—”

“I did,” Dan interrupts. “I killed him—!”

And then, something inside of him wakes up…

“He rises as though tortured by all this questioning,” Waggner dictates on page 57. “The detectives grab hold of him and he faces the district attorney defiantly for a moment then relapses into his former condition.”

“Take him away,” the D.A. says.

From here, the film closely follows the script again: June and Mark suspect Dr. Rigas has some hand in Lawrence’s death, but they don’t have any proof; the district attorney’s office carries out a perfunctory investigation; Rigas is asked to be present at an examination which will determine Dan’s sanity.

This examination—which is a dramatic highlight in the film—is possibly even more intense in the script.

“Dr. Bruno, the chief alienist,” Waggner instructs, “is talking to Dan in what professional gentlemen believe is a soothing tone but which, to a layman, is the most irritating vocal effort imaginable since it is a blend of condescension, patronage and downright superiority.”

[Above: George Meader as Dr. Bruno, who—as described in the script—is “talking to Dan in what professional gentlemen believe is a soothing tone but which, to a layman, is the most irritating vocal effort imaginable since it is a blend of condescension, patronage and downright superiority.”]

Bruno recaps Dan’s childhood. The orphanage. The beatings. The desire to get even with his tormenter. How Dan sees Dr. Lawrence as that tormenter for hurting him with his experiments…

“You keep telling yourself you got even,” Bruno pushes. “You feel better, don’t you?”

“No—!” Dan replies hollowly. “I don’t feel better—I’m burning up inside…”

He glares at everyone in the room.

“What are you doing to me—?” he asks pathetically, sinking more deeply in his chair. [10]

Of course, Dan is convicted in court and sentenced to death in the electric chair. The way his attempted execution plays out in the script is wildly different from the film.

To begin with, we’re right inside the death chamber with Mark and other invited witnesses. Dan is brought in by two guards, accompanied by the warden and a priest.

“His trouser legs are slit,” Waggner notes on page 72. “His hair is shaved away on one side and he wears a loose sleeved shirt. He is oblivious to everything but the chair.”

While the priest “keeps up a constant drone of Latin prayer,” Dan is strapped in the chair and blindfolded. Electrodes are adjusted. The priest stands by with a crucifix.

And then, a close-up of a clock tells us it’s 11 PM.

The executioner closes the switch…

The horrific action unfolds in the manner described in chapter one [of the soon-to-be released CHANEY’S AUDITION]. Along the way, Waggner provides some vividly graphic images…images that, in hindsight, would likely never have been approved by the folks over at the Production Code Administration. Among these:

· “DAN (SHADOW) as the current hits him. He jerks violently and strains against the clamps that hold him.”

· “DAN (SHADOW) (NIGHT) as he is galvanized by the current. / INT. DEATH HOUSE – MED. CLOSE SHOT – MARK (NIGHT) in a group of spectators watching with growing horror.”

· “MED. CLOSE SHOT – DAN – (NIGHT) as the current hits him. A deep throaty cry is wrung from him.”

· “MED. CLOSE SHOT – DAN – (NIGHT) in chair, struggling. The cry is repeated. The despairing cry of a soul in torment. The electric hum continues—Dan’s struggles grow wilder.” [11]

· “MED. CLOSE SHOT – DAN – (NIGHT) as he tears loose from another clamp and stands menacingly. He tears the blindfold from his eyes with a chilling shout. He takes a step toward the spectators.”

[Above: In the script, the attempted execution of Dan—and his subsequent escape—is depicted in brutal detail, and, as such, was unlikely to pass muster with film censors. In the film, much of the action is handled off-screen…and is perhaps better off because of it.]

As in the film, Dan takes the warden hostage and makes his escape. [12] He steals rubber boots, accidentally sets a horse-drawn hay wagon on fire, and arrives at the Lawrence residence just in time to save June from being electrocuted by the depraved Rigas. (Interestingly, Atwill’s perverted, unhinged speech regarding females being “more sensitive to electrical impulse” than are males isn’t written here—more on this in CHANEY’S AUDITION.)

Rigas tries to dodge Dan by hiding in a closet, but no luck. Clutching the doorknob when Dan tries to enter, Rigas is fried, his “lifeless but rigid body” cashing to the floor.

With cops circling the house and in hot pursuit, Dan dons his rubber suit. And in spite of June’s protests—“There must be some way to cure you”—he scoops her up and carries her into the woods. The cops—and Bullker—desperately follow.

Sadly, Dan stumbles into a barbed wire fence. A “broken strand whips around his leg. There is a tearing SOUND followed by a flash…tearing [the] leg of [the] suit. He is stricken. He reaches June across the fence and drops her.”

Some of the detectives raise their guns, intending to shoot. The D.A. stops them.

It’s just a matter of time now.

“The electricity is snapping and crackling as it runs from him onto the wire,” Waggner writes. “He is in torment—shrinking within his rubber suit as the life-giving electricity leaves him.”

Bullker “howls mournfully.”

The loyal canine runs forward as Dan “falls from the wire, lifeless—a hulk within the rubber suit.”

“All that is left of Dan is the rubber suit and faint wisps of smoke [13],” Waggner directs. “Bullker, the dog, enters cautiously to whimper pitifully over the remains of his friend.” [13]

[Above: One of the saddest endings in the Universal Horror canon: Everyman Dan McCormick, destroyed by the experiments of the mad Dr. Rigas, dies a final death while Corky the Dog mourns his loss. Much of the good will Dan generates in the film is thanks to Chaney’s sensitive performance.]

The denouement as written is pretty much the same as in the film. Mark intends to print the records of Rigas’s mad experiment in his newspaper, but is talked out of the idea by June.

“Do you think you ought to make it possible for anyone else to do what was done to Dan?” she reasons.

Mark knows she’s right. He tosses Rigas’s notes into the fireplace, where the cracking flames consume them.

The End.

Wednesday, November 27, 1940. As noted above, Universal—obviously pleased with Waggner’s script—contracts him to direct the film as well.

“The picture will be cast right away and start Dec. 7,” columnist Edwin Schallert announces.

Interestingly, on November 28, Schallert notes that “Peter Lorre and Lionel Atwill are being pursued by Universal to take leading parts” in the film.

“They both have been identified with thrillers,” Schallert notes, “Lorre, naturally, more than Atwill. Already cast are Lon Chaney Jr., Frank Albertson and Anne Nagel.”

Waggner’s been given three weeks in December to shoot on a budget of $84,000. [14] It’s the cheapest film Universal will produce that year.

Oh, and Waggner will be expected to jump into HORROR ISLAND—his next project—immediately after. Universal intends to release it with THE MYSTERIOUS DOCTOR R as a double feature.

They’ve got the right guy. Waggner may not be a visionary like James Whale, but he knows how to inspire good performances…and how to shoot quality footage on time and within a budget.

Along the way, he makes some last-minute changes to the story and adds crucial scenes that will bolster the film’s emotional power.

To begin with—similar to what he’ll do later in THE WOLF MAN—he decides that June should be Dr. Lawrence’s niece. This family connection makes Lawrence’s murder that much more painful.

Then, too, Waggner develops additional scenes for Chaney that are designed to showcase his character’s decency and charm, traits that Dan and Lon Jr. actually share. These scenes contrast perfectly with the soulless, destructive hulk he becomes at Rigas’s hands, underscoring the tragic loss of a genuinely nice guy.

And finally, Waggner—no doubt with Atwill’s eventual help—finds interesting ways to suggest the inner depravity of Paul Rigas, the chief villain—a depravity that Atwill will convey with flair…perhaps because it is not entirely unknown to him in his private life.

[Above: Lon Chaney, Jr. in 1941. Before MAN MADE MONSTER was even released, he was signed to a long-term contract at Universal…which put him on the thorny road to screen immortality in THE WOLF MAN.]

NOTES

[1] Junior’s father, Carl Laemmle, Sr., founded what would eventually evolve into Universal Pictures in 1912 with seven other partners. Laemmle eventually bought out the others, and opened Universal City Studios in California in 1915. Irving Thalberg was in charge of production in the early 1920s. The films Thalberg oversaw included THE HUNCHBACK OF NOTRE DAME (1923) with Lon Chaney. In 1928, Laemmle put Junior in charge as a present for his twenty-first birthday.

[2] Weaver, Brunas, and Brunas suggest that the similarities between THE INVISIBLE RAY and THE MAN IN THE CAB might have been what sunk the latter. (See Weaver, et al., p. 244.)

[3] Legend has it that Karloff and Lugosi’s THE RAVEN (1935) is responsible for getting horror films banned in Britain. But Jim Ivers has provided an excellent analysis on this subject. According to Ivers, objections to horror films in Britain were overplayed by censor Joseph Breen because he—Breen—didn’t like them. A gullible press repeated Breen’s claim. Studio battles with the Production Code Administration over DRACULA’S DAUGHTER, THE WALKING DEAD, and THE DEVIL-DOLL in 1936 caused Hollywood to throw in the towel. (See “The Horror Film Hiatus of 1936-1938.”) When re-releases of DRACULA (1931) and FRANKENSTEIN (1931) prove to be very profitable, Universal reverses the no-horror-flick policy and puts SON OF FRANKENSTEIN into production. It, too, is a hit, paving the way for Lon Chaney, Jr., and MAN MADE MONSTER.

[4] Several of Waggner’s obituaries assert that “Sweet Someone” was also recorded by Bing Crosby, but I haven’t been able to verify this.

[5] Lionel Atwill, who will eventually play Rigas, is 55 as of the date of the screenplay.

[6] Part bull terrier, part cocker spaniel in the script. In the film, the dog will be a terrier mix called Corky. According to www.imdb.com, the dog was actually named Corky, and made at least 38 appearances in films and TV from 1933 through 1953…including three episodes as Laddie on THE DANNY THOMAS SHOW.

[7] A trait shared in real life by Chaney, who famously loves dogs. This is likely the reason why this exchange between Dr. Lawrence and Dan is added to the film.

[8] About $385 at this writing, just shy of $20,000 per year.

[9] In the film, Chaney wears shoes with lifts while suited in the rubber garb. These, of course, make the already tall actor even taller.

[10] Missing is the shot of Rigas staring Dan down and resuming the mind control.

[11] It would have been very interesting to see how Chaney would have handled this scene, given how effectively he could lose it onscreen (e.g., the climactic scene in 1943’s SON OF DRACULA).

[12] Interestingly, Waggner has a police radio announcer describe Dan as “six feet two inches—gray streak in his hair,” which matches Chaney’s publicized height. His actual height is tougher to pin down. Prone to exaggeration, Chaney often claimed 6’3”—and some publicity claimed 6.3.5”—but actor Mikey Knox, George to Chaney’s Lennie in a 1948 revival of OF MICE AND MEN, said no (as did Calvin Thomas Beck in 1975’s HEROES OF HE HORRORS, stating on p. 235, “In reality he was just six feet tall.”) Film historian Gregory William Mank in his book on the film version of OF MICE AND MEN (1939) writes, “actually he was about 6’” (Mank, p. 151). Looking at Chaney face-to-face with the taller Patric Knowles in FRANKENSTEIN MEETS THE WOLF MAN (1943)—and given that Knowles claimed to be 6’2”—I’d say Chaney was closer to 72-73” than 74-75.5”…

[13] Dan’s exit in the film is a bit more dignified, in that his body remains.

[14] According to Bernard F. Dick. Weaver, Brunas, and Brunas estimate the budget at about $86,000 (see Weaver, et al., p. 244).

SOURCES

“Albertson, Frank.” CREDITS. www.imdb.com. Web.

Brunas, Michael, John Brunas and Tom Weaver. UNIVERSAL HORRORS. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., Inc., 1990. Print.

Carroll, Harrison. “Behind the Scenes in Hollywood.” THE SACRAMENTO UNION. November 29, 1941, p. 9. Print.

“Cobina Wright Jr. in Long-Term Contract Deal at 20th Century.” LOS ANGELES EVENING CITIZEN NEWS. November 15, 1940, p. 8. Print.

Costello, Chris. “Celebrity Friends On and Off the Big Screen.” ABBOTT & COSTELLO NEWSLETTER, July 2023. Print.

Dick, Bernard F. CITY OF DREAMS. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1997. Print.

“Director, Songwriter George Waggner Dies.” SANTA CRUZ SENTINEL. December 12, 1984, p. 11. Print.

Fleck, Bill. CHANEY’S BABY. Wurtsboro, NY: Just Pay the Ransom Music, 2021. Print.

“George Waggner, 90; Known for Horror, Action Films.” THE LOS ANGELES TIMES. December 16, 1984, p. 93. Print.

Ivers, Jim. “The Horror Film Hiatus of 1936-1938.” April 27, 2014. www.spookyisles.com. Web.

Keavy, Hubbard. “In Hollywood.” THE SACRAMENTO UNION. November 23, 1941, p. 45. Print.

Mank, Gregory William. BELA LUGOSI AND BORIS KARLOFF. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2009. Print.

Mank, Gregory William. IT’S ALIVE. San Diego/New York: A.S. Barnes & Co., Inc, 1981. Print.

“Production Schedule.” EVENING VANGUARD. December 12, 1940, p. 8. Print.

Schallert, Edwin. “John Payne Awarded ‘Lucky Baldwin’ Lead.” THE LOS ANGELES TIMES. November 27, 1940, p. 15. Print.

Schallert, Edwin. “Lupe Velez, ‘Big Boy’ Teamed by Universal.” THE LOS ANGELES TIMES. November 28, 1940, p. 10 (Part II). Print.

Siodmak, Curt. WOLF MAN’S MAKER. Lanham, MD: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 1997, 2001. Print.

Svehla, Gary J. and Susan Svehla, eds. LON CHANEY, JR. Baltimore: Midnight Marquee Press, Inc., 1997. Print.

Waggner, George. DOCTOR R. (screenplay). November 23, 1940. Print.

“Waggner, Ruby Danny.” THE LOS ANGELES TIMES. June 25, 1977, p. 55. Print.

Wass, Janne. “Man Made Monster.” September 20, 2019. www.scifist.net. Web. Accessed February 17, 2024.

NOTE: The pictures utilized herein are intended for educational purposes only, under the concept of fair use; I do not own the copyrights.