Classic Horror Behind the Scenes: Lon Chaney’s Biggest Mistake

The multi-talented Silent Era film star was a happy, down-to-earth, private, and honorable man of his word. But in telling his only child that the boy’s mother was dead, he made a huge mistake.

By Bill Fleck (adapted from the Rondo-nominated book CHANEY’S BABY, available here.)

Lon Chaney would hate this article.

He was fiercely private, and wisely counseled friends and family to behave in the same way. Talking publicly about his exceptional work was one thing; letting the public dance to reports of private matters was another.

Entirely.

“Between pictures,” he was known to say, “there is no Lon Chaney.”

It was his thinly-disguised message to the press: buzz off.

In many ways, I agree with him. So, I should stop writing here, right?

Well…maybe not.

Lon Chaney was a major star. He made his mark at Universal, then signed with MGM—a very major studio—in 1924. He lived a life that was virtually scandal free. Offscreen, he avoided the Hollywood scene; rather, he socialized with family and film technicians, was not above taking a drink, smoked too many cigarettes, and enjoyed both hunting and fishing. His humor and genuine charm were integral parts of his personality.

[Above: Offscreen, Lon avoided the Hollywood scene. He preferred hanging with family and film technicians. Plus, he loved the outdoors.]

The one big scandal in his life—his divorce from Cleva Creighton, his first wife and the mother of his son—wasn’t really his fault. Certainly, any intimate relationship is complex, and at times, couples in trouble don’t behave at their best. Still, at least at first, Lon Chaney tried to behave honorably.

But then anger and fear caused him to lie to the one person who needed to trust him the most: his sensitive son, Creighton.

“Kid,” he could have said, “your mother and me had a bad divorce. Sometime down the road, maybe I can tell you more. Let’s just say that, right now, I don’t think you’d be safe with her. When you get older, you can look her up and see if things are different.”

But he didn’t. He wanted Cleva Creighton out of his life—and their son’s.

Totally.

Irrevocably.

So, for reasons he believed were correct, he told the boy that his mom was actually dead. And both of them lived their lives as if it were true.

But when his lie was exposed after his death, [1] it caused excruciating emotional pain, explosive anger, and long-lasting grief he couldn’t possibly have intended.

With divorce and blended families so prevalent in our culture, perhaps a lesson can be learned from this incredibly destructive incident in the otherwise admirable Lon Chaney’s life…even if he would have hated talking about it.

April 30, 1913. Cleva Creighton Chaney watches her husband from the wings of the 1600-seat Majestic Theatre in Los Angeles. He’s frolicking on stage dressed as a clown.

As he acknowledges the applause and exits the stage, Cleva catches his eye.

Then, she swallows a vial of bichloride of mercury and crumbles at his feet.

Cleva is 23. Of Irish ancestry, she’s tall and thin with dark hair, blue eyes, and a beautiful singing voice. She’s a popular cabaret singer who is expected to drink with clients after the show, which she does—to her husband’s ever-increasing exasperation.

They have a 7-year-old son named Creighton.

[Above: Cleva Creighton was a beautiful and talented singer who captured Lon Chaney’s heart in 1905.]

Cleva is born Frances Cleveland Creighton on August 20, 1889 in Kansas. Her father John is a drunk who ditches his wife and four kids. Her mother Martha—commonly known as Mattie—supports the family by working as a practical nurse, a cook, and a washerwoman.

By the time she’s 15, Cleva is working the switchboard at the phone company in Oklahoma City. It’s there that a girlfriend shows her an ad in the local paper:

The Columbia Musical Comedy Repertoire Company is looking for chorus girls.

“You ought to try out for that, Cleva,” the girlfriend says. “Gee, with a voice like yours! Look what you might do—get to be an actress.”

Mattie, however, is dead set against the idea.

“You stay away from there,” she tells her daughter. “I don’t hold with girls going on the stage. It’s not your class. You’ve got a good job. Stay where you are.”

The next day, however, Cleva manages to convince her mother to at least let her audition.

At the theater, a young man emerges from behind the scenery. He’s wearing a sweater and overalls. A cigarette burns in his mouth. He looks Cleva up and down.

“Nope,” he says.

He’s Lon Chaney. Among the many jobs he does for the company is recruiting local talent. It makes sense—you can’t travel the theater circuit profitably hauling a large group of dancers around, but local folks are bound to spend a few bucks to see their relatives on stage.

Chaney is a dancer himself—a good one. Born Leonidas Frank Chaney in Colorado Springs on April Fool’s Day in 1883, he’s just shy of 22. But he’s seen a few things.

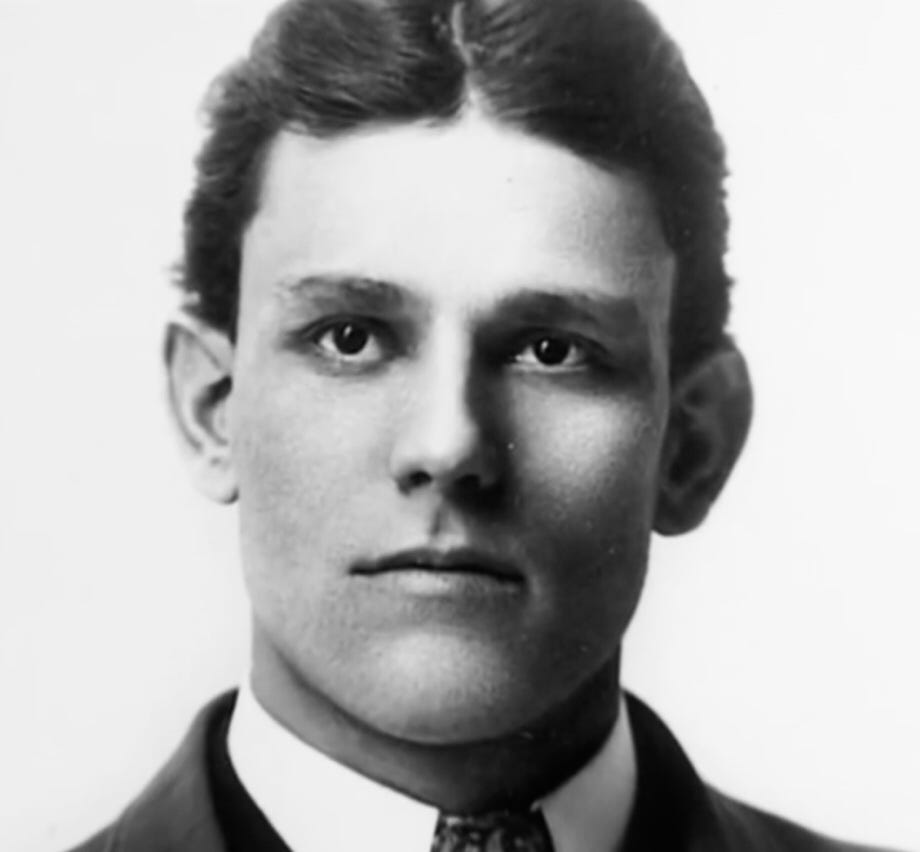

[Above: Leonidas Frank “Lon” Chaney, c. 1905. Ruggedly handsome, supremely talented, and a man of his word.]

To begin with, both his parents are deaf-mute. Frank Chaney and Emma Kennedy met at a school for the mute—established by Emma’s father—and married late in 1877. Frank made his living as a barber. Lon has an older brother named Jonathan, a younger sister named Caroline, and a baby brother named George. Their parents raised them on a gospel of hard work and self-reliance. Weakness was shunned.

Illness confines Emma to bed early in Lon’s life. He foregoes school to help care for her and develops a penchant for pantomime—a skill that will eventually make him his fortune. His older brother manages a theater, and it’s there that Lon gets his start in 1902.

Now he’s in Oklahoma City looking Cleva over. And he instinctively knows she can’t dance. He turns to go back to work.

“Maybe you’d like to hear me sing?” Cleva tries.

“Sure,” he smiles, “but I’m awful busy this morning.”

“I can sing,” Cleva insists.

It’s obvious that she isn’t going away.

“Shoot,” Chaney says with a laugh, giving in.

She launches into a number, a cappella. Yeah, she can sing. And how!

“You’re hired,” he says.

Cleva is thrilled. Not only does she have a job in the theater, but she’s also smitten with her new boss.

Lon Chaney in 1905 is ruggedly attractive. He’s five-seven and 150 pounds, with dark hair parted in the middle and a strong jaw. Most impressive are his expressive brown eyes, set under thick brows. Plus, he has a quick sense of humor and a boatload of talent.

Over the next few days, he tries to teach Cleva to dance, but this proves to be impossible. Instead, he finds ways to utilize her magnificent voice on stage.

And he falls in love with her.

As a result of his puritanical upbringing, many of the characteristics Chaney decidedly manifests in full adulthood have already taken root in him. His code of ethics. His attention to detail. His desire for privacy. His strict ideas about loyalty. His love of the outdoors, the company of close friends, and the sharing of a few drinks.

Romantic love is something new to him.

Lon Chaney is not a trusting person. But he trusts Cleva Creighton and gives her his heart. She reciprocates.

They have a whirlwind summer.

But late in the fall, Cleva has something she needs to tell him. She’s pregnant.

Neither Cleva nor Lon is ready for this. Both are just starting their careers—how are they ever going to manage with a kid?

Panic overtakes them. Things get tense. Cleva will say in later years that Lon even suggests that she should get an abortion.

Instead, they decide they need stability. They claim to be married. In December, they return to Oklahoma City so Cleva’s mother can help out.

Needless to say, Mattie is in full “I-told-you-so” mode when she hears the news. In her mind, Chaney’s behavior has reinforced everything she believes about theatrical folks being immoral.

For his part, Chaney gets a job in a furniture store owned by a family named Tull. He’s paid $15 a week—about $425 when adjusted for inflation at this writing. Borderline poverty money…plus, he’s not following his passion.

Though Lon’s initial displeasure regarding the pregnancy has worried her—Cleva knows he has the memory of an elephant, and fears he may one day resent her—she’s grateful to find that he’s very sweet and supportive during the months before she delivers. And she needs that care and support because her pregnancy is a rough one. Her discomfort is constant, and she spends nearly all of her time in bed.

Saturday, February 10, 1906. Cleva prematurely delivers a son. Initially, the baby suffers from lack of oxygen, but rallies. [2] They name him Creighton Tull Chaney—Creighton after his mom, and Tull after Lon’s kindly boss at the furniture store.

Thursday, May 31, 1906. Lon and Cleva quietly—but finally officially—take out a license to marry. In later years, they will try to cover up their unwed status at the time of Creighton’s birth. [3]

[Above: A poor-quality reproduction of a photo of the Chaney family. Cleva, with her looks and singing voice, was initially the more successful, and was expected to drink after shows with male clientele. This—understandably—became an issue between she and her husband.]

With renewed enthusiasm, the Chaneys decide that life on the road working in the theater has to be superior to raising their son in Oklahoma City, especially since Mattie isn’t warming up to Lon.

But once on the circuit, money is a constant issue. Bookings evaporate if ticket sales lag. The Chaneys stash every cent they can as a bulwark against unemployment. Lon will be obsessive about money for the rest of his life.

Things between them begin to fall apart when Cleva initially proves to be the more popular performer. This, of course, is not hard to understand. Cleva is attractive and a great singer. When business is slow for the comedy troupe, she’s able to pick up gigs in cabarets. She puts on a show for sure, and is expected to drink with the clientele—mostly male—afterward, which she’s happy to do.

Slowly, the teetotaling girl who took Lon Chaney’s heart in 1905 is developing a drinking problem.

Then, too, jealousy enters the picture. Chaney—working like a maniac, trying to set his career on fire—is not the most attentive of husbands.

Cleva craves attention. She often finds solace talking with bartenders. When Chaney realizes that his wife is treating other men as confidants, he goes ballistic. Is she cheating on him?

“Don’t be too hard on Cleva,” Lon’s brother John advises.

But the jealousy cuts both ways—Cleva is angered herself when she perceives that pretty showgirls are flirting with her man.

By 1912, Cleva is billing herself as Cleva Creighton rather than Cleva Chaney.

What’s she trying to tell him?

Cleva and Lon aren’t alone in their pain. Their son Creighton is affected, too. Yes, he is clothed and fed, but his folks are often too busy to spend time with him, and he’s pawned off on company players—Hazel Hastings and Fay Parkes in particular. As of 1912, Creighton has yet to attend school.

Sadly, when Lon does spend time with his son it’s often because Cleva is too drunk to take care of him herself.

“I guess I was just a woman who shouldn’t ever have taken a drink,” Cleva will admit years later.

Things reach a breaking point when Chaney—doubling as stage manager at The Majestic—plans to hit the road with the Kolb and Dill Company when they leave California. Cleva is not happy about the idea. She and Lon clash—hard.

Cleva becomes frantic. After her show at the Brink’s Café, she heads to the Majestic Theatre and tries to persuade her husband one last time.

But Lon is unmoved.

And so, Cleva stands in the wings, catches Lon’s eye, and downs the poison.

She’s rushed to the hospital in an ambulance. Lon—beside himself, and still dressed as a clown—rides with her.

Bichloride of mercury is bad stuff. Not only is mercury deadly; the substance is corrosive. Surviving a dose like Cleva has taken is unlikely.

But at the hospital, police surgeons treat her with antidotes. When she regains consciousness, they ask her what happened.

“I quarreled with my husband,” Cleva says, “and life had lost its brightness.”

She begs throughout the night to see her son.

Thursday, May 1, 1913. Cleva’s doctor takes Lon aside.

“She’ll live,” he says, “but she’ll be a sick girl for a long time.”

Lon is both relieved and concerned. But he’s honorable and intends to make an effort to fix his marriage.

“It’s true we quarreled,” he tells The Los Angeles Herald, “but my wife had no intention of attempting suicide. She believed she was swallowing medicine. Our differences are all straightened out now.”

Of course, this isn’t true—Cleva was very much trying to kill herself, as she admits to The Los Angeles Daily Times that very same day. The private Chaney needs people to think he’s telling the truth.

Intending to put the pieces of his family back together, Lon allows Creighton to spend some time with his mom after her release from the hospital while they work things out.

But by May 26, the Chaneys are separated—Chaney has come across some information that cuts him to the core: a yet-to-be mailed letter Cleva has written to Don A. Traeger, one of her bartender friends:

“My dearest boy: Received your letters and will take a few lines before I go to breakfast. Creighton is in the bathtub and I am in my nightgown. I sent you a letter about three days ago and gave it to a girl to mail. Did you get it? I told you that I was working at Clunes, 5th and Main. Gee, honey, you don’t know how sick I am of work. I don’t know what is the matter with me. The doctor says I have lost control of my nerves. I am taking medicine all the time. Say dearie I hope you can come here within two weeks as it will be much easier for me to see you while I am at Clunes. Well Don I must close and wash the baby. Yours all the time with love, Cleva.”

Lon Chaney is nothing if not loyal.

But it’s obvious that his wife is not.

Lon confronts her, understandably attempting to get to the bottom of things. Cleva admits to being in love with Traeger. She’s also expecting money from him. She says she’s done with Lon. For Chaney—whose motto might as well be, “When I’m through I’m through, and when I’m through, I’m all through”—this is proof-positive that Cleva needs to be cut out of his life.

He will never trust her again—in any capacity.

Attempting to build a slam-dunk divorce case, Chaney begins spying on his estranged wife. In addition to being involved with Traeger, he determines that she has been “shacking up” with Charles Osmand, another bartender.

Is this how the mother of an innocent child behaves?

In Lon Chaney’s mind, the answer is no. And he is going to make her pay.

But he’s going to unintentionally wound his son deeply in the process.

December 13, 1913. Lon Chaney files for divorce from Cleva Creighton. He petitions for sole custody of his son.

Not only will Cleva no longer be his wife.

She will not be Creighton’s mother, either.

But how will he explain her absence to the child?

Wednesday, April 1, 1914. Lon turns 31.

He’s also in court attempting to divorce Cleva.

His charges are devastating. Adultery. Habitual intemperance. The infliction of mental anguish on her husband.

Cleva is a no-show. A letter to her estranged husband is entered for the court’s consideration:

“Don’t think I am going to ask for forgiveness. I want permission to see our boy. I have paid and am still paying dearly for it. But you don’t care and I can’t expect even a word from you; but for God’s sake grant my only hold to the name of Chaney, and let me see my dear baby. I would be a slave or anything else just to see him. I promise I will not beg your forgiveness or harm you in any way. I know, Lon, that you loved me once, and to think I am not worthy of that love. Lon, I am almost crazy. Please return good for evil once more as you have always done with me.”

Even in the depths of her despair, Cleva recognizes that Lon had tried to be good to her.

The next day, the judge returns his decision. The bans of marriage will be dissolved in one year’s time, and Chaney will have “care, custody and control” of Creighton.

There is a proviso: “[B]ut that defendant be permitted to see said child at all reasonable times, provided that defendant not be under the influence of liquor, and that she conduct herself in a proper manner.”

There is no chance in Hell that Lon Chaney is going to allow this in any way, shape, or form. He firmly believes that Cleva’s behavior would endanger their child.

“What could I do?” Cleva will say in 1950. “I didn’t have a penny. I didn’t know where Lon and the boy were. The stuff I’d taken did something to my vocal cords. When I tried to get a job, I opened my mouth and couldn’t sing a note. Lon didn’t know about that.”

In other words, Cleva basically gave up on attempting to reach her child. This will be a major issue between mother and son when they finally reconnect in later years.

In the meantime, Chaney isn’t exactly living large, either.

To begin with, the scandal surrounding Cleva’s suicide and their divorce costs him his job with Kolb and Dill.

Then, on April 8, a heart attack kills his mother.

Finally, he’s hustling so much that his sister Carrie has to take care of 8-year-old Creighton.

Something has to give.

In what turns out to be a fortuitous decision, Chaney decides to give motion pictures a try. He puts Creighton in a home for children of divorce and disaster while attempting to make some money. He visits the boy on Sundays.

Up until now, Lon has handled an explosive situation in the best way possible to preserve his dignity and secure safety for his little guy.

But then, he makes his huge mistake.

He tells Creighton that Cleva is dead.

In so doing, what exactly is Lon Chaney thinking? Sure, she’s dead to him, so this may be a beneficial—though selfish—fantasy. Moreover, Lon is genuinely concerned that Cleva, in her current capacity, is an unfit parent; cutting her off at this point might make sense.

But insisting she’s dead is devastating for Creighton. The vulnerable boy feels abandoned by his mother’s ‘death.’ A distrust of women begins to grow in him.

And how will Lon ever explain this to Creighton if-and-when the kid finds out he’s been lied to about something so crucial?

Lon Chaney has weaved a tangled web.

[Above: Creighton Chaney and his father. Lon loved his son, but feared for him—he saw too much of Cleva’s personality in him. In a misguided attempt to protect Creighton, Lon lied to him, telling the boy that his mother was dead. This lie would have major repercussions after Lon’s death in 1930…repercussions Lon never intended.]

Friday, November 26, 1915. The courthouse in Santa Ana, California. Lon Chaney and Hazel Hastings get hitched.

Born Marie Genevieve Hazel Bennett in San Francisco, the 28-year-old Hazel is a former dancer. Catholic, and Italian on her mother’s side, she’s tiny—standing only 4’10”—but very smart.

[Above: Lon and his beloved wife Hazel. They made a great team, and Hazel always encouraged Lon to demand to be paid what he was worth.]

The match is a good one. Like Chaney, Hazel is a veteran of a bad first marriage—hers was to Charles Stuart Hastings, who sells cigars and is supposedly severely handicapped. She and Chaney also share an ability to immediately—and accurately—size up people and situations. As the years go on, they will very much be partners in both business and life.

Oh, and Chaney will tell everyone that Hazel is Creighton’s mother.

[Above: Creighton, 16, and Hazel see Lon off at the train station. Lon would tell everyone that Hazel was Creighton’s mother.]

By the time they get 9-year-old Creighton out of boarding school and bring him home—1607 Edgemont Avenue, Los Angeles—Chaney is making $45 a week over at Universal, worth a little less than $1300 at this writing when adjusted for inflation. As time goes on, this is raised to $60, then to $75.

But the always shrewd Hazel thinks her husband is being cheated. She knows what his talent is worth.

“You will ask for $150 a week from now on,” she tells him. “There are not many in the movies with your stage experience…A man must never settle for less than he is worth.”

Chaney balks, at first. But he eventually makes the demand…and gets it.

[Above: Lon’s breakthrough film was THE MIRACLE MAN (1919). His gift for elaborate makeups set him apart from other actors, and contributed to making him a star.]

Still, no matter how rich and famous Chaney gets—and he gets very rich and famous—two things remain constant:

There will be no mention of Cleva. Ever.

And Creighton will not be coddled.

“He’s no rich man’s son,” Chaney says. “He’ll earn what he gets, the same as I did.”

[Above: Today, Lon is remembered for roles in thrillers like THE HUNCHBACK OF NOTRE DAME (1923) and THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA (1925). But his roles were in no way limited to the horror genre.]

True to his word, Chaney is not raising Creighton like a rich man’s son.

Beginning at age 14, Creighton is expected to have a job after school and every summer. He works in slaughter houses and butcher shops. He picks apricots. He also tries out for Hollywood High’s football team, but is cut—though he’s already six feet tall, he’s a string bean at 125 pounds.

At one point—after appearing in small parts in school plays—he asks his father about maybe making a few bucks as an extra in films, something some of the other kids do on the weekends.

Lon Chaney will not hear of it.

Chaney thinks Creighton should be a bank teller or maybe a plumber. Every time the possibility of an acting career for his son is mentioned, Chaney washes it away in freezing cold water.

“He’s 6’2” tall,” Chaney says as late as 1928. “That’s too tall. He’d have to have parts built around him.” [4]

Underneath it all, however, something more sinister lurks—something Chaney sees whenever he catches his son’s sad, hazel eyes.

He sees Cleva.

Like Cleva, Creighton is overly sensitive. He requires attention. He has self-esteem issues. Criticism cuts him deeply.

In today’s world, we’d say that both Creighton and his mother are bipolar.

Growing up in the wings of the theater, being passed around to various relatives and friends, and residing in foster homes and boarding schools before finally entering a stable phase at the age of nine has crippled Creighton emotionally. Who can he believe in? And how does he know?

Chaney understands how hard it is to make it in The Biz. He doesn’t trust his own success, and he describes himself as “hard-boiled.” How would the inevitable career knocks affect his son, who is soft like his mother? Creighton won’t even stand up to bullies in school—how will he ever be able to handle Hollywood?

Might he—like Cleva—maybe even contemplate suicide?

“I just don’t want my son in this business,” he’ll confide in a friend. “Maybe he’d survive. Most of them don’t. It’s a crazy racket. You know that. I’d been through hell and back before I got into it, so it didn’t upset me much. Besides, I could afford to stay away from most of it. The kid’s different. I want to keep him out of Hollywood. I’m not afraid he’d be a failure. I’m afraid he’d be a success. I’d rather he’d be a good plumber than a movie star.”

In short, Chaney believes failure would damage his son.

And success would kill him.

Sadly, Lon Chaney thinks he’s giving Creighton the lessons he needs to overcome his growing demons. But deep down, Lon’s tough-love approach confuses his son. Like Cleva before him, Creighton finds Lon’s aloofness—in the attempt to make a man out of him—disturbing. Plus, he senses his father’s reservations about him. The idea that Pop thinks he isn’t tough devastates him, causing him to worry about his masculinity.

And then John Jeske enters the mix.

Born in Skierniewice, Poland on May 7, 1890 to a Polish mother and a German father, the 30-year-old Jeske has been in the United States since 1912. Initially, he works at his brother’s bakery in Scranton, PA, but by 1914, he’s living in Los Angeles. He works as an auto mechanic and applies for U.S. citizenship in 1920.

By 1923, he’s just started duties at Louis Mansey’s garage near Hollywood when Lon Chaney—a regular customer, and a friend of Mansey’s—pulls in.

Who’s the new guy? Chaney asks the owner. Mansey introduces them.

Chaney and Jeske—who resembles Chaney enough to be mistaken for his brother—hit it off. Before long, Jeske is officially hired as the Chaney family’s chauffeur.

Unofficially, Jeske quietly helps Lon with his makeup and costumes—"unofficially” because all the publicity says that Lon Chaney does everything himself. Jeske’s first assignment? THE HUNCHBACK OF NOTRE DAME (1923).

Behind closed doors—following Chaney’s instructions, of course—Jeske helps work up and apply the materials necessary to turn Lon into Quasimodo.

[Above: Lon and his friend John Jeske from the front cover of Suzanne Gargiulo’s excellent book, LON CHANEY’S SHADOW. Jeske was loyal to both Lon and Hazel, but his presence in their lives made Creighton jealous.]

Before long, Jeske becomes a staple at the Chaney home as well. This does not sit right with Creighton.

Now a junior in high school, Creighton—who has an inherent dislike of people he perceives to be “foreigners”—is suspicious of Jeske because he’s German. (This is odd, given his father’s broadminded view on such matters.) [5]

When Jeske begins spending more and more time with his beloved Pop, Creighton’s aversion becomes definite dislike.

Why isn’t Dad spending his time with me?

[Above: Lon in TELL IT TO THE MARINES (1926) and in THE UNHOLY THREE (1930), his only Talkie. Had he lived, he would have undoubtedly made an impression in pictures for years to come.]

August 28, 1930. Lon Chaney, 47, is dead…a victim of lung cancer.

Characteristically, he had kept his illness as secret as is possible.

Outside the Los Angeles funeral parlor, a large crowd has gathered spontaneously. Police are called to control them.

Inside, Hazel Chaney is screaming, “Why? Why? Why?”

Creighton attempts to comfort his stepmom, but he’s at a loss as to how. It doesn’t help that Jeske is one of Pop’s pall bearers. A nurse takes charge of Hazel.

“Laugh, Clown, Laugh”—Chaney’s favorite song from one of his favorite films—floats up from behind the flowers and fills the chapel.

September 4, 1930. Lon Chaney’s estate is probated.

Chaney has left behind $550,000, worth about $10.2 million as of this writing. Hazel, as his “dear, beloved wife,” receives most of it, plus $150,000 in real estate and $125,000 in personal property.

Oddly, Cleva Creighton benefits as well: “So that there may be no misunderstanding or contest of any kind whatsoever,” Chaney instructs, “I hereby give and bequeath to Cleva Creighton Bush the sum of $1 and no more. I am divorced from Cleva Creighton Bush and I am under no obligations whatever to provide anything further or additional than herein contained.”

Even in death, Lon Chaney has a long memory.

As for Lon’s siblings—and his son—the will instructs that $275,000 in life insurance is to be split four ways. Each share would be worth about $1.3 million today.

Still, what gets under Creighton’s skin is the fact that John Jeske—“at all times loyal to me,” Pop has decreed—is awarded $5000 for himself, worth about $93,000 today.

With the Great Depression on, Creighton—now married with two sons—thinks that money should be his. Did Pop value Jeske more than he valued his own son?

His smoldering rage is ignited again when it becomes obvious that Jeske and Hazel are leaning on each other for support after Pop’s death. Whose side is Hazel on?

But what really sets him off is that his mother is still alive.

When Creighton finds out that Pop and Hazel had lied to him about Cleva’s death, he is understandably apoplectic. The implications are devastating.

What gave them the right to steal his mother from him?

How can he ever trust Hazel again?

Or the memory of his father?

In a boiling rage, Creighton goes on a tear. He behaves miserably at home. He threatens Hazel’s attorneys with lawsuits. He confronts Hazel—now dying of breast cancer—and Jeske. Both begin to fear him, and soon hatch a crackpot plan to marry in order to protect Chaney’s assets (a plan which is scotched only when it’s leaked to the papers).

“I always got the impression that the boy never quite forgave his father when after Lon was dead, young Creighton—known professionally as Lon, Jr.—found out about his own mother and went to see her,” Adela Rogers St. John, “The World’s Greatest Girl Reporter,” will write. “It also seemed to me he held it against his stepmother, who was always very kind to him, that Lon Chaney had left her outright every penny of his fortune to do with as she pleased.”

St. John’s impression is dead on.

Inevitably, of course, Creighton decides to go and see Cleva. Things between them are awkward at first. Still smarting from his father and stepmother’s deception, he also harbors a resentment toward Cleva for abandoning him. He simply can’t understand why his mom wouldn’t have moved mountains to be a part of his life, no matter what his father’s wishes may have been. She might not have actually been dead, but in not fighting Lon harder in order to see her child, she might just as well have been.

Of course, Creighton’s default position is to blame himself. Is there something wrong with him? Is he that unlovable? His distrust of women becomes worse.

Eventually—though he’ll never mention her in interviews—Cleva and Creighton forge a relationship.

[Above: Creighton—now known as Lon Jr.—with Cleva and his second wife Patsy in the 1950s. Though they eventually forged a relationship, he rarely—if ever—mentioned Cleva in public.]

But Creighton Chaney’s feelings for his father have changed. Before long, he’ll happily defy Pop’s strictest edict by indulging in what Greg Mank calls his “almost vengeful dream.” [6]

He’ll become an actor.

And he intends to top the bastard.

As everyone who cares knows, Creighton Chaney had a dream: to make it in pictures on his own merits, and to top his father as an actor. Of course, he wasn’t able to achieve either.

It was, as Mank notes, a vengeful dream…payback for his father’s misguided lie.

True, as Lon Chaney Jr., he was wildly successful in his own right. He wasn’t a major star like Clark Gable or Humphrey Bogart—much less his father—but at the peak of his Universal days, he was making $3500 a week, worth about $2.5 million per year today. It’s not nearly what top-grossing performers got then or now, but that kind of money is certainly more than most of the rest of us will ever see.

Plus, he created at least two immortal screen characterizations: Lennie Small in OF MICE AND MEN (1939) and Larry Talbot in THE WOLF MAN (1941).

Even after Universal dropped him, Chaney did reasonably well as a freelancer, financially if not always artistically. Sure, he felt like he had to work constantly, but his standard of living remained good. He never needed to tap into the canned goods he hoarded.

But he never touched his father, who was universally revered and respected in his day…and among those in the know even now.

Creighton Chaney wanted to be his father’s son. But he was very much his mother’s baby. Her genetics are stamped all over him: tall, good looking, talented. So are her personality traits: a sensitive nature, insecurity, depression. And unfortunately, so are her behaviors: extramarital affairs, a destructive taste for booze, an attempted suicide.

Lon Chaney grew to hate Cleva Creighton. (By her own admission, he had reason to.) And by extension, Lon hated the parts of her that he could see in their son. This made Lon fear for his son. Lon tried to tough-love those traits out of him. His intentions were good, but he hurt Creighton deeply in the process, making the boy doubt himself.

Was Lon Chaney an abusive parent? Certainly not by the standards of his day, nor do I believe by the standards of today. [7] Sure, Creighton was passed around from friends to relatives and didn’t have a stable home until he was nine. But that’s the story of a lot of folks, even now. Later, Creighton had ample food and creature comforts, and his father certainly taught him a work ethic.

Where Lon Chaney made his biggest error was in telling Creighton The Lie that his mother was dead. It was unforgivable then, and it is unforgivable now. That Creighton found out only after Lon’s death is tragic—he was never able to confront his father, and all of his previously good memories of Pop were tainted.

As such, Creighton put Lon’s beloved wife Hazel through hell. She was really the only mother he’d ever known, and she’d been good to him, but it didn’t matter. She was in on The Lie. Creighton’s fight to obtain money from his father’s estate from her was rooted, I believe, in resentment—a resentment he didn’t want but couldn’t shake…because he couldn’t face what he thought it said about his father’s feelings for him. It’s telling that he was banned form Hazel’s hospital room before she died.

The effect of The Lie and this resentment rippled throughout his life, which ended in agony at the age of 67. [8]

Lon Chaney couldn’t have imagined this. Nor would he have wanted his precious family at each other’s throats. That some of it played out in the papers would have been anathema to him. Had he lived to see any of this, he would have been mortified. I believe he would have taken whatever steps were necessary to put a stop to all of it.

And I believe he would have kicked himself—but good!—for ever telling his boy that his mother was dead.

But he couldn’t, as he was dead by then himself. Had he lived, I think he’d have apologized, taken The Lie back a thousand times, and tried to repair things with his son.

If only he could have.

Yeah, Lon Chaney would have hated this article. But I think he would have appreciated the lesson.

Notes

[1] There are reports that Creighton learned the truth earlier—about 1925—and the Chaney bio film MAN OF A THOUSAND FACES (1957) portrays the situation in this way. But Chaney biographers Michael F. Blake and Suzanne Gargiulo have confirmed that Creighton learned the truth only after his father was gone.

[2] In later years, Creighton will say that he was born dead, and that his father had to break the ice on a body of water in the freezing cold and dunk him in to shock him into life. Stella Bush, Cleva’s daughter—and Creighton’s half-sister—denied this. Weather reports from the day make it unlikely as well; the Saturday Creighton was born was cloudy with rain likely; the day after was described as “fair” (“Weather Forecast,” The Daily Oklahoman, Feb. 10, 1906, p. 7. Print.)

[3] Cleva and Lon sometimes claimed to have been married in 1905; at other times, they said 1906, and pushed Creighton’s birth back to 1907. Suzanne Gargiulo has done the definitive research on this.

[4] Creighton’s publicity later will say he was 6’2”. Creighton himself will often claim 6’3”. But the truth is—as Greg Mank writes—“actually he was about 6’” (Mank, OF MICE AND MEN: MENTAL ENFEEBLEMENT, RACISM, AND MERCY KILLING IN 1939 HOLLYWOOD, p. 151).

[5] For example, Chaney had befriended the biracial actor Noble Johnson in school, and later helped him get started in films. Johnson is best known today for roles in THE MUMMY (1932), THE MOST DANGEROUS GAME (1932), and KING KONG (1933).

[6] Mank, OF MICE AND MEN…p. 167.

[7] Creighton’s alleged revelations to WOLF MAN screenwriter Curt Siodmak about the beatings he endured at the hands of his father aren’t taken seriously by Chaney’s family or biographer Michael F. Blake.

[8] “Friends said his last weeks were spent in ‘agony’ stemming from a series of recent illnesses.” (“Another Film Star Is Dead.” The Sedalia Democrat. Sedalia, Missouri. July 15, 1973, p. 13. Print.) However, Chaney Jr.’s widow, Patsy, told interviewer Gary Dorst that on the day of his death, he’d been feeling better.

Sources

Blake, Michael F. A Thousand Faces. Lanham/New York/Oxford: Vestal Press, 1995. Ebook.

Fleck, Bill. CHANEY’S BABY. Wurtsboro, NY: Just Pay the Ransom Music, 2021. Print.

Gargiulo, Suzanne. Lon Chaney’s Shadow. Orlando, FL: BearManor Media, 2009. Ebook.

Gourley, Jack and Gary Dorst. “A Man, A Myth, and Many Monsters.” Filmfax. May 1990. Print.

Mank, Gregory William. OF MICE AND MEN: MENTAL ENFEEBLEMENT, RACISM, AND MERCY KILLING IN 1939 HOLLYWOOD. Orlando, FL: BearManor Media, 2023. Print.

The pictures herein are for educational purposes only. I do not own the copyrights.

WoW! Thanks for a great article.