Classic Horror Behind the Scenes: “What Color Were the Wolf Man’s Clothes?” And Other Bits of Trivia

Monster Kids wanna know!

By Bill Fleck, author of the Rondo-nominated book CHANEY’S BABY, available here.

Okay, I admit it. I spend too much time scrolling through social media when I should be writing.

Most of the pages I hit on are dedicated to Classic Monsters. (I know—you’re shocked.)

But, come on…I grew up in an era where we were starved for information…information that could only be unearthed by buying expensive books.

Or, of course, subscribing to magazines like FAMOUS MONSTERS. (By the way, check out sometime who 4e dedicated issue #157 to…)

But now, some of the best stills I’ve never seen—and some of the most interesting commentary—turn up in microseconds at the touch of my finger, thanks to places like A SANCTUM FOR CLASSIC HORROR.

Or CLASSIC UNIVERSAL MONSTERS AND LUGOSI, CHANEY JR, KARLOFF.

Or LON CHANEY’S THOUSAND FACES.

Or UNIVERSAL MONSTERS & MONSTROUS MONSTER MISCELLANY.

(Please don’t be offended if I didn’t mention your page. These are the first four that came up on my feed, and I’m late writing my column this month. If I’m liking your stuff, I’m loving your page.)

Of course, there are more than just pictures and commentary. There are also questions. Legitimate, Monster-Kids wanna know questions.

These are a few that I’ve noticed more than once, and will attempt to answer as best as I can.

1. What color were the Wolf Man’s clothes?

Ah, yes…that famous buttoned up shirt and belted pants that the Wolf Man seems to have chosen to put on AFTER transforming for the first time. [1]

Universal seems to have made the answer easy for us. Their current licensed Wolf Man collector’s items and action figures feature a dark green shirt and brown pants. Case closed, right?

Well…

I’m old enough to be in possession of licensed collector’s items and action figures from years past…which feature a blue costume.

Or black.

Or a combination of black and blue. [2]

And let’s not forget that Universal once officially licensed Frankenstein monster products that featured a green jacket! How off was that?

So, where does that leave us?

[Above: Most—but not all—of the lobby cards for THE WOLF MAN in 1941 depicted his shirt and trousers as being blue.]

Naturally, a quick search on the internet yields a variety of opinions.

For example, the famous collector Bob Burns is said to be of the opinion that the Wolf Man’s clothes were brown…which they were when he photographed Chaney during the making of TV’s ROUTE 66 episode, “Lizard’s Egg and Owlet’s Wing.”

[Above: Noted collector Bob Burns snapped this color shot on the set of “Lizard’s Leg and Owlet’s Wing,” a 1962 episode on TV’s ROUTE 66. Chaney’s costume was clearly brown here.]

Then, on the Tapatalk forum, one commentator suggests Chaney wore green to honor American troops.

Well, Lon Jr. was a patriotic guy…

Others think the shirt, at least, was maroon or red, thanks to the famous portrait by Basil Gogos that adorned the cover of FAMOUS MONSTERS #99. The most popular “red-shirter” guess regarding the pants is gray.

And we have the fact that the vast majority of colorized lobby cards from the 1941 film—but not all—feature the Wolf Man in blue (my preference in my younger days).

Still, I can find only one authoritative print source, at least regarding his clothes in THE WOLF MAN (1941). To wit:

“[Jack] Pierce, working from a life-mask of Chaney’s face, fashioned a long wolf-like rubber nose and a thick wig…Pierce also created the wolf-like hands and feet, and costumed Chaney in a BLACK SHIRT AND TROUSERS [emphasis mine] so that the ordeal of body make-up would be avoided.” [3]

That unambiguous statement comes from HEROES OF THE HORRORS by Calvin Thomas Beck, one of those expensive—though excellent—books that I’ve alluded to above.

Given that there is seemingly only one authentic color picture of Chaney in the Wolf Man make-up—with Pierce, on the set of HOUSE OF DRACULA (1945)—and given that his shirt in that picture is black, it would seem that the mystery is solved.

[Above: The only known authentic color shot of Chaney in Wolf Man make-up (with Jack Pierce on the set of HOUSE OF DRACULA). His shirt here is clearly black. Does that mean the same for THE WOLF MAN (1941)?]

Until you look at publicity stills from 1941. Or compare his clothes to, say, Claude Rains’ in the film.

Are Larry’s pants and shirt dark? Clearly.

But do they look black? Well…not really. Certainly not the shiny, jet-black Chaney sports in the last scenes of ABBOTT AND COSTELLO MEET FRANKENSTEIN (1948).

Unless they’re that kind of dusky iron gray that some people consider to be a shade of black.

So now, we’re in the Land of the Educated Guess.

And I’m guessing that Beck got his information from a solid source who saw iron gray as black.

Feel free to disagree.

Oh, while we’re on the subject of THE WOLF MAN (1941):

2. Why is Bela a four-legged werewolf, but Larry is a wolf man?

Realistically, I’m betting that Universal suits didn’t want to bother with spending the time or the money to have Bela Lugosi made up. [4]

And it works better as a build-up to the Wolf Man’s first appearance anyway. Why tip your classic make-up hand so early in the film? [5]

And let’s face it…the makers of THE WOLF MAN had no idea that crazy folks like us would be obsessing over these things 80-plus years later.

However, if you’re looking for an in-context, thematic reason as to why Bela and Larry transform into obviously different creatures, you’ll do no better than the words of R.H.W. Dillard.

Dillard, known to friends as Richard, was a poet and a professor of creative writing at Hollins University in Virginia. College President Mary Dana Hinton described Dillard as being “synonymous with our English and creative writing program” upon his death in April 2023, aged 85.

Along the way, Dillard wrote more than ten books, including a collection of poems called THE DAY I STOPPED DREAMING ABOUT BARBARA STEELE (1966).

He also co-wrote the screenplay for FRANKENSTEIN MEETS THE SPACE MONSTER (1965) with George Garrett—later Poet Laureate of Virginia—and John Rodenbeck.

But for our purposes here, his most important work is HORROR FILMS.

Published in 1976, HORROR FILMS is one book I passed on back in the days of my 13-year-old ignorance. But I picked up a used copy later, and, boy, am I glad I did.

In a short but fully-packed 114 pages, Dillard applies his laser-beam analytic skills to four films: FRANKENSTEIN (1931), THE WOLF MAN (1941), NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD (1968), and Fellini’s SATYRICON (1969).

Do I have to tell you that, in 1976, a serious analysis of THE WOLF MAN was hard to come by?

[Above: Bela in werewolf form is a four-legged beast. Why did Chaney transform into a hybrid? Critic R.H.W. Dillard has the best thematic answer in his 1976 book, HORROR FILMS.]

Dillard’s chapter in HORROR FILMS is must-reading for any serious Wolf Man fans, but I’ll do my best to hit the salient points here:

To begin with, Dillard asserts that the central theme in the film is Larry Talbot’s “struggle between the present and the past, the free active life and the restrained bookish one.”

As such, Larry’s escape to the United States from his European home represents his desire to shake off the staid expectations of a stifling, predictable, aristocratic existence and to create his own identity as an individual, in control of his own destiny. In America, he reinvents himself as a physical man and leaves the pondering over the mysteries of the universe to intellectuals like his father.

But his older brother’s unexpected death brings him home, where the simple but moral man he’s become will clash with the entitled, above-the-law ‘Master Larry’ he’s expected to be.

In Dillard’s view, Larry’s story is also a retelling of the Fall of Adam—Larry’s even snitched apples as a kid—and the start of his undoing here comes as a result of his sexual desire for the engaged Gwen Conliffe. His flirting with Gwen upon their initial meeting leaves no doubt about his desires, revealing Larry’s internal, well, “wolf.” [6] (The fact that their chaperoned date is almost adulterous, almost a sin—“I really shouldn’t be here,” Gwen admits—will add to Larry’s dilemma.)

[Above: In Dillard’s view, director George Waggner’s concentration on Larry’s feet underscores his and Gwen’s sin of “walking out” while she was engaged to another man, which almost constitutes adultery.]

In killing Bela, whom he sees as a wolf—as do we—Larry executes what he believes to be a moral act of self-defense, as well as a justifiable but ultimately failed attempt to save Jenny, the chaperone they’ve ditched, from the jaws of death. But when he’s informed that he’s actually murdered a man—and when he sees that his doctor, his father, and his childhood friend (who is now the Chief Constable) are basically engaged in covering up for him—he begins to doubt himself.

For Larry, “freedom” under these conditions isn’t freedom at all.

Of course, Bela’s bite passes the lycanthropic curse onto Larry, who does all he can to deny it. But his American ideas regarding individuality and self-reliance are drowned by a sea of Old World teachings, which emphasize that there is no escaping your fate.

“Even a man who is pure at heart, and says his prayers by night…”

So, now again to the question. Larry, two legs…Bela, four.

Why?

“Bela, Maleva’s son, is thoroughly a part of that [old] world,” Dillard explains. “He is a palm reader…He feels regret when he sees the pentagram, the mark of the werewolf’s victim in Jennie’s [sic] hand, and warns her away, but he knows that both his regret and the warning are futile. When he becomes a wolf, he takes on the wolf’s form completely” (Dillard, pp. 41-42).

In other words, Bela has accepted his fate.

As for Larry?

“Talbot, who does not accept the understanding of the society he is in, struggles against the results of that way of seeing and believing…” Dillard goes on. “And when he does give in to his own darker impulses as shaped by that society, he does not change completely. He does not become a wolf; he becomes a wolf man, the actual concrete form of the moral tension within him” (Dillard, p. 42).

In other words, though Larry knows he is being punished for his lust (i.e., for being a ‘wolf’), he has NOT accepted his fate.

Hey, that’s the best answer to that question I’ve ever heard.

[Above: Significantly for Dillard, the Wolf Man is trapped by his foot. Dillard asserts that Larry becomes a wolf man because he has not accepted his fate.]

3. “How tall was King Kong?”

Fifty feet tall, right?

That’s what I was told, and that’s what publicity materials for the original film trumpet back in 1933.

But, of course, he isn’t.

Oh, he was close…at times.

But for the vast majority of the film, Kong is depicted as being eighteen feet high.

That’s because creator Merian C. Cooper thinks that an oversized monster would be a force of nature rather than a character capable of interacting effectively with humans.

Kong should be gigantic, Coop directs, but never so big as to cut off his interest in people.

As such, chief technician Willis H. O’Brien and his crew work on a one-inch-equals-one-foot scale, and Kong’s builder (Marcel Delgado) whips up at least two 18-inch versions of the beast.

[Above: Marcel Delgado’s Kong models were 18 inches tall. The one-inch equals one-foot scale the animators used in Skull Island scenes give Kong a height of 18 feet.]

But at times, Coop will order that Kong’s proportions be inflated for dramatic effect…much to the precise O’Brien’s chagrin.

That’s why when Kong smashes the wall and invades the native village on Skull Island, he appears to be much bigger than eighteen feet. He’s actually depicted here as being around forty.

[Above: Kong crashes into the native village. In scenes like this, Cooper wanted Kong’s proportions to be inflated. He appears to be almost 40 feet tall in this scene.]

Still, when Kong is taken to New York City, the first scenes are shot utilizing the one-inch, one-foot scale.

Until Coop sees the rushes.

“It isn’t big enough!” Coop complains.

“[Co-director/producer] Ernest Schoedsack agreed,” asserts the writers of THE MAKING OF KING KONG. “[H]owever awesome the gorilla had appeared within his own jungle, he was dwarfed by the towering stone cliffs and the incandescent brilliance of the big town.”

But what’s to be done?

No one concerned can stomach the idea of reshooting the jungle scenes in a new scale. Even if they could, there’s no way RKO will pony up the money.

So, they make the only decision they can.

They decide to shoot the NYC scenes in a different scale, making Kong twenty-four feet high.

And they hope no one will notice.

[Above: For the scenes in New York City, Cooper ordered that Kong’s standard height be increased to 24 feet.]

“We realized we’d never get much drama out of a fly crawling up the tallest building in the world,” Schoedsack will say years later.

And, of course, he was right.

4. And the last, for now: “Did Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff really hate each other?”

“Karloff? Sidekick?”

An old, decrepit—but proud—Bela Lugosi stares down a young lackey who has just asked about his sometime co-star on the set of GLEN OR GLENDA (1953).

“F--- you!” the actor suddenly explodes. “Karloff does not deserve to smell my s---! That limey c---sucker can rot in Hell for all I care!”

Director Ed Wood rushes over, obviously concerned.

“What happened?”

“How dare that a—hole bring up Karloff?” an enraged Lugosi replies.

It’s one of the most famous scenes in Tim Burton’s ED WOOD (1994) as performed by actor Martin Landau, who’ll score a Best Supporting Actor Oscar in part because of it.

It’s also complete fiction.

Did Karloff and Lugosi hate each other?

The short answer is no.

But they weren’t exactly friends, either.

More like professional rivals, or so at least Bela thought.

And—through no doing of his own—Karloff had the upper hand.

[Above: Lugosi and Karloff met and posed for publicity photos in early 1932. They certainly did not hate each other, but were never really friends.]

The situation dates back to when Lugosi—flush with stardom after DRACULA (1931)—turns down the role of the Frankenstein monster (or has it taken away…a more in-depth examination can be found in my blog here).

Of course, Karloff gets the part…and becomes a bigger star than Lugosi.

Though they meet for publicity photos shortly after—and though they are both active in getting the screen actor’s union off the ground—they never socialize off the set.

As far as Karloff is concerned, there’s nothing strange about this.

“I worked with Bela Lugosi in, oh, three or four pictures [7],” Karloff will explain years later, “but outside of the studio, we didn’t meet. You know [Hollywood’s] an enormous, rambling big place spread out all over southern California. You perhaps do a picture with somebody, and your paths don’t cross again for a year. It depends what your individual tastes were…I used to play a lot of Cricket, for years—which I don’t think would have appealed a lot to Bela” [8] (Jacobs, p. 154).

It's an honest assessment. Bela enjoyed reading, smoking cigars, walking his dogs, and throwing small parties for his Hungarian friends. Cricket didn’t enter into it.

Which is fine, because on his end, Bela seems to have had no issue with Karloff…at least, personally.

Professionally? Well, that’s a slightly different matter.

[Above: Though they posed for publicity shots and were friendly on set, Karloff and Lugosi never socialized away from the studio.]

While it’s true that the stars were always friendly on the set, for Bela, they were rivals when it came to being cast. It irked Bela that Boris was generally granted bigger parts…and was always better paid.

He was also bothered by the fact that Karloff got roles in other genres, while he was typecast as purely a horror guy.

But these were issues caused by Hollywood executives, not Boris himself. Bela most certainly was aware of that.

But it still hurt.

This poor treatment by the suits who controlled the purse strings is clearly illustrated by how Universal attempted to treat Lugosi during the making of SON OF FRANKENSTEIN (1939), which featured both Karloff and Basil Rathbone.

Though under a new regime, Universal’s Laemmle-era distaste for Bela remained. In fact, executives initially plan on taking advantage of him. They hire him as Ygor at $500 per week…then instruct director Rowland V. Lee to shoot all of Lugosi’s scenes in less than seven days!

This way, they can get his name on the marquee and lure in his fans on the cheap.

Lugosi knows that Universal would never pull a stunt like this on Karloff.

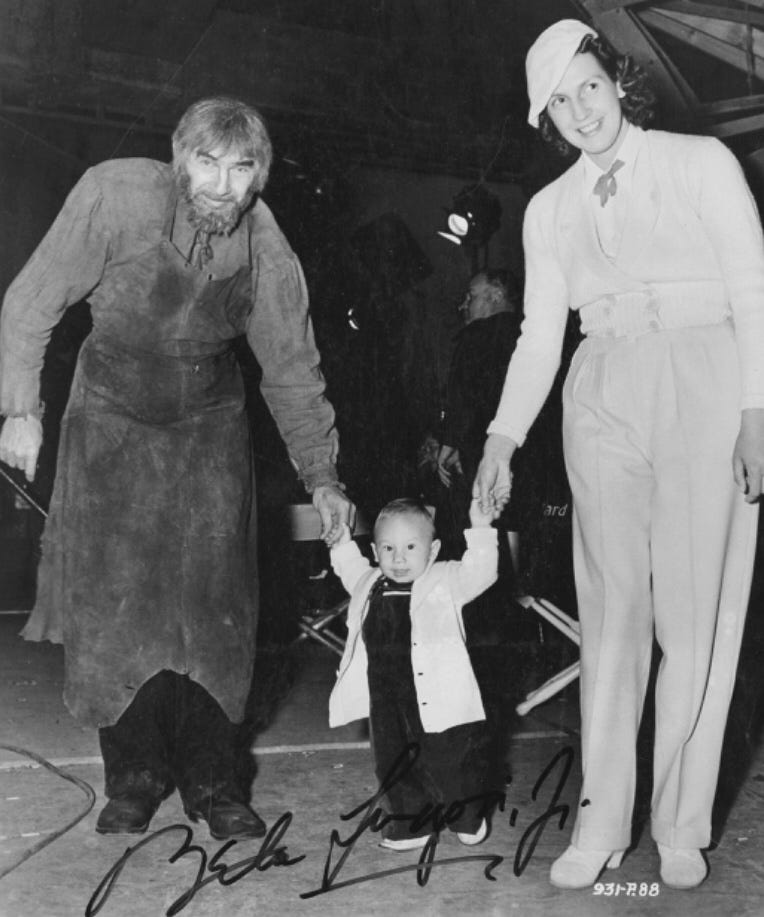

[Above: Bela as Ygor is visited on set of SON OF FRANKENSTEIN (1939) by son Bela George—who later signed the photo—and wife Lillian. The occasion? To give Karloff a gift in honor of the birth of his daughter, Sara. Bela always thought of Karloff as a professional rival of his own creation; Karloff thought Bela’s career was affected by Bela’s limited mastery of the English language.]

But Universal hasn’t factored in how stubborn their new star director can be.

According to Lillian Lugosi—Bela’s fourth wife, and mother of their son Bela George—Lee was outraged at Uni’s plan.

“I’m going to show those goddamn SOBs that they can’t do that to Bela,” the director told her. “I’ll keep him on the set from the very first day of shooting to the last minute. I’ll be damned if he doesn’t make as much as Karloff from the film” (Lennig, p. 263).

As a result, Lugosi turned in one of his best performances…in spite of the fact that—as Greg Mank puts it—he had “to see his rival each day in the very guise that helped Karloff snatch away Lugosi’s horror crown” (Mank, pp. 81-82).

Sadly, as excellent as he was, Bela’s performance in SON didn’t win him any champions in the front office. For the most part, the actor went back to lesser pictures and touring in stage revivals of DRACULA and ARSENIC AND OLD LACE.

But he never gave less than one-hundred percent.

In retrospect, Boris Karloff believed that Lugosi’s casting troubles were due to Bela not having learned English sufficiently.

“Poor old Bela…” he once mused after Lugosi’s death. “It was a strange thing. He was really a shy, sensitive, talented man who had a fine career on the classical stage in Europe. But he made one fatal mistake. He never took the trouble to learn our language. Consequently, he was very suspicious on the set, suspicious of tricks, fearful of what he regarded as scene stealing. Later, when he realized I didn’t go in for such nonsense, we became friends” (Jacobs, p. 154).

Bela, of course, was unable to respond to that. But he did mention making what amounted to a “fatal mistake” himself.

According to Bela, producer Carl Laemmle would only allow him to bow out of FRANKENSTEIN if he—Lugosi—could find another actor for the part.

“I scouted the agencies,” Bela would say later, “and came upon Boris Karloff. I recommended him…And that is how he happened to become a famous star of horror pictures. My rival in fact.”

Though that isn’t entirely the case, the gist of his comment is sound. [9]

“He made the greatest mistake of his career…” Lillian said in later years. “Bela created his own monster.” [10]

Got a Monster Kid question? I’m likely to do another blog like this in the future. So, send me what you’d like to know and I’ll see what I can do:

billfleckenterprises@gmail.com

NOTES

1. In a famously head-scratching turn of events, Larry Talbot tuns into the Wolf Man in his room at Talbot Castle, clad in light gray trousers and a white “wife-beater” T-shirt. Once he hits the woods, however, he’s dressed…well, differently. The concrete fact on film is that he must have changed his clothes, however unlikely that may be. In reality, it was a lapse in continuity. Similar lapses will occur in subsequent Wolf Man films.

2. See Sideshow Toys’ twelve-inch Wolf Man from 2001—light bluish-gray shirt, and dark brown-black pants. Or Sideshow’s eight-inch figure—dark greenish-blue shirt, dark blue-black pants. Or Sidehow’s eighteen-inch polystone statue—iron gray shirt, nearly black pants.

3. Beck, p. 241. Maddeningly, Beck provides no sources for anything in his book. The closest thing I can find to back him up is a syndicated column by Charles R. Moore, entitled “Hollywood Film Shop,” published on December 4, 1941 in The Clinton Daily Journal and Public. “The werewolf wears shirt and trousers,” Moore writes among other things, “so Chaney is spared having the rest of his body made up” (p. 2). Notice the color of the shirt and trousers is not mentioned.

4. Interestingly, though Bela in werewolf form is played mostly by Moose—Chaney’s soon-to-be favorite pet German Shepherd—there are also brief long shots of a man costumed entirely in black fighting Chaney. Was director George Waggner subliminally suggesting that while Talbot saw a wolf, he was actually killing a man? Or were certain shots just easier to grab with a stuntman rather than with Moose? I’m betting the latter…though the former is more interesting.

5. Of course, the werewolf’s face could have been obscured. But it’s difficult to argue the scene would have been improved. It’s excellent as is.

6. Dillard also asserts that Waggner’s focus on Larry’s feet—both in human and wolf form—underscores Larry’s “sin” of “walking out” with an engaged woman. I think it’s interesting to note that Larry’s aggressive flirting would be considered objectionable today. It’s also interesting that both Larry and Gwen are punished for walking out—Larry by being cursed and then killed, and Gwen by presumably having to spend the rest of her life with Frank Andrews, a man she obviously doesn’t love.

7. It was actually eight.

8. Karloff was a member of the Hollywood Cricket Club, along with C. Aubrey Smith, Basil Rathbone, Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., and David Niven among others.

9. Lugosi’s story is partly true; by not playing the Monster, he handed Karloff a golden opportunity. But it isn’t true that he got Karloff the part—that was James Whale’s doing.

10. Lillian also claimed that Lugosi’s experience working on SON OF FRANKENSTEIN (1939) was dampened by his co-stars Karloff and Basil Rathbone. “Basil Rathbone was verrrry British,” she said. “He was a cold fish, and Karloff was a cold fish. Bela, who was actually very warm, couldn’t tolerate either one of them!” (See Mank, Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff, p. 352.) But how did she know this? She is known to have visited the set—did she see this behavior for herself? Or did Bela come home with complaints? Personally, I feel that Lillian had more issues with the idea of Karloff than did Bela.

SOURCES

Beck, Calvin Thomas. HEROES OF THE HORRORS. New York: Collier Books, 1975. Print.

Bose, Swapnil Dhruv. “Exploring the Feud Between Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi.” Faroutmagazine.co.uk. February 2, 2022. Web.

Bullmore, Joe. “No Rest for the Wicket: Hollywood Cricket Club.” www.therake.com. January 2017. Web.

Dillard, R.H.W. HORROR FILMS. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1976. Print.

“Hollins Mourns the Loss of Celebrated Professor, Author, and Scholar R.H.W. Dillard.” Hollins.edu. April 7, 2023. Web.

Jacobs, Stephen. BORIS KARLOFF: MORE THAN A MONSTER. Sheffield: Tomahawk Press, 2011. Print.

Lennig, Arthur. THE IMMORTAL COUNT. University of Kentucky Press, 2003. Print.

Mank, Gregory William. BELA LUGOSI AND BORIS KARLOFF. Jefferson, NC: MacFarland and Co., Inc., 2009. Print.

Mank, Gregory William. IT’S ALIVE! San Diego: A.S. Barnes & Company Inc., 1981. Print.

Moore, Charles R. “Hollywood Film Shop.” Clinton Daily Journal and Public. December 4, 1941, p. 2. Print.

Turner, George and Orville Goldner and Michael H. Price. THE MAKING OF KING KONG. Pulp Hero Press, 2018. Ebook.

The images utilized herein are intended for educational purposes only. I do not own the copyrights.