CLASSIC HORROR BEHIND THE SCENES: "MAN OF A THOUSAND FACES" REVISITED

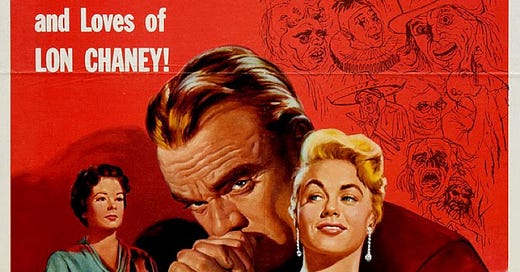

James Cagney stars as Lon Chaney in the famous biography. But how truthful is the now 68-year-old film?

By Bill Fleck, author of the Rondo-nominated book CHANEY’S BABY, available here, and the recently released CHANEY’S AUDITION, available here.

Did you know? Two-time Rondo-Award winning filmmaker Thomas Hamilton is in the process of making VINCENT PRICE & THE ART OF LIVING. (I’m lucky enough to be a producer on the project.) Check out Tom’s latest HORROR ICONS update here. For information about possibly joining the Ignition Group and helping to get HORROR ICONS produced, click here. Thanks!

Check out other articles on this Rondo-nominated blog by clicking here.

NOTE: It is assumed that the reader has seen MAN OF A THOUSAND FACES.

“I wonder how much damage to our collective understanding of how Chaney, Jr. grew up was caused by that fictionalization that happened in that movie?”

The question comes from Livo Merino, Chaney scholar and co-host—with Jim Towns—of the BORGO PASS HORROR podcast.

Livio, Jim and I were talking about MAN OF A THOUSAND FACES (1957), the famous Lon Chaney bio pic starring James Cagney.

And it’s a great question. How much influence does that film still have on our understanding—or, rather, misunderstanding—of Lon Chaney, his son, and his ex-wife?

(If you’re interested in hearing our discussion, it happens about 34 minutes into Borgo Pass’s “Bill Fleck, Author of CHANEY’S AUDITION” podcast, available on Apple here, or wherever else you catch your podcasts.)

Candidly, I hadn’t seen MAN OF A THOUSAND FACES in years. But it’s obvious that a lot of what folks think they know about Chaney comes from this film.

And a lot of it just isn’t accurate.

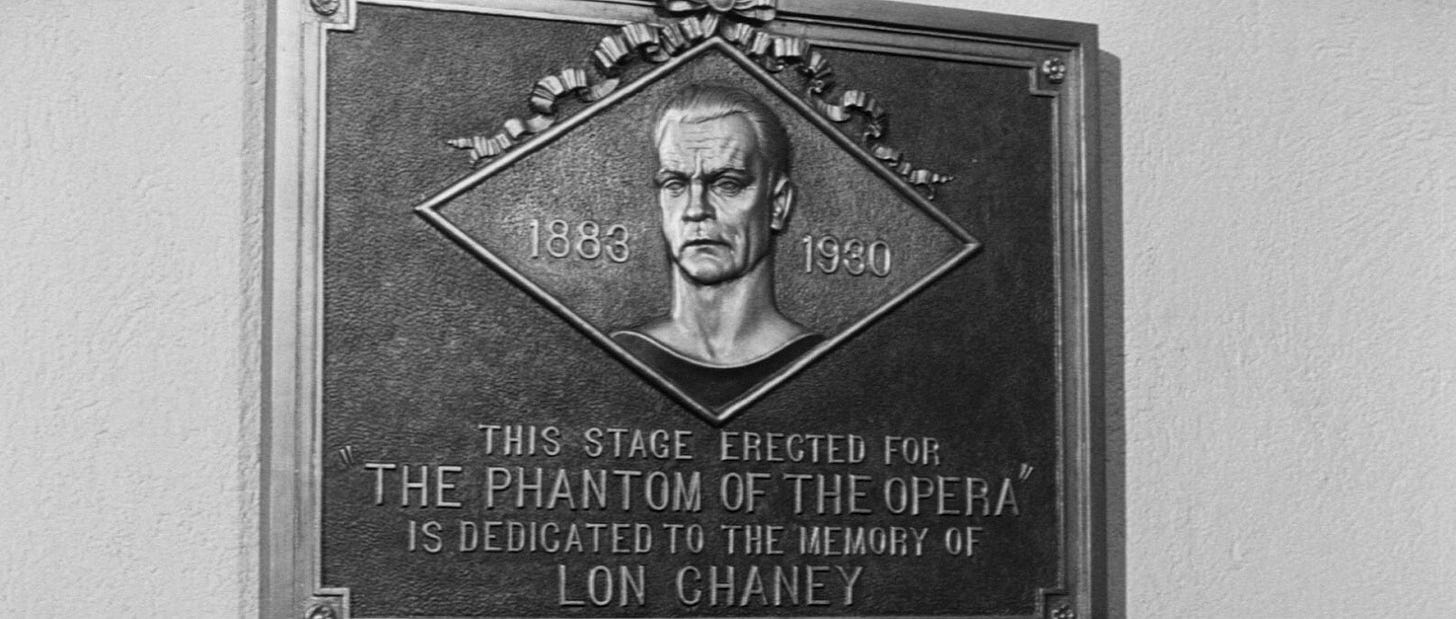

[Above: The Lon Chaney memorial plaque that the film alleges went up in 1930…except this isn’t the actual plaque. Plus, the real one didn’t go up on the Phantom Stage until December 17, 1940.]

Now, don’t get me wrong; it’s still a good film, and Cagney—at 58, really too old to play Chaney, who died at 47—is so great in it that most of us forget about his age. And I certainly think the film helped to keep Chaney’s reputation alive for many years after its release, which is a cool thing.

The origins of the film are interesting, too. According to Michael F. Blake—Chaney’s diligent biographer—the initial treatment was written by Ralph Wheelwright. Wheelwright had been in publicity at MGM back in the 1920s, which—of course—was Chaney’s studio at the time.

“He had worked with Chaney and kept all these notebooks,” screenwriter Robert Wright Campbell told W.C. Stroby later. “That was the basis for the story.”

By 1956, Wheelwright was busy with THESE WILDER YEARS, which starred Cagney. Wheelwright spoke to the actor about his Chaney project. Cagney was certainly interested.

“In doing the life story of such a great screen artist as Lon Chaney,” Cagney wrote years later in his autobiography, CAGNEY BY CAGNEY, “it belabors the obvious to say that I found it a challenge.”

Universal-International secured the rights to Chaney’s story from Lon, Jr. through his agent, Lester Salkow. Chaney, Jr. was embittered by the process—he later claimed to have written a script himself, but said that his materials were ignored in favor of studio screenwriters. [1]

“Lon Chaney, Jr. had nothing to do with it,” Campbell said later. “There were no consultations, no conferences, no discussions, no nothing. It may well be, for all I know, [producer] Bob Arthur may have had discussions with him, but I was never asked to get into it. I knew Lon from around the lot…”

Joseph Pevney, the eventual director, had a similar tale to tell.

“I never had any personal contact with the Chaney family,” he said later, “and none of them ever came to visit the set.”

[Above: Screenwriter R. Wright Campbell. Campbell started in pictures for Roger Corman, and reluctantly took up some acting as well. He’s pictured here in Corman’s FIVE GUNS WEST (1955). He said that the Chaney family provided no input for his script.]

In any case—as Campbell admitted—the etiquette of the time required sanitizing certain elements of Chaney’s life.

“[I]n those days the so-called harsh—well, the more candid, let’s put it that way—biographies that are done today were not possible,” he recounted.

Cagney, who knew and liked Lon, Jr.—they had worked together in A LION IS IN THE STREETS (1953), and Cagney described him as a “talented and very nice gentleman”—concurred.

“The Chaney family was a fascinating one,” Cagney wrote, “and in preparing MAN OF A THOUSAND FACES for shooting we came across several stories that for one reason or another we felt constrained from using.”

The most famous of these is of Lon, Jr. finally tracking down his real mother, Cleva Creighton.

As Cagney told it, Lon, Jr.—born Creighton Tull Chaney out of wedlock on February 10, 1906 (the day after a full moon)—was deserted by his mother. In fact, his father had told him that his mother was dead. When Creighton discovered that wasn’t true, he went to find her.

Heading to what Cagney describes as “a remote ranch somewhere out on the desert,” Creighton, “knocked, and a woman came to the door.”

“Yes?” she asked.

“Hello,” Cagney reported Creighton as saying. “My name is Creighton Chaney, and I’m looking for Mrs. Cleva Fletcher.” [2]

“What’s the name?”

“Cleva—Cleva Fletcher.”

“Oh, I’m sorry,” the woman allegedly replied. “No one here by that name.”

Cagney followed up with the gut punch:

“Then, directed to the woman, came a voice from inside the house: ‘Who is it, Cleva?’”

“This infinitely sad story we were unable to use,” Cagney explained. “The agonizing pathos of it—a desperately needed mother talking to a son she wanted no part of—the story seemed both crueler and larger than life itself.”

In fact, Cagney claimed to have only shared the story in his autobiography because, “the son, Lon Chaney, Jr., has gone…” [3]

[Above: Dorothy Malone as Cleva and James Cagney as Lon. The film accurately depicts the tension between them—a tension that ended their marriage—but takes great liberties with what happened after their divorce. Malone was given the part on Cagney’s recommendation, by the way.]

After Campbell turned in his draft, Ivan Goff and Ben Roberts (both screenwriters on Cagney’s 1949 gangster classic WHITE HEAT) gave the script another go. Cagney himself contracted to play the part at $75,000—a bit more than $855,000 at this writing—plus a percentage of the box office. [4] By November 7, 1956, the cameras were ready to roll…fittingly, on Universal’s famous PHANTOM OF THE OPERA stage. Director Joseph Pevney claimed that he was promised TAMMY AND THE BACHELOR with Debbie Reynolds, Walter Brennan, and Leslie Neilson if he did the Chaney film.

Also interesting is the fact that producer Irving Thalberg’s widow—actress Norma Shearer—was allowed to choose the actor who portrayed her husband in the film. She picked the unknown Robert Evans, and—according to Blake—Shearer “coached him to look and sound exactly like Thalberg.”

Moreover, permissions were sought from—and granted by—Chaney’s siblings (John, George, and Carrie), and Chaney’s detested ex-wife, Cleva.

So…what did Cagney, Pevney, Campbell, Arthur, and the rest achieve?

Well, I popped MAN OF A THOUSAND FACES into a Blue-Ray player about a week before writing this, and here are my observations…

To begin with, the plaque under the opening titles isn’t the actual Lon Chaney memorial plaque. Plus, it didn’t go up in 1930. The real plaque went up in 1940…according to historian Greg Mank, on December 17 (I believe him; it looks like it says December 17 in the picture below). And Lon, Jr.—in full MAN MADE MONSTER makeup—was there, along with 36-year-old Patsy Ruth Miller, his dad’s co-star in THE HUNCHBACK OF NORE DAME (1923).

[Above: The actual Lon Chaney plaque, which was dedicated on the Phantom Stage, December 17, 1940. Surviving members of the stage crew from Chaney’s 1925 classic join actress Patsy Ruth Miller and Lon Chaney, Jr. Note Chaney’s MAN MADE MONSTER makeup and costume.]

It’s interesting in the film that they have young Lon physically fighting to defend his deaf parents. This could actually be truthful, though Michael F. Blake doesn’t mention this. Still, Suzanne Gargiulo—another intrepid Chaney biographer—states, “Chaney had to deal with a lot of harsh comments and ignorance growing up.”

Cleva is a blonde in the movie. She was not in real life. Also, in the movie, she is the less successful act. This was not true. Her looks and voice gave her the edge early in their careers, which often made Lon jealous.

They make a big deal out of Cleva meeting Lon’s parents and discovering that they’re deaf. This is not truthful—according to Blake, she knew well beforehand.

Cleva and Lon, understandably, are already married when they discover her pregnancy in the film. This was not the case in real life. They were married three months after Creighton’s birth.

The film does get Lon’s love of the outdoors correct, particularly the ice fishing.

They got Lon’s brothers and sister’s names right, too. Having them sign off on the project likely helped.

They have Cleva acting awfully cruel about possibly giving birth to a deaf baby—she talks about not wanting to have the child at all. According to Pevney, this was by design.

“Dorothy Malone…turned Cleva into a real bitch…” he said later. “[S]he was really the villain of the picture.”

In real life, Cleva told the story that Lon requested that she have an abortion. Interesting how they twisted that, if true…

Anyway, Clarence Locan—played by Jim Backus—was an actual publicist. Blake says he later became a lifelong Chaney friend. But Lon’s movie agents were actually Richard Willis and W.A. Inglis.

(Just a sidenote: Jane Greer is certainly more attractive than was Hazel Chaney! Or is that petty of me?)

The film has Creighton born in the hospital… So, if Lon, Jr.’s famous tale about his father breaking through that ice and dipping him in frozen waters to revive him was actually true, why didn’t they do that here? It’s a truly dramatic story.

Well, my research indicates that Lon, Jr. seems to have started to tell that whopper in 1965, a tale both Lon Ralph (Junior’s oldest son) and Stella Bush (Junior’s half-sister) told Blake was complete fiction. (In addition, I’ve checked weather reports in the area from that day, and they don’t jive with Junior’s story. Ah, well…)

(Another interesting sidenote, at least for me: the actor who plays R.H. Macy in MIRACLE ON 34TH STREET (1947)—Harry Antrim—plays the doctor who delivers Creighton! How cool! MIRACLE has always been one of my favorites.)

The film certainly doesn’t portray the poverty that Lon Jr. always claimed his family lived in early on until Lon’s career took off…Of course, Cagney playing the loving father is marvelous.

[Above: Cagney as Lon as a dancing clown. Cagney, who could dance wonderfully in real life, enjoyed shooting these scenes a great deal. Interestingly, the film portrays him as the more successful act of the two…when in actuality, Cleva was the bigger one at first, thanks to her looks and singing.]

They do hint that Cleva was cheating on Lon, which was true. However, they don’t really deal with the fact that she was a very successful singer and performer, though they do indeed show her singing.

In the film, Cleva seems to get work behind Lon’s back, though in real life, Lon very much knew that she was successful…and, as we’ve already noted, was jealous about it. The portrayal of that jealousy between Cleva and Lon is true, and pretty effective.

However, they misrepresent the argument that Cleva and Lon had that resulted in Cleva’s suicide attempt. In the film, he wants her to stop working to take care of Creighton. In real life, he wanted to move on with the Kolb and Dill company, and she didn’t.

In the film, one of Cleva’s possible paramours is alluded to as “Darrell.” In real life, her known boyfriends were bartenders Don A. Traeger and Charles Osmand.

As far as we know, Lon never got Cleva fired from a job (as he does in the film), though—as we’ve seen—he was unhappy with her success and the hours she spent away from Creighton.

Carl Hastings is the name given to Hazel’s ex-husband in the film. In actuality, his first name was Charles. There have been conflicting reports over the years regarding whether or not Hastings was actually handicapped, and if so, what—exactly—his disability consisted of. But both Blake and Gargiulo state that Hastings was legless.

Did a jealous Cleva actually confront Hazel as in the film? There is no record of this that I can find, but you never know.

Cleva’s suicide attempt is handled a little bit over-dramatically. She didn’t run out on the stage and drink the poison. But she did drink it in the wings where Lon could see her.

I don’t know if it’s true that Lon found Cleva’s letters to her paramours at the police station directly after her suicide attempt. But Chaney did indeed find letters from Cleva to her extra-marital lovers. One to Traeger was entered as evidence in Lon’s divorce petition.

“When Lon found the letter,” Blake explained, “he showed it to Cleva who admitted that she had been in frequent correspondence with Traeger. She also said that she loved him, that he was going to send her money and that she had no further use for Chaney.”

[Above: The real Cleva Creighton Chaney. MAN OF A THOUSAND FACES takes many liberties with her story. When asked later by her grand son Lon Ralph how true to life the film was, she pronounced it to be “fairly accurate.” It really wasn’t.]

They do get it right why Kolb and Dill let Chaney go—scandal! The film also gets it right that he ended up going in the moving pictures as a result. [5]

Lon’s determination in the film that his son never hears from Cleva again is true. But he was not granted a divorce immediately…that took a year. And Creighton was never declared a ward of the court.

The Gert character (Marjorie Rambeau)—who serves as a mentor to Lon in the film when he starts in pictures—is really cool. But according to Blake, she’s fictional.

[Above: The character of Gert (Marjorie Rambeau) takes an interest in Chaney’s career and mentors him. Gert did not exist in real life.]

The introduction of the famous make up kit is handled well in the film. Did Cagney get good at applying his own make up? Not likely, but careful editing makes it seem so.

That said, the recreation of THE MIRACLE MAN (1919) seems a little bit phony, especially that foot twisting.

The “Lon Chaney, Man of Mystery” idea—voiced by the Locan character—is interesting, because that’s exactly what Lon wanted to be. (“Between pictures, there is no Lon Chaney,” he’d famously claim.)

Of course, the Big Pine cabin existed. And they do get it right that Lon told Creighton his mom was dead. Plus, Creighton did indeed “speak” sign.

They accurately present Hazel and Lon as mutual advocates. And they have it right that Chaney would try to portray “the soul of a man that God made different”; that was his thing.

[TOP: The real Lon and Hazel Chaney. They were a genuine team, and Hazel’s shrewd business sense helped them to live the life they desired. BOTTOM: Cagney and Jane Greer play well off of each other, making the Chaneys people the viewer cares about.]

The Westmore make ups (HUNCHBACK, PHANTOM) are indeed far inferior to Chaney’s. And we’ve got a doctor character weighing in, warning Chaney about how unhealthy his costume is. In real life, this was about the time Chaney met John Jeske. Jeske was Chaney’s friend, chauffer, assistant (he helped Chaney get in the Hunchback costume on the sly)…and Creighton’s nemesis (see CHANEY’S BABY). There is no mention of the real Jeske in the film, though he figured prominently in Chaney’s life.

They actually have Cleva showing up on the set HUNCHBACK. This is obviously an invention, and one of the biggest misconceptions the film perpetrates. Plus, they’ve softened her character. “She wanted to see your son…” This is why many people believe that Creighton and Cleva were reunited while Lon was still alive, a story that even Gargiulo considers to be possible.

But that’s not what Cleva herself said happened in real life.

In actuality, Cleva told reporter Adela Rogers St. Johns shortly after Lon’s death that she’d seen Creighton only once since 1914—as an adult, through a window. And Creighton didn’t see her at all. (Where, when, and how is still a mystery.)

“I figured the boy was better off with him,” Cleva said. “Only I thought Lon might let me see him, but he never answered my letters, and then I heard he was married again.”

St. Johns—who, in life, was friendly with Chaney—was saddened by the story.

“I always got the impression that the boy never quite forgave his father when after Lon was dead, young Creighton—known professionally as Lon, Jr.—found out about his own mother and went to see her,” St. Johns wrote in 1950. “It also seemed to me he held it against his stepmother, who was always very kind to him, that Lon Chaney had left her outright every penny of his fortune to do with as she pleased.”

[Above: The character of Cleva is softened in the second part of the film, where she is presented as a mother yearning for her son. In real life, she basically gave up on seeing Creighton, figuring that the boy was better off with his father.]

In the film, they have Hazel warn Lon that when Creighton finds out that his mother is alive, he will hate his father for it…which partially came true. But in reality, Hazel seems to have been complicit in Lon’s lie. (For more detail on this story, click here.)

Now, we have a scene with Creighton trying to make himself up…and Lon, trying gently to talk him out of acting. Certainly, this is not the way it was in real life. Lon was a lot harsher about keeping Creighton out of The Biz.

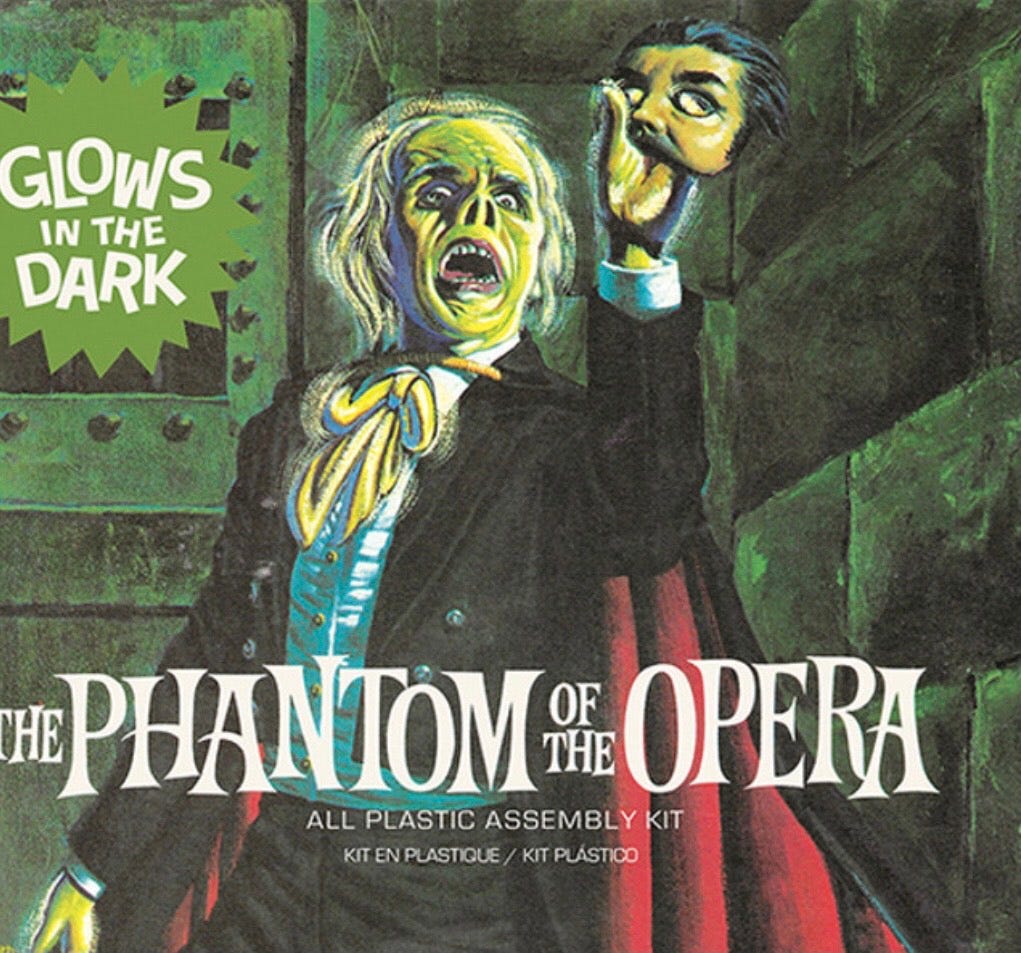

May I say that the PHANTOM scene recreations are terrible? The actress playing the Mary Philbin character—an uncredited Nancy Kilgas—is blonde, which is not accurate. It’s interesting to see that this Phantom makeup—supervised by Bud Westmore—was the inspiration for the classic Aurora Phantom model. It’s nowhere near the Chaney version. (For more on Bud Westmore, click here.)

[Above: As bad as Bud Westmore’s monster makeup for MAN OF A THOUSAND FACES was, it still seems to have inspired the look of the famous Aurora Phantom model kit (pictured here in an updated version by Atlantis).]

Were Chaney’s negotiations with Irving Thalberg that trusting? The film has Chaney basically throwing all of his financial interests in Thalberg’s hands. But the Chaneys—particularly Hazel—were shrewd about money. As such, this scene rings false to me.

Oh, and the scene with Cleva showing up at the Chaney household is one-hundred percent false. I mean, c’mon…Hazel and Cleva throwing in together against Lon? A total fabrication. Again, this is where people get mixed up—including some of Chaney’s descendants—about exactly what happened with Cleva. I believe it to be all thanks to this film! In real life, Cleva and Hazel did not bond.

They are correct, however, that Cleva worked as a cook. This was in Oxnard, CA, where she worked in beet fields and whipped up meals for fifty hands. Prior to this, she had lived in Utah. But the scene with Creighton encountering Cleva outside of the Chaney home is absolutely untrue.

Then, too, the scene where Creighton confronts his dad about the lie regarding the death of Cleva never happened. (For Creighton, it was a shame that it didn’t; he was robbed of the opportunity of expressing his justified anger to his father.) The film softens Cleva’s culpability in this entire incident. I can understand that from a dramatic viewpoint, but it’s not what happened.

Having Hazel be the one who reunited Cleva with Creighton is also false. Hazel never did this. And that’s one of the reasons why Chaney, Jr. went after her so hard after Lon’s death for a financial settlement. He thought she was as guilty as his father for withholding the truth.

In the film, Hazel seems to indicate that Lon’s love for Creighton got between the two of them. But in reality, that never happened. Lon loved Hazel almost unconditionally.

Chaney’s cough starting is handled pretty well. But this notion of Creighton living with Cleva? No, no, no, no, no.

And the idea that Lon would have made the first move to patch up things with Creighton? No, no, no, no, no! Lon was too stubborn for that.

(Is it too late to say that casting Roger Smith as Creighton was a bad idea?)

Sound pictures…Thalberg easily selling Lon on the idea… Again, not true. MGM certainly wanted him to speak, but Lon was very resistant to doing so.

Thalberg thinking Lon is going to be bigger than ever in Talkies? That might be true, and is pretty cool. Chaney probably would’ve launched his career anew, as the remake of THE UNHOLY THREE (1930) attests.

And Thalberg suggesting THE UNHOLY THREE remake…is that true? Yes, that appears to have been the case.

[Above: Cagney with Robert Evans as Irving Thalberg. The characters are portrayed as friends. They actually had a great deal of respect for each other, and Thalberg was an honorary pallbearer at Lon’s funeral.]

But…Chaney’s Mother Murgatroyd characterization—that he’d entertained Creighton with as a kid—as the basis for the UNHOLY sound remake character? Well, that strikes me as fiction.

Now, Clarence is going to see Cleva and Creighton at her house because Lon is sick? Bigtime fiction. No way did this happen.

And there’s no mention of Chaney planning to do the sound version of DRACULA. If that was actually in play, wouldn’t they have said something about it? (For more on that story, click here.)

This fishing scene to show the bonding between Lon and Creighton, where he apologizes about the mother thing, is a complete invention. And then they bring fish in for Hazel to cook. And then Lon has his final attack right then. SO not true.

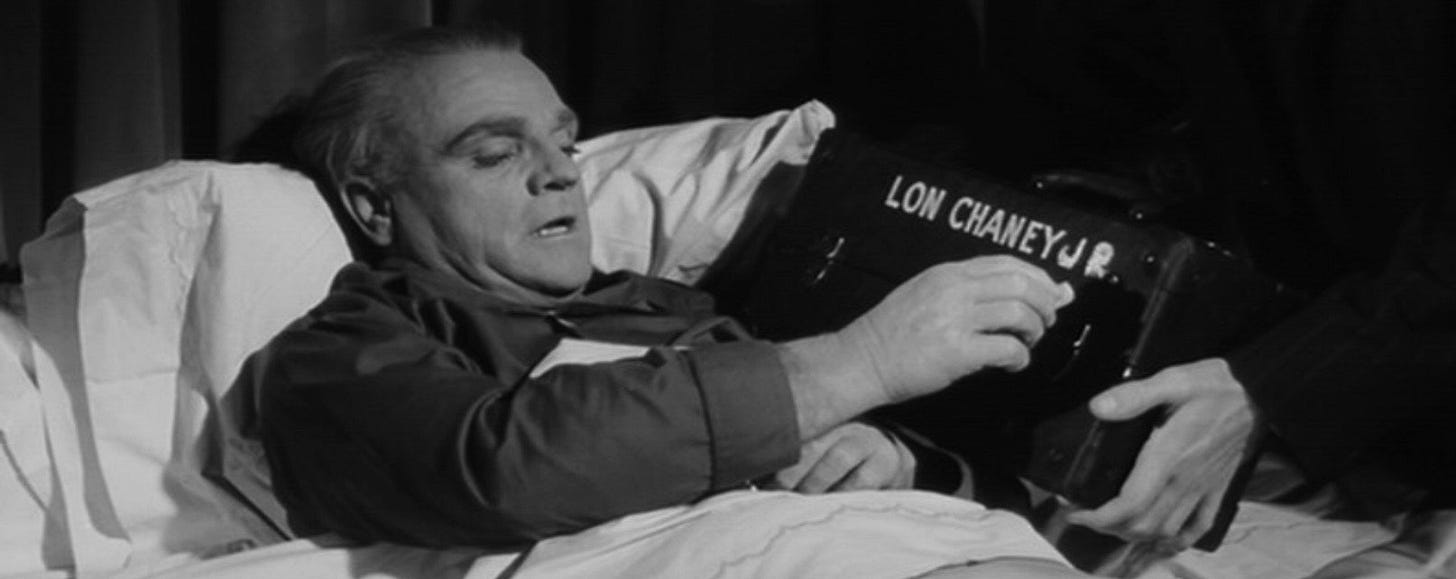

So, they have Lon dying at the cabin. (Lon actually died in St. Vincent’s Hospital in Los Angeles, as did Hazel on October 31, 1933.) Lon has them bring him his makeup box. He writes “JR” next to his name, but we know this is complete fantasy. It’s a beautiful ending, but nowhere near reality. In my opinion, it’s the biggest lie in the film.

[Above: The biggest lie in the film. The dying Lon—now mute—adds “JR” to his name on his makeup box. It’s a touching scene…and complete fiction. Lon wanted Creighton nowhere near the acting Biz.]

Of course, Lon “signs” that he loves everyone. Which I’m sure he did. And then he dies peacefully. Not like what happened in real life:

“Lon Chaney died at the age of 47 at 12:55 a.m., Tuesday, August 26, 1930, from a hemorrhage of the throat,” Blake stated.

Honestly, seeing MAN OF A THOUSAND FACES again after all of these years was good. It’s a nicely sentimental picture—well made, and well acted—that doesn’t have a lot to do with reality. If Monster Kids can see it with this in mind, they’ll be pleasantly entertained for a couple of hours…while knowing not to be fooled.

“MAN OF A THOUSAND FACES follows the facts more closely than some [biographies], although it hardly gives one a true portrait of Chaney,” Blake summarizes. “The most glaringly inaccurate scenes include Cleva’s not knowing that Lon’s parents were deaf; Lon’s being forced by the court to place his son in a foster school; Creighton’s learning the truth about his mother before Lon died; and Lon’s passing on his make-up case to his son…No other biography of a Hollywood star has influenced a larger group of young viewers.”

The film was a hit with most critics and at the box office. It made $2.4 million in 1957, the equivalent of $26 million at this writing. Plus, there was talk of Cagney and Celia Lovsky (Chaney’s mom in the film) getting Oscar nominations.

But one important viewer had a very different opinion.

“I remember when I came walking up the aisle from a screening,” Campbell told Stroby, “a studio screening and there just a few people there—I didn’t realize it but Lon Chaney, Jr. was sitting in the back of the room.”

As Campbell passed by, Lon Jr. provided his unvarnished opinion of the film:

“You really whitewashed the son of a bitch, didn’t you?!”

NOTES

[1] No Chaney, Jr. script has ever surfaced, though he was a good writer, as his surviving personal correspondence proves. See Blake, THE MAN BEHIND THE THOUSAND FACES, p. 283.

[2] As to the name “Fletcher”…Cleva had actually been remarried to William Bush, with whom she’d had a daughter, Stella. Cagney is mistaken here, or preserving Cleva’s actual identity. Cleva had died by the time Cagney wrote his autobiography, but Cagney might not have known this.

[3] True or not, it seems authentic to me, Creighton and Cleva did struggle a bit when reuniting after Lon’s death. She eventually allowed him to take care of her at times. But he rarely—if ever—mentioned her in public; he instead gave the press the impression that his stepmother, Hazel—whom he referred to as his “little Italian mother”—was actually his parent.

[4] What this percentage was seems to have been lost to history.

[5] Kolb is actually played by Clarance Kolb himself.

SOURCES

Blake, Michael F. A THOUSAND FACES: LON CHANEY’S UNIQUE ARTISTRY IN MOTION PICTURES. Lanham, MD: Vestal Press Inc., 1995. Ebook.

Blake, Michael F. LON CHANEY: THE MAN BEHIND THE THOUSAND FACES. Lanham, MD: The Vestal Press, 1990. Print.

Cagney, James. CAGNEY BY CAGNEY. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1976. Print.

Fleck, Bill. CHANEY’S AUDITION. Wurtsboro, NY: Just Pay the Ransom Publishing, 2024. Print.

Fleck, Bill. CHANEY’S BABY. Wurtsboro, NY: Just Pay the Ransom Publishing, 2021. Print.

Gargiulo, Suzanne. LON CHANEY’S SHADOW. Albany, GA: BearManor Media, 2009. Ebook.

“Hazel Bennett Hastings Chaney.” FIND A GRAVE. www.findagrave.com. Web.

Stroby, W.C. “Robert Campbell” (Interview). FILMFAX. May, 1990, pp. 64-71. Print.

NOTE: The pictures utilized here are intended for educational purposes only. I do not own the copyrights, and I don’t make money from this website.

Good story.

To be honest I’m not sure when I saw Man of a Thousand Faces for the first time, probably while I was in high school. But I do remember that I didn’t believe most of it. The film comes off too smarmy and that was and is my opinion of a lot of those biographical films of the time.

Wow. good read. Very interesting. I havent seen the movie in quite a long time; I must see it again with these new glasses. Thanks pal.